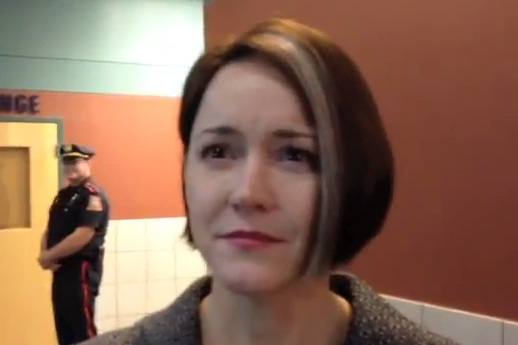

Tess Brown-Lavoie was found guilty of disorderly conduct for blocking the highway during the #blacklivesmatter protests on November 25 and sentenced to six months probation, 100 hours of community service and a $500 fine by Judge Christine Jabour.

Tess Brown-Lavoie was found guilty of disorderly conduct for blocking the highway during the #blacklivesmatter protests on November 25 and sentenced to six months probation, 100 hours of community service and a $500 fine by Judge Christine Jabour.

Defense attorney Shannah Kurland announced her intention to appeal the verdict to Superior Court.

The trial lasted about four hours, with the state calling only three witnesses. The key witness was Rhode Island state police officer Franklin Navarro, a ten year veteran who before joining the force was a practicing attorney. Navarro testified that he did not see Brown-Lavoie on the night the highway was blocked until she was already under arrest and placed in the back of a police transport van with the four other individuals. Navarro was able to identify Brown-Lavoie in the videos provided by WPRI-12 and WLVI-6, shot the night of the protest.

Defense attorney Kurland questioned the relevance of Navarro’s testimony. The officer, claimed Kurland, was not testifying exclusively to events he personally witnessed the night of the protest, but also on what he could see in the video that was shot by others while his attention was drawn elsewhere. Judge Jabour initially supported Kurland’s arguments, but then reversed herself as she allowed the prosecutors, assistant attorney general Stephen Regine and attorney Eric Batista, to slowly move through the 20 minutes of video asking Trooper Navarro to narrate what he was seeing, sometimes frame-by-frame.

Navarro scrutinized the video, pointing out figures in the crowd he claimed to be Brown-Lavoie based on her long hair, hoodie, jeans and “teal blue” shirt. The identifications Trooper Navarro made were not apparent to me or to many in the courtroom. Attorney Kurland spent some time pointing out inconsistencies in Navarro’s account, but Judge Jabour ultimately found the trooper’s testimony compelling, and cited Navarro’s testimony in her judgement as the main reason for the guilty verdict.

Navarro’s account

Perhaps the most interesting part of Navarro’s testimony was his description of the events that transpired on the night of the protest. Navarro arrived at the state police barracks on Route 146 in Lincoln just before the call came in about a disturbance on Route 95 near the Washington St. bridge. Four troopers in four cars responded from the barracks, and hit heavy traffic, caused by the protesters blocking the highway, where 146 meets 95.

Perhaps the most interesting part of Navarro’s testimony was his description of the events that transpired on the night of the protest. Navarro arrived at the state police barracks on Route 146 in Lincoln just before the call came in about a disturbance on Route 95 near the Washington St. bridge. Four troopers in four cars responded from the barracks, and hit heavy traffic, caused by the protesters blocking the highway, where 146 meets 95.

Navarro testified that he used his lights and sirens to cleave a path through the cars until the road became hopelessly blocked and he was forced to leave his vehicle and walk the remaining 100 feet to the site of the disturbance. Upon arriving at the scene, Navarro noticed orange traffic cones blocking the travel lanes. Navarro met with his commanding officer and then attempted to persuade the protesters to leave the highway verbally. After a “few minutes” the police organized a line and successfully corralled the crowd off the travel lanes and onto the breakdown lane and the embankment.

It was while ordering the crowd up the embankment and over the fence back onto the service road that runs parallel to the highway and alongside the Providence Public Safety Complex that Navarro noted an altercation and noted that his fellow officers were in the process of arresting two black men. Navarro focused on his portion of the crowd, commanding the protesters up the embankment and back over the fence.

It was while ordering the crowd up the embankment and over the fence back onto the service road that runs parallel to the highway and alongside the Providence Public Safety Complex that Navarro noted an altercation and noted that his fellow officers were in the process of arresting two black men. Navarro focused on his portion of the crowd, commanding the protesters up the embankment and back over the fence.

After the crowd was cleared and the arrests made, Navarro was then ordered to escort the van back to the state police barracks in Lincoln. It was at this point that he first saw Lavoie-Brown, who was in the van with the others arrested by the state police that night. Navarro escorted Lavoie-Brown and Molly Kitiyakara into the state police barracks for photos and fingerprinting.

Constitutional challenge

Judge Jabour dealt with a constitutional challenge to the disorderly conduct statute under which Brown-Lavoie was charged. (A copy of the memorandum, filed for another defendant, can be viewed here.) Attorney Kurland maintained in the memorandum that the law as written is vague, in that it states that protests on the highway are illegal, unless part of a legal protest. This leads to ambiguity, as differentiating between legal and illegal protests is not part of the law as written. Jabour rejected this reasoning, saying that the law “was not vague and could not be more specific” in listing the kinds of behavior the law is meant to curtail.

Kurland’s second objection was based on “time, place and manner” restrictions. The #blacklivesmatter in Providence protests were scheduled to occur the day after the grand jury verdict in Ferguson that ultimately brought no charges against Darren Wilson, the officer who shot and killed Michael Brown. Applications to the Rhode Island State Traffic Commission must be turned in 7 days in advance of an event, making timely protests all but impossible, in contravention of first amendment case law. Further, there is no history of a permit to protest on a highway ever being granted in Rhode Island, and there is the question as to whether our constitutional rights should be turned over to an administrative body such as the State Traffic Commission.

Judge Jabour also rejected this reasoning, saying that “laws are presumed constitutional unless the defendant proves [otherwise] beyond a reasonable doubt,” which in Jabour’s opinion, Kurland had failed to do.

Effects on proposed legislation in the General Assembly

Pending appeal, Lavoie-Brown’s conviction seems to demonstrate that new laws making blocking the highway a felony or a misdemeanor separate from disorderly conduct are unnecessary. The state has successfully prosecuted two cases under existing laws, and the penalties, though not as onerous as those suggested by Senator Leo Raptakis, are within the range being discussed in Representative Dennis Canario’s bill. Passing new laws after defendants have been successfully prosecuted and sentenced to sufficient punishment under existing law would seem to most people to be a waste of time and effort.

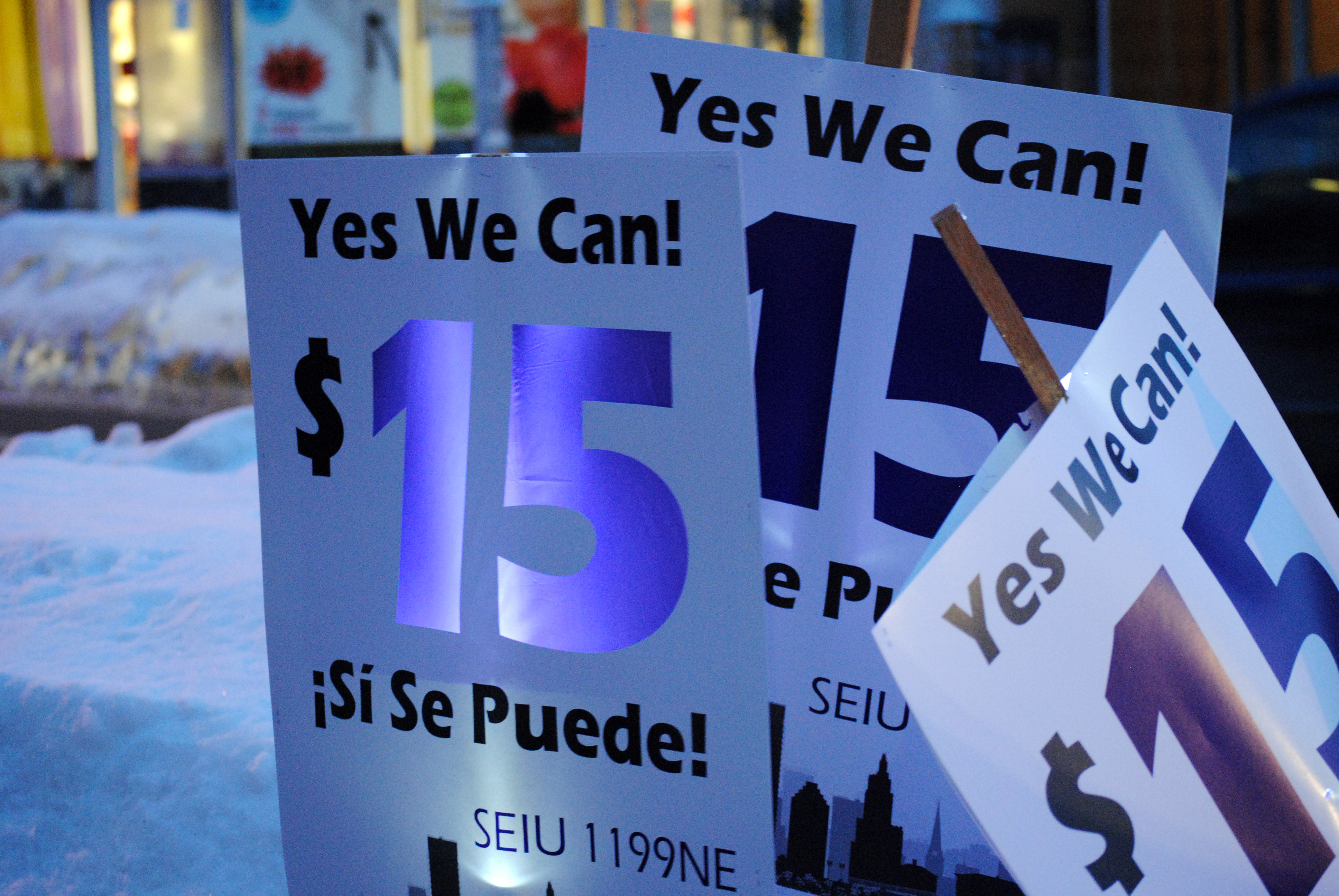

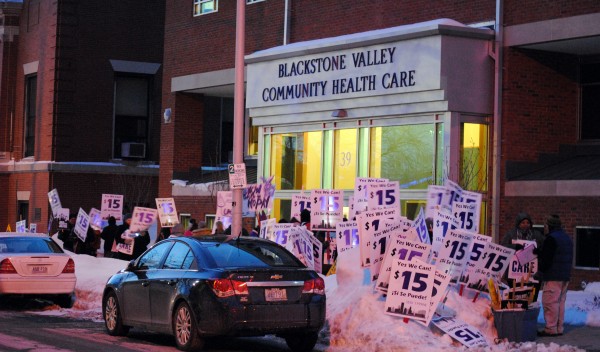

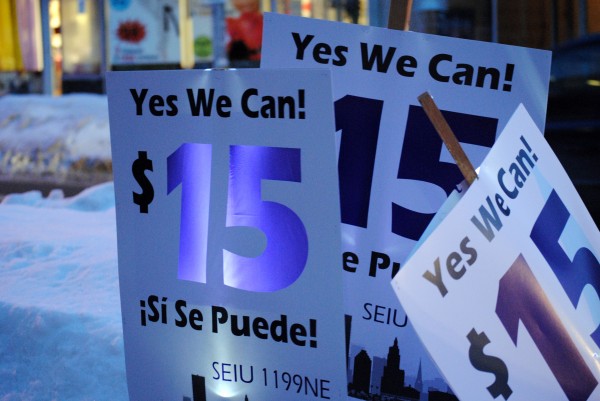

As the sun was setting and temperatures dropped, over seventy workers and supporters took to the sidewalks with illuminated “Yes We Can! $15” signs chanting in both English and Spanish outside

As the sun was setting and temperatures dropped, over seventy workers and supporters took to the sidewalks with illuminated “Yes We Can! $15” signs chanting in both English and Spanish outside  BVCHC has been expanding recently, capitalizing on the increase in business the health care provider has received under Obamacare. The number of patients served by the company has increased to over 15,000.

BVCHC has been expanding recently, capitalizing on the increase in business the health care provider has received under Obamacare. The number of patients served by the company has increased to over 15,000.