There are several ways a parking tax could easily be implemented in Providence.

There are several ways a parking tax could easily be implemented in Providence.

In a previous post I introduced the concept of a parking tax for Providence. This post explores five such options for implementing and collecting parking taxes. Future posts will demonstrate how much revenue can be raised, how it could offset other city taxes and what social benefits will result.

A revenue tax on commercial lots

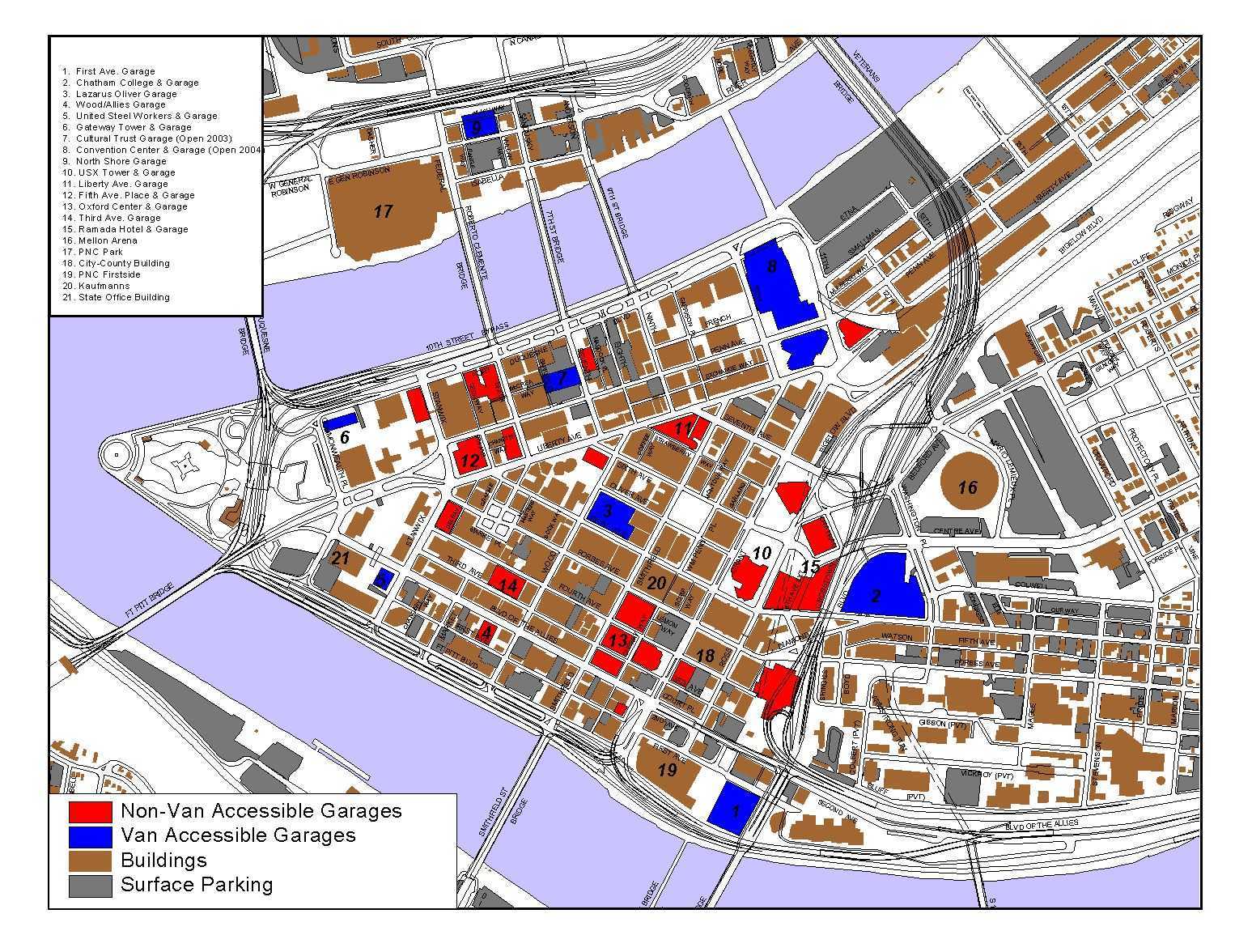

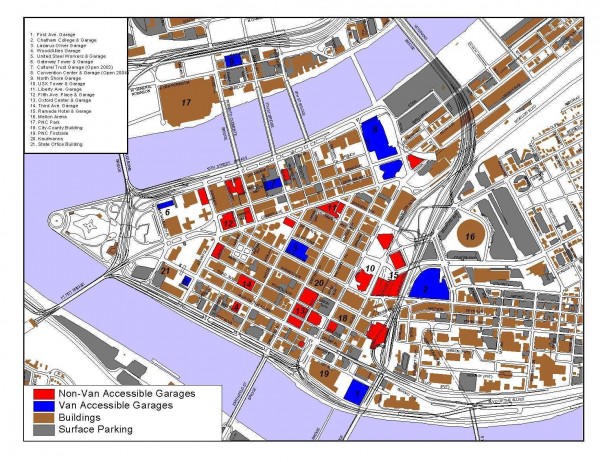

The easiest way to enact a parking tax would be to pass a tax on the revenue from commercial lots – that is, the ones that charge a fee to commuters in the downtown. This is the tax collection model in Pittsburgh, where lot owners are expected to keep receipts of the revenue they collect and pay a 40% tax on that revenue.

There’s a range of effects that could take place with this kind of tax. If demand for parking was really high–no one who already parked stopped parking–lot owners would be in a position to pass 100% of the tax on to customers. So, imagine for instance that your normal fee is $10/day. That fee would become $14/day.

If demand for parking was really low–everyone, say, decided that it was not worth it to park–then lot owners would have to eat the tax entirely themselves. Lot owners pay around $0.60 per spot per day in taxes, so paying a $4 a day tax would be left with a strong incentive to either sell or repurpose their land. Even if a healthy number of people still chose to park, lot owners might be incentivized to reduce the size of their lots in order to stop having to eat so much of the tax. This would reduce parking tax revenue (and parking supply) but would increase tax receipts from buildings (and more importantly, would mean that there’d be way more cool things to visit, places to live, and jobs to work at in the downtown).

The reality is that demand for parking would fall somewhere between these two extremes. Lot owners might feel some pressure to take on some of the tax as a profit loss, because at $0.60 or $0.70 a spot in property taxes, a $10/day fee minus x amount of additional parking tax would still leave them a healthy profit. There would probably be enough demand for parking that commuters would pay some of the tax themselves in higher fees, too.

The big thing to remember about a revenue tax is that if a parking spot were free in the city, the lot owner would pay no tax. If the spot were on the market, but didn’t “sell”, i.e., no one parked in it, it would also be tax-free.

A “per spot” tax on commercial lots

A tax on lots “per spot” could be applied to commercial lots. This varies from the revenue tax in that the city would decide a fee for each parking spot that did not depend on usage. In our 40% example, $4 would be the fee on a $10 parking spot, so perhaps the city would just say to lot owners, “if your spots are on the market, there’s a $4 tax. 100 spots is $400 a day tax, no matter who uses them.”

Lot owners in this scenario would face a slightly different situation, and I imagine this tax having a stronger effect on reducing lot size as well as a greater immediate effect on reducing the profitability of parking lots. For instance, if a lot owner has 20 spots open on a given day, that that’s an $80 loss. If it comes to 10 AM, and those spots aren’t full, he or she may give them away for $4 each, just to break even on the tax. A lot owner won’t accept that position for long, though. He or she will start to look at the bottom line and think about how to get rid of parking spots that are typically not full.

The other advantage to the “per spot” tax is that it’s much easier to account for. The city uses Google Maps, and counts, and issues a bill. In order to prevent fraud in revenue tax situations, cities often use some kind of a smart card, so that there’s an unchangeable paper trail. But none of that would be necessary for a per-spot tax.

Per spot taxes are favored by the Victoria Transportation Policy Institute, covered here on Streetsblog.

A “per spot” tax on all parking lots

A per spot tax also opens up the possibility of taxing all parking lots in the city, not just those that charge a value for their parking. I really think this is the best option, but I also realize that there are political difficulties to implementing it.

A disadvantage to only taxing commercial lots, whether in the “per spot” or “revenue” model is that it creates an arbitrage around the value of parking on free lots. An arbitrage is when something is selling for one price one place, and a different price in another. It’s the kind of thing that day traders take advantage of when they’re doing frivolous trades back and forth to make profits without creating things. Arbitrages can also be a legitimate tool in a marketplace, helping people to make sense of what the price of something is, if information is shared fairly. You don’t want to go out of your way to create one, though.

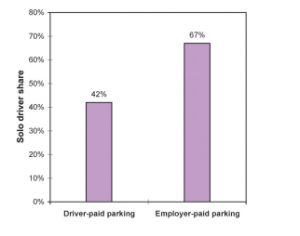

Imagine you’re the owner of a business. The cost of paving a flat parking lot might be very small to you, both in upkeep and taxes (property tax assessments would say that the lot wasn’t really worth anything). If you give your spots away to your workers for free, your workers are super excited. To them, this is a $14/day value, because their access to parking is solely through what they can buy from a commercial lot, and what is given away to them by an employer. But you, the employer, have a great deal more leverage. You’re not really giving your workers $14/day at all. You’re taking advantage of a tax loophole to turn a tiny investment into a huge benefit for your employees (and you). That might sound well and good if you’re the employee, but it circumnavigates the purpose of the parking tax, so the more we can do to stop that problem, the better.

A tax on free parking would tend to affect big box stores disproportionately, which in my opinion would be both fair in a market sense of the word (pay for what you use) and in a share-the-wealth way. A business like Home Depot is imposing a lot more cost on the city through all types of infrastructure than, say, Adler’s Hardware store on Wickenden. An African grocery store on Cranston Street in a bottom floor of a three story building is costing the city much less than a Stop & Shop. And you’ll notice, although there would be exceptions, that most of the smaller footprint businesses tend to be independently owned. It’s also the case that some Dunkin Donuts stores or other chain stores might get thrown into the mix. But for the most part, the tendency would be that large chain stores would have huge parking lots, and local businesses would have modest parking lots, or no parking at all.

Another really big advantage to a tax on big box lots is that, so long as the city allows it, big boxes may not necessarily object to having somewhat smaller lots. There was an absurd case of a municipality requiring so much parking that even Walmart asked for a variance to get out of the requirement. Parking requirements for big box stores is usually set to some imagined peak demand, usually Black Friday or Christmas Eve, and transportation advocates have even gone out on these days to take pictures and show how overabundant these parking supplies are even for that purpose. So big boxes would have a choice: pay a tax on parking that’s excessive to begin with, or lease out the space and build some more stores. As a mental exercise sometimes, when I’m in a really hopeless looking over-large strip mall, I like to imagine what it would look like if piece by piece, little bits of the parking lot were gradually turned into neighborhood extensions. All in all, many big box stores aren’t even necessarily that awful in and of themselves. In reduced lots with things built around them, they could be shopping hubs for a much more connected population.

Smart Providence voters would support the parking tax on big boxes also as a means of leveling the playing field. Providence has a minimum business tax, which means that you’re paying a fairly high premium just to start out, whether or not you’re successful. Lowering or eliminating this kind of tax, going to some kind of percentage tax, and having a surcharge on parking space could change that scenario. What a big box is doing is essentially wielding a huge weapon of amazing, awe-inspiring car access, but without having to pay for any of what makes that possible (environmental damage, loss of walkability, increased sewage runoff, increased sewer infrastructure, hundreds of thousands of dollars per intersection of signals, wider roads, etc., etc.). Small businesses are essentially paying those costs–the costs of taking away their own customers.

A per spot tax on all parking lots could be set up to have a deduction of sorts for the first X number of parking spots. I don’t really think this is necessary, because the net reality of a parking tax would be to return more property taxes to small businesses and residents than those small businesses or residents pay out, but we also have to be aware that many people don’t like to dive into complicated multivariable math, and if doing this makes it simpler for people to count the pluses and minuses in their life, then fine.

I wrote a lot about the concept of value-per-acre at EcoRI News some time ago. It’s an idea put forward by Joe Minicozzi, and I think people interested in building an equitable growth model that’s good for the environment would do well to familiarize themselves with his work. This also helps to explain this tax model more.

Residential parking

A concern is parking in shopping areas. How would a parking tax affect residential areas? I think the tax models above would have very diminished value in most residential parts of Providence, because in those areas the value of parking may be minimal compared to the effort of passing a law. However, there are parking policies we could institute that would help residential areas. Those I’ve loosely based off of parking guru Donald Shoup of UCLA.

A big tool would be giving renters a cash-out option on parking. As a beginning to this, renters who have a garage as part of their lease should be able to opt out of the cost of the garage if they don’t want to use it, because garage parking affects housing affordability. A rent of $1,000 for an apartment that includes one garage spot can be broken down into $600 for the room, and $400 for the garage. A lot of residents will be happy to pay for the garage if they use it, but forcing landlords to treat these as separate things will open up parts of the downtown to people with less money who don’t drive. The landlords would be free to open unused spots on the open market, which would also help get rid of surface lots, by competing with lot owners. There would be no tax on this residential parking, because forcing it to be treated as a separate commodity would have a downward effect on demand.

Many parts of Providence have driveways, a legacy of on-street parking bans of days of yore. It would be a real gain to get rid of some of those driveways, or at least people to put raised beds above them. Other driveways could be converted into “granny cottages” to add housing. But the reality is that driveways are just not worth anywhere near as much as garage spots, nor are they the severe blight on the city of surface lots. This might make a cash-out hard to calculate. Instead, why not nix the existing on-street parking permits entirely (Do I hear a huzzah?) and trade them for an equal permit cost on driveways. Parking on the street would be free in most residential areas. Think of this as a mini-credit towards green space. Homes that decided to park on the street would and use their driveway for raised beds, or that pulled up the paving on their driveway, or built a building extension into the driveway, would not pay the tax (although the building extension would be weighed into property taxes). Getting people to park on the street in residential areas would not only help green space, but would also slow down speeding. I know that getting rid of some of the driveways in Mt. Hope would make crossing my street much more pleasant.

For streets that got protected bike lanes (mostly arterials), the parking tax would be nixed, and no driveway tax would be issued either. The logic is that in some areas we may have to remove parking lanes to create safe biking, and if you’re not getting a parking spot out front of your house, why should you pay?

Donald Shoup talks about “right pricing” (click for video) parking, which is really just an issue in places where parking is in high demand (the idea is the lowest price that still keeps a couple spots free). Most residential areas are not going to run low on parking no matter what the price, but some that are near shopping districts would benefit from parking meters to impose a price on visitors and ensure that residents have a place to park. To make things simple, residents would pay meters, but the meter money would be taken off their property taxes. This also solves a big problem with the parking permits we have now–they’re by ward. What happens if you want to visit someone? You can’t park away from your house without worrying that you’ll get a ticket. This way when I visit you I pay, and when you visit me, you pay, but we both get 100% of the money off the taxes we were going to pay the city for our house. And. . . and. . . we’ll be able to find a spot.

A land tax

A land tax is not a parking tax, but it’s worth talking about, since my proposal for a parking tax is sort of a modified land tax. A land tax says that you should pay not just for the building you build on top of a piece of land, but also for its location and the type of zoning it has. So, for instance, a vacant lot is a particularly galling case of an owner flaunting the lack of a land tax in Providence, because since we only tax property value, it’s assumed that the prominent downtown location of a lot is worthless when it’s anything but.

The concept of a land tax gets slightly complicated though, and although I’m a believer in land taxes overall, I want to avoid some of those complications by going straight for a parking tax. For instance, what do we do about green space? If you own a house with a huge yard, should you be taxed extra just for the fact that your land is a half acre instead of a quarter acre or tenth of an acre? I think a lot of people might find this concept troubling, because even if it’s not our yard that we’re talking about, we just kind of like grass and trees, etc.

By the same token, what if we decide that downtown is worth a lot more in land taxes than some other place, but we find that some historic buildings don’t produce enough revenue to pay what they would pay as 20 story buildings in that location. Do we want to create a situation that might push them out, or encourage demolitions? A clever administration could draw exceptions and loopholes into a land tax to try to close the problems with this, but I just prefer going around it entirely and focusing on what we want to get rid of most: surface lots.

One concept that works really well from a land tax that we should use is modifying our tax structure based on location. I think a really good rule of thumb should be that a parking tax should be highest in places within 1/4 mile of frequent transit, a bit less 1/2 mile from frequent transit, and nonexistent where transit is nonexistent. Providence City Council could also choose to tax parking lots that are a adjacent to the front of a building differently than it taxed parking in the back of a building, since the latter has less of an effect on neighborhood walkability.

In the next piece I’m going to consider how suburban and rural areas of Rhode Island could best respond to Providence imposing a parking tax if they’re interested in saving their residents money. Stay tuned!