As some of you may be aware, I very much disagree with the RI Progressive Democrats decision to push for a return to the way that car taxes were assessed in Providence. I previously had the ear of some of the mayoral campaigns, and have been attempting in my own small way to push them on this issue, but have found them to be unreceptive.

As I’ve attempted on my own blog to bring attention to this issue, it’s become clear to me that in order to win, there has to be a list of viable alternatives to lowering the car tax that accomplish the equity goals outlined by RIPDA without resorting to a subsidy for driving.

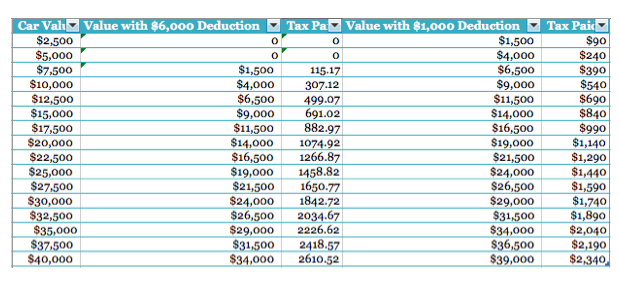

First, some background. The car tax in Providence is based on state DMV assessments of the value of one’s car. In the past, the state offered a $6,000 deduction for the value of one’s car, meaning that tax was only assessed on cars above that value. More recently, the deduction was withdrawn, and Providence residents currently enjoy only a $1,000 deduction. This also went alongside a small reduction in the percentage of taxation, overall. I made a spreadsheet that explains how this breaks down:

As RIPDA members point out, the change in the way that taxes are assessed results in people who own cheaper cars having to pay more tax than they did previously. Around the middle of the spectrum the change has little effect, and at the upper end people can expect to pay somewhat less tax. An important figure left out of this conversation is that 25% of Providence doesn’t drive at all and this group, much like the non-driving population of most places in the U.S., is overwhelmingly low income. Changing the way that this tax is assessed will not help those who do not drive. It’s also important to keep in mind that the tax on cars is not really intended as an income redistribution tax, although in other cases I would very much agree with having a progressive system of income redistribution. The purpose of a car tax is to have drivers pay the costs of driving, which even in the current system, they don’t.

The cost of driving is never fully allowed to touch drivers in the U.S., as opposed to in many countries that actually do take care to have better distribution of wealth, like the social democracies of Europe. Yet, when costs are assessed to drivers, it impacts whether and how much they choose to drive. For instance, people who work at jobs that offer an equal free parking or transit benefit are more likely to drive to work alone than those who get neither benefit, demonstrating that the existence of a free subsidy to driving even outweighs an equal subsidy to not do so. Forgiving even the small portion of costs that the car tax makes drivers pay ensures that more people will choose to drive in Providence.

Still, be damned whether this brushes over the 25% that are most likely to be poor! Be damned the environment! Some of you out there just want to know what’s in it for you if you’re hanging in that middle zone of people who can afford a car but hate paying the car taxes.

One option for supporters of reducing the car tax to consider is putting the money from the deduction to RIPTA. The first $6,000 of car value at 6% is equal to $360 per car. If 75% of Providence households continue to own just one car, that’s like $50 million in revenue for RIPTA, which could be targeted only to city bus service in lower income areas. This could mean better shelters, more frequent service, upgraded facilities, or other conveniences. RIPTA could offer a set number of free RIPTA cards to lower income families, or could put the money aside to help pay for the school-aged RIPTA cards it issues. With improved RIPTA service, it’s very possible that some households would choose to give up their cars, and so any assessment of this plan has to assume that there’s going to be multivariable math going on. However, this at least is a win-win situation: either people pay the fee to own a car, and help create better transit service, or they choose to give up their car, also reducing our transportation expenses.

A second option is to focus on bike infrastructure. Despite the visibility of white, upper-class people in spandex on fancy titanium bikes, studies consistently show that those who ride bikes for transportation are more likely to be lower income. Putting quality bike infrastructure in lower income neighborhoods would provide a low cost way for people to get exercise and transport themselves to-and-from work or school, and would really cut away from the need to have a car to transport children. There’s a real equity problem with the way that many cities allocate bike infrastructure, and putting a preference in place for low income neighborhoods to get the first and best of the pack would be a really equity gain.

One problem that exists with the car tax is that it comes as a sudden shock to some people, who may not expect it. I’ve been talking for some time about the need to have a parking tax in the city, and I think that one way we can lower the car tax while keeping the cost of driving the same or greater would be to take some part of the car tax and put it into a per-space tax on parking lots. This would help to incentivize development and infill, lowering the need to drive by reducing job and housing sprawl. It would allow the costs of driving to be paid more incrementally, in a way that’s predictable to users. It could help the city reduce property taxes, particularly on rental properties, which pay a higher tax and are more likely to house lower income people. A parking tax could really help put us on better footing.

For a lot of reasons, I’m not sure I would support using the funding for non-transportation uses. As I said, because drivers do not pay even close to the full amount of the costs their vehicles contribute to road construction and maintenance, there’s no way to wish away the expenses that exist in city government for these expenditures. This is part of the reason that lowering the car tax is so problematic in the first place: it may be that it helps to make driving cheaper for some in a temporary way, but as costs mount it also means that some other kind of tax has to go up, or that some other service has to suffer. So, while funding schools out of taxes on cars sounds morally sound to me, I’m not sure the costs would add up long-term. The city would need to take money from schools to pay for roads, and it might just end up being a wash. I also worry about what might happen politically to a city that funds schools through car charges. We should view a tax that puts the real costs of car ownership on the shoulders of drivers as a good thing, but if we find that important social goods in our society are funded by the continuation of more car ownership, that might give us a perverse reason to avoid fixing our transportation situation. This is, for instance, the conversation that already exists, where drivers accuse bicyclists or transit riders of “freeloading” on the system for not paying gas taxes, even though these users obviously pay generously from general tax funds for roads, and contribute a great deal less to the roads’ maintenance costs.

In any case, it may be defensible to try to ease the burdens of lower-middle class drivers, but we should structure any change in a way that helps to support the needs of non-drivers as well, and which helps to foster a better transportation system.

Reducing the car tax isn’t the way to do that.

Correction: The author acknowledges an error in the amount of revenue from this tax. While $360 is 6% of $6,000, there is still a $1,000 deductible for car value in place. This means the difference in tax is between the $1,000 deductible and a $6,000 one, not between a $6,000 deductible and zero. The difference in tax for a $6,000 car is $283. The revenue, assuming no change in driver behavior, is around $40 million, not $50 million.