As someone who makes $10/hour at a part-time 1099 job, and who was recently unemployed, you would expect that I’d be pretty enthusiastic about the potential to raise the minimum wage. Although my current pay is above the paltry $7.25/hour federal minimum, it’s well below what most consider to be a living wage in the U.S., and I would likely be able to push my boss to pay me more if the minimum became $9.

Folks who are fighting for an increased minimum wage are truly my type of people–they’re people who see an absurd gap in wealth in this country, and want to stop that. But I think minimum wages are, in general, a poor way to fix the wealth gap; and local minimum wages are an especially bad way to go about it. We should understand that pushing local minimum wages is not only a lousy stopgap, but more truthfully should be described as a distraction. They’re a Kabuki Theatre approach to politics in which an ineffective and poorly planned “liberal” solution is trotted out to be assaulted by a rabid and selfish rightwing, only to keep people from thinking of more complete answers in their own non-partisan terms.

When the Great Depression happened, and people were literally breaking down the doors of banks to get the money they intended to use to buy groceries or pay their rent with, Keynesianism came to the forefront as a solution to the problem. And as a short-term stop gap in emergency situations, Keynesianism is a great idea. The urge to save one’s money can be corrosive in a crisis, said Keynes, because if everyone does it at once, what makes sense for the individual will not make sense for the group–the economy will stall. There’s nothing to say that using Keynes’ ideas in crises is a bad idea.

The problem is, we’ve now substituted Keynesianism for a more thoroughgoing approach to wealth disparities, and with even the most “progressive” of the DINO-style Democrapublicans not wanting to do much for the poor, we’ve introduced Keynesianism into our activism as a substitute for a real discussion of the wealth gap. Keynesianism is often represented in our liberal minds as being like social programs that give back, but its strategy is more to be a monetary priming to get growth happening again. More often than not, actual day-to-day Keynesianism is implicated in projects liberals should hate. Have you ever heard that we should keep a subsidy to an oil project because it “builds jobs”? Or that we should tear through a neighborhood with a polluting highway to “grow the economy”? Keynesian projects tend to be top-down, and though small portions of the Keynesian picture on the fringes are things like food stamps and so forth, the biggest Keynesian project of all has always been our military bloat. It was WWII that brought us out of the Depression.

It doesn’t help that there’s a robust (and idiotic) Tea Party insisting that we should just leave everything the way it is, and so in classic knee-jerk style, we hear that our enemies don’t support something, and therefore it must be good. Liberals embrace Keynes because his philosophy says “do something.” And we should do something, just something different.

The problem with raising the minimum wage in general is that it does nothing to address the ratio of income between people, and even less so to affect the ratio of wealth (which is at an even greater gap). What it does instead is cause a temporary bubble of spending, and in that spending we’re all able to go about our business pretending that the same old inequalities aren’t as harsh as before. But that bubble quickly collapses in inflation, and the wages of the workers stagnate.

Another problem is that in many cases, raising the minimum wage means that people who are less likely to have jobs are the first not-hired by companies that are being selfish. The trade-off from this selfish behavior is that those who are hired do slightly better than they might have, but those who are unemployed do worse. I say that businesses are “being selfish” because that’s what they’re doing–owners make decisions based on what they think will make them money, rather than what’s right, but the result is that people who are marginalized in society sometimes can’t find work. The point here isn’t that we should let that selfishness reign supreme. We should regulate it. But we should make sure that the regulations we create work well. Left-leaning people should understand that businesses want to follow only the bare letter of the law while evading the spirit behind it entirely, and so when we approach the issue of stagnated wages, that should be part of our analysis. A Republican may say: “businesses are good at evading the law, so leave them alone.” I’m saying, “businesses are good at evading the law, so regulate them better.”

Local minimum wages are an even bigger problem than federal or state ones because their limited geographical scope means that employers have a reason to push jobs out of wherever the wages are high to somewhere else. This isn’t a unidimensional thing. A city like Providence, if it enacted a local minimum wage, might find that some sectors stay or even grow, while others try to leave. But again, the distribution of who stays and who leaves–and which workers are affected by that change–can be a very bad aspect of the law. Workers who make low wages, like me, are far more likely to not own cars, and be either transit riders or bicyclists. If some jobs decide to move to Cranston, or Johnston, or some other far flung place, it means either having to take a much longer commute by bus; the additional time, danger, and stress of a longer bike commuter into suburban or exurban territory; or simply buying a car. Whatever advantage in wage growth exists for those who do keep their new, farther-away jobs will be eaten by this lost time to family and friends, this lost health outcome in time sitting at the wheel or dealing with dangerous cars, and in the worst case, money lost on a car (about $10,000 a year average, with $6,000 year average for a used junker).

And the loss of jobs to cities–which being the progressive centers, will be the places with high local minimum wages–will be only the beginning. Because having our society push farther and farther into the exurbs is an actual physical cost to us as a whole. It increases pollution. It wreaks havoc on our road maintenance budget. It eats up farmland. And here I’ll sound a bit like a Republican again–one of the biggest problems is that all the supposed growth that’s happening is eaten up into waste and debt (private and public).

The idea that growth affects the relationship of poor people to rich is not an entirely crazy one. Many historians note that American politics has a growth-oriented spin to it compared to Europe due in large part to the unusual situation we have of having arrived on a continent with people dying around us from our diseases, and then being able to expand exponentially into “empty” territory. The population of France in 1800 was about 30 million, today it is 60 million. The population of the U.S. was 3 million then, and today is more like 300 million. When we instigate growth, the importance of wages versus capital in an economy can change as a result, putting workers in more control, according to Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century. The ability to grow and expand outward in the United States meant that our labor movement grew in a completely different way, and focused on very different things (and this was also deeply affected by that growth’s relationship to slavery, expansion against Native Americans and Mexicans, and so forth). We can’t expect another hundred-fold growth to happen, even though that growth is represented as “just” 1 or 2% a year. We have to recognize that our resources are limited, and start to have serious conversations about how those resources and power are distributed.

I started this essay saying that of course I do think that the wealth gap is a serious problem we should address, and my hope is that people who may otherwise have regarded my tirade against minimum wages as regressive and reactionary have slogged through this long enough to get to this part. Because we certainly should address this problem smartly. The high point of the 20th Century had many things wrong with it, but one thing that was right-smack-on about our policy during those golden decades was that we had good macroeconomic policies that dealt with the ratio between rich and poor. We taxed earnings higher than $200,000 (then worth quite a bit more than even today) at a 90% rate. We had a strong estate tax. We set up the society such that there were not only minimums, but maximums as well. And that’s absolutely vital, because money is a relational thing which has no real value outside of our mental constructions about it, so when we say that everyone has to have at least $9 an hour, the value of that statement is measured against whether no one can have more than $x per hour as well. With the wealth gap much wider than the income gap, measures to remove intergenerational transferral of wealth from rich parent to rich child should be undertaken as well, because those are the things that make it possible to level the playing field and fund important social services like public schools or universal healthcare.

But by all means, the left should abandon this nonsense from Keynes. Keynes was a smarter guy than I’ll ever be, and his ideas about economics have many legitimate uses. But when we adopt Keynesian growth as an argument for things like this, we mask the effects of inequality without resolving them. And we create more problems on top of that. We’re risking a future in which we come up hard against the pending costs in monetary debt and physical real-world resources due to constantly reinvesting in bubbles. A local minimum wage is an especially bad thing, because while a state minimum wage does little to address our real problems, a local one does that plus chasing economic activity out of cities.

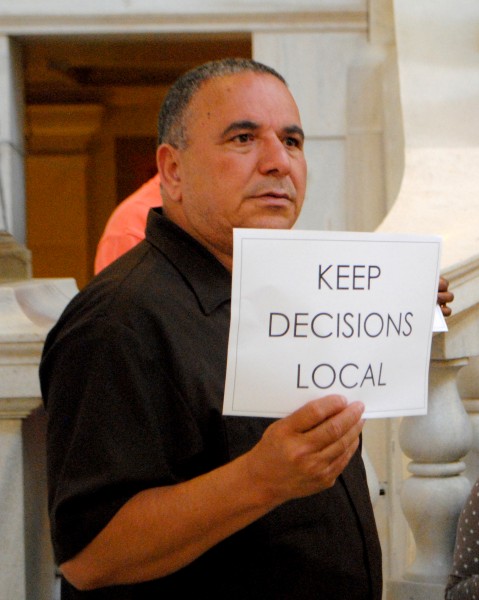

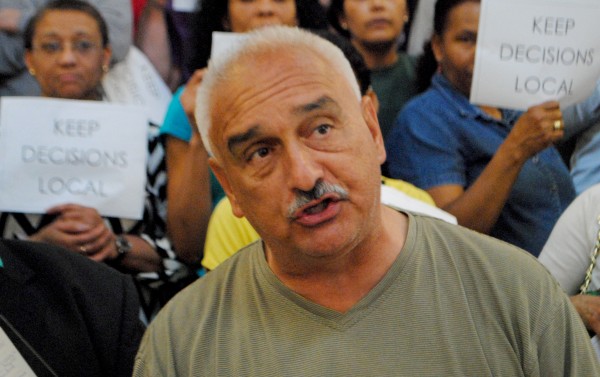

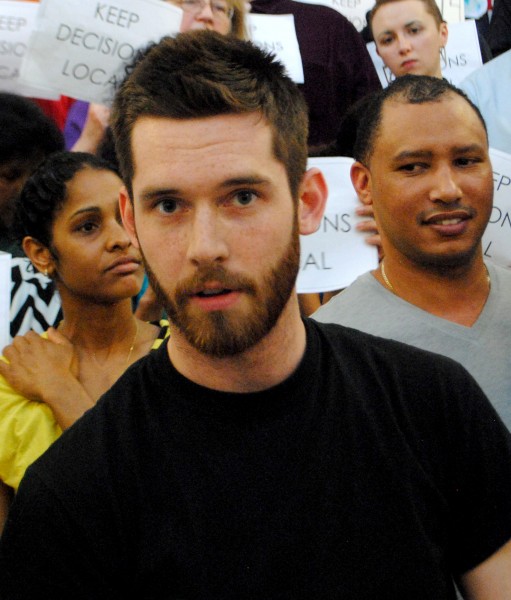

More than 125 people turned out a rally at the State House against the General Assembly’s proposed state ban on cities and municipalities setting their own minimum wage standards. Citizens, workers and elected officials raised their collective voices to tell House Leadership that this legislative power grab will not be welcome in Rhode Island.

More than 125 people turned out a rally at the State House against the General Assembly’s proposed state ban on cities and municipalities setting their own minimum wage standards. Citizens, workers and elected officials raised their collective voices to tell House Leadership that this legislative power grab will not be welcome in Rhode Island.