On Sunday and Monday, the Rhode Island Board of Education held its annual retreat to discuss, among many other topics, the high school graduation requirements. This was a hot topic because it includes using the NECAP as an up-or-down requirement for graduation: a student must get a 2 or more on both math and reading to graduate.

As anyone following this issue knows, there are are over 4,000 students who did not score a 2 on the last NECAP. This staggering number, representing about 40% of the students in the state, has caused considerable concern among students, their families, teachers, advocate groups, and politicians. In addition to numerous protest rallies, the city council and mayor of Providence have officially voiced doubts about this use of the NECAP and the General Assembly passed a resolution asking the Board of Education to reconsider its graduation policies.

In the midst of this mounting pressure, the Board announced plans to discuss the test related graduation requirements at its annual retreat, which it scheduled in the pleasant, and secluded, location of Alton Jones.

Initially, the Board intended to conduct this retreat in private until the ACLU and other concerned parties (including me) pointed out that this discussion amounted to conducting Board business and therefore fell under the open meetings law. The Board did not see it that way, but a judge did, and the retreat was held, open to the public, at Rhode Island College.

The retreat was keynoted by Aims McGuinness, an outside expert, who said a few interesting things to the Board. First, he emphasized the unique nature of their responsibility—creating policy that maximizes the effectiveness of the educational pipeline that moves students from earliest pre-kindergarten edu-care to successful entry into the labor market. Despite the heavy labor market emphasis, I appreciated his spelling out the big picture–and his warning that, if the Board doesn’t keep the big picture in mind, it will “get lost in the weeds.”

Aims had less to say about the elementary/secondary section of the pipeline than he did about the postsecondary section. In our colleges and university, too many students don’t make it through, degrees are not granted in economically strategic areas, and affordability for students is low. Interestingly, he DID NOT say our biggest problem was the number of unqualified high school graduates showing up on employer’s doorsteps.

Another big point Aims made is that, while many of our average numbers are good (numbers graduating, educational attainment of graduates, etc.), when you begin to disaggregate these numbers by income, race, or family education, you see “about six Rhode Islands”, areas defined by large inequalities in wealth and opportunity. These inequalities, Aims stated, will drag the state backwards as it tries to build an education pipeline that feeds an improving economy. During his presentation, he came back to this point repeatedly: inequality is a ball and chain that will drag this state down.

The final point from Aims was the need for a system—educational and economic–that promotes innovation. This makes sense to me—innovations become established ways of doing things and lose their effectiveness, so we need a system that continually promotes innovation. This is a pretty thoroughgoing project—you can’t develop innovative students in a system with conventional teaching, and you can’t promote innovative teaching with conventional administrations operating under conventional policies.

My big takeaway? The Board of Education needs to develop policies that create an educational pipeline that promotes equality and innovation. I was pretty happy with the way Aims set the stage.

But then reality struck—the Department of Education began to go to work to convince the Board that the NECAP graduation requirement was crucial to the success of education reform in Rhode Island.

A big part of their argument was that it worked in Massachusetts, so it will work here. In order to make this argument, they brought in Don Driscoll, the former Commissioner of Education in Massachusetts who implemented the 1993 Education Reform Act. That legislation resulted from the state losing a lawsuit that required them to put in an adequate and equitable public education funding system. You might recall Rhode Island lost a similar lawsuit (under Judge Needham) but then it won it (under Judge Lederberg). So Rhode Island was never required to adequately or equitably fund its education system.

But Massachusetts was. The new law required that, after a seven-year phase-in, every local school district spend at least a state-mandated, minimum amount per pupil, for which the law provided much of the funding. This minimum “foundation budget,” is supposed to cover the costs of adequately educating different categories of students (regular, limited English proficient, special education, low income, etc.), and consequently varies by district.

In addition to creating a testing requirement for graduation, Massachusetts provided a seven-year ramp-up in state funding to beef-up poor districts and their schools. I emphasize all this because Driscoll barely mentioned it and I think it probably has a lot to do with whether Rhode Island will meet with the same success Driscoll proudly described achieving in his state.

So, a seven-year ramp-up of state funding and a ten-year period of professional development preceded the implementation of the test requirement, but Driscoll treated these as unimportant, saying nothing much happened until the test requirement kicked in and people started to focus.

In my arrogance, I’d like to contradict Driscoll on the point that nothing was happening in Massachusetts before the testing requirement kicked in; NAEP testing shows that educational attainment in Massachusetts was on the rise even before the state kicked in significant new money. Some myths—such as the test is the only thing that matters–just don’t stand up to the evidence.

The other point that got swept under the rug by Driscoll was how stubborn gaps in educational inequality are. The following excerpts are from Twenty Years After Education Reform: Choosing a Path Forward to Equity and Excellence for All (French, Guisbond and Jehlen, with Shapiro, June 2013):

- •Massachusetts’ progress in narrowing gaps has been outpaced by most other states in the nation, leaving Massachusetts with some of the widest White/Hispanic gaps in the nation. Massachusetts now ranks near the bottom of all states in terms of our White/Hispanic gap, ranging from 38 achievement gaps in math and reading at the 4

- In terms of the White/Black achievement gap…The ranking of 23 gap in 4 Massachusetts with a ranking of 35 between Black and White students at both the 4th and and 8th grades.

- The state’s Hispanic graduation rate ranks 39th out of and is lower than the national average. This places Massachusetts 31st of 49 states for the gap between black and white student graduation rates (with 1st meaning the gap is the smallest of 47 states for the size of the gap between Hispanic and White student graduation rates.

- The NAEP test score gap between free/reduced lunch and full-paying students in Massachusetts remained static across both grades and disciplines, while other states have made progress in reducing this gap. As a result of this pattern, Massachusetts’ ranking has fallen over years so that the state is now ranked from 27 score gap by income.

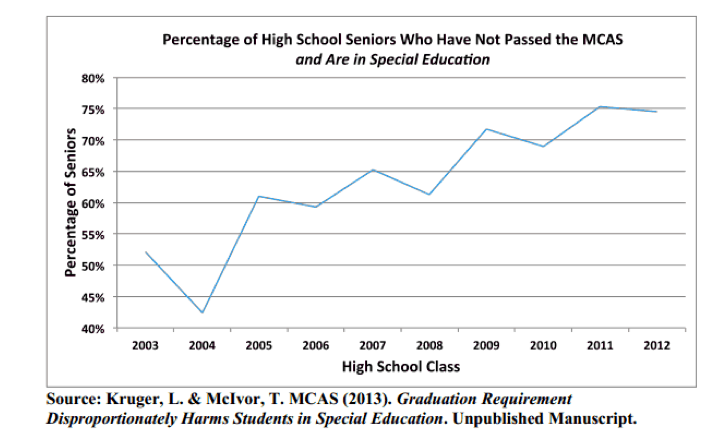

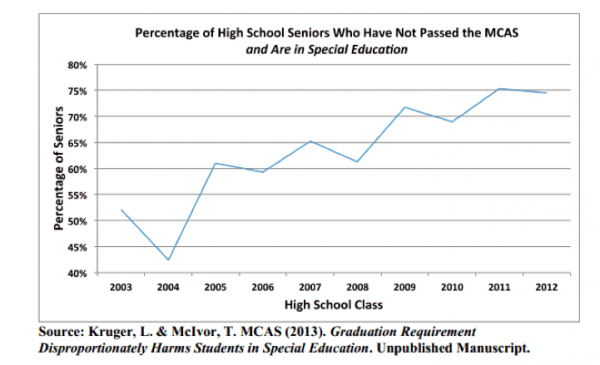

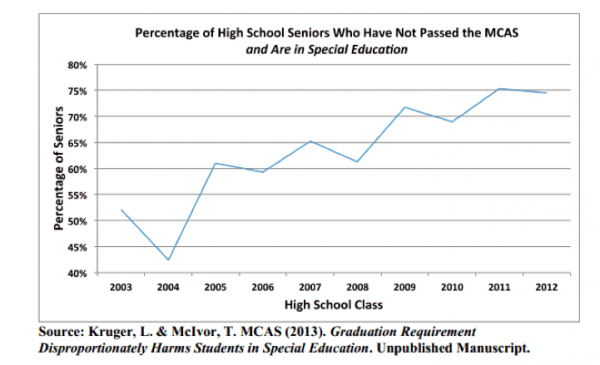

- And, for students in Special Education, this graph speaks for itself:

What is interesting about these facts—besides that they were never mentioned—is that they should give pause to a state Board just charged with promoting equity as a top priority. In fact, a Board truly concerned with equity would see these indicators as huge red flags standing in the way of adopting the NECAP as a graduation requirement.

Finally, I am compelled to mention another difference between Rhode Island and Massachusetts that is relevant to expecting the same level of success in Rhode Island as Massachusetts experienced.

Massachusetts has a population that is significantly wealthier and more educated that Rhode Island. While I do not subscribe to the idea that wealth and education pre-determine educational attainment, it would be blindly foolish not to recognize that these factors tilt the playing field: wealth tends to provide opportunities and education tends to replicate the values and skills that produce educational attainment.

Depending on the indicators of wealth and education you choose, a plausible argument can be made that Massachusetts is, on average, the wealthiest and best educated state in the country: no such argument can be made in Rhode Island. But in RIDE, where teachers are the only factor that matter for educational quality, wealth and education are not considered when making policy.

For me, the highlight of the day was a skyped in interview with Tony Wagner, a Harvard professor with lots of experience educating urban students. Tony said a lot of important things, but the heart of what he said was that if we want to be successful with urban students and close the achievement gaps that are dragging us down, we need to figure out the problem of motivating students.

His answer, in simplified form, is to build on what students know and are interested in, using this as the beginning point for teaching. In Tony’s approach, students would work with teachers, who would function as much as mentors as advisors, to educate themselves in the areas they are interested in. Tony advocated that students undergo continual evaluation of their work and that this evaluation cumulate in an electronic portfolio.

While this abbreviated description does no justice to the power of Tony’s approach, it almost didn’t matter because the Board showed little interest in the only presentation that addressed the issue of inequality, closing performance gaps, and education that promotes innovation.

Instead, it showed an intense interest in the speakers who affirmed the valued of using the NECAP as a graduation requirement. These speakers included the President of Measured Progress, a contractor that works for RIDE. You can be sure these guys will tell you what you want to hear.

On Monday, one member of the Board, a swing vote, was reported in the Journal as saying the presentation had convinced her that using the NECAP was the way to go. Luckily, I was there to witness how policy gets made. Otherwise, no one would know they are deep in the weeds.

As every living Democratic POTUS addresses the nation from the Lincoln Memorial on the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington and the “I have a dream” speech, Rhode Islanders will be honoring the occasion by meeting at the Martin Luther King Jr. bridge on Finance Way in Providence for a “re-dedication” by Bernard Lafayette, founder of the Institute for the Study and Practice of Non-Violence who worked with King.

As every living Democratic POTUS addresses the nation from the Lincoln Memorial on the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington and the “I have a dream” speech, Rhode Islanders will be honoring the occasion by meeting at the Martin Luther King Jr. bridge on Finance Way in Providence for a “re-dedication” by Bernard Lafayette, founder of the Institute for the Study and Practice of Non-Violence who worked with King.