June in Rhode Island means two things: ripe strawberries and gubernatorial vetos.

June in Rhode Island means two things: ripe strawberries and gubernatorial vetos.

The silly way our legislature schedules things — with all important bills held until after the budget passes to ensure every legislator falls into line on that vote — means that hundreds of bills are passed in the last few days of the legislative session. This then means they all await the Governor’s signature after the session ends. And some of them get a veto instead.

My favorite veto so far this year was of a bill that would provide a tax break… at someone else’s expense. Sponsored by Representative John McCauley (D-Providence) in the House, and Senators Michael McCaffrey (D-Warwick) and Erin Lynch (D-Warwick) in the Senate, the bill would exempt from the property tax any new construction before it was issued a certificate of occupancy.

The collapse of the housing bubble has meant a real collapse in construction employment. Unemployment among construction workers is almost certainly much higher than the already way-too-high general rate lurking around 11%. It’s natural to think that the industry could use some help. But is it natural to demand that someone else provide it?

Essentially what this bill’s sponsors hoped would happen is to stimulate the construction industry by giving developers a break on property taxes collected by a city or town. One can applaud the motivation while still thinking that the concept is pretty weak.

First of all, it’s not at all clear that this would have a stimulative effect. How many developers are dissuaded from investing by the potential risk of having to pay taxes on property before it’s occupiable? Might not the lack of buyers be a bigger disincentive?

Second, how dare these legislators pile on to the cities and towns? This is a bill that would actually take tax revenue away from many municipalities. Do they not read the news? Are they not aware that we now have three cities in financial trouble, with more on the precipice? In what way exactly would this help those cities?

To be honest, this is hardly that unusual. After all, it’s almost traditional in the General Assembly to ignore or hide the cost of tax cuts. I can’t think of a single substantial tax cut over the past 20 years that passed the Assembly with offsetting cuts to services. In fact, the tradition is not only to avoid paying for tax cuts, but to vote to phase them in over several years so the real costs are hidden during the budget year they are debated. This was true of the 1997 income tax cut, the 1997 car-tax cut, the 2006 flat-tax cut, and the 2001 capital gains cut, which didn’t even take effect until five years after it passed.

So does this mean unemployed construction workers are out of luck? Probably it does, but not because there is nothing to be done. They are out of luck because the people who can do something choose not to. The General Assembly leadership feels that keeping state revenue down is more important than helping cities and towns. Three years ago municipal budgets across the state were vandalized when the state withheld part of that fiscal year’s state aid payment. Then they did it again the next year, and the next. Between fiscal year 2008 and 2010, the state withheld what amounted to about 10% of Providence’s non-school budget, and millions more for each other municipality.

Admittedly, the state saw its own revenues plunge in 2008, as the income and sales taxes both skidded down in the recession, accelerated by big tax cuts for rich people during each of the years 2007-2011. But the recession and the cuts are over, and revenue in the current fiscal year looks like it will end well ahead of last year’s projections. You might think that would allow us to restore the tax cuts and thereby restore the municipal aid cuts of the previous years, but apparently not. Or you might think we could engage in some small local stimulus, perhaps by accelerating the scheduled repairs of our bridges, maintenance of state buildings, or maybe even re-hiring a few hundred teachers. Nope. Tax cuts are still the only thing on the menu at the state house.

So bravo for Governor Chafee. Bills like this deserve a veto and the legislators behind them deserve to be shamed.

]]>

In the waning days of the legislative session, can one be forgiven for suspecting that Assembly members don’t give a, well how about a quart of sewage solids about the municipal governments they represent? Sewage stories from Woonsocket and Warwick lead one to suspect otherwise.

Woonsocket first. Woonsocket is currently under a DEM order to drive nutrient pollution down beginning in 2013. Nutrient pollution, in the form of nitrates and ammonia, acts as fertilizer for algae blooms that use up oxygen in the water, killing the fish that aren’t driven away. The estimated cost of these improvements is around $35 million. The system serves Woonsocket, but also some customers in neighboring towns, on either side of the border with Massachusetts. The estimate is that this will add a couple of hundred dollars to annual sewer bills.

Woonsocket’s now-infamous House delegation, Jon Brien, Robert Phillips, and Lisa Baldelli-Hunt, tried to get the DEM requirement killed during the last legislative session. Unfortunately, DEM is only enforcing a federal EPA requirement, so it’s more complicated than just yelling, “stop.”

Complicating the issue, upstream from Woonsocket, the sewage authority over the line in Massachusetts is suing the EPA over the same rules. The dodge currently preferred by the city of Woonsocket and their House delegation is that Rhode Island wait for the outcome of that suit. Though it might seem to make sense to wait for the suit to settle, similar suits around the country have failed. Besides, clean water is — to most people — a good thing. Might the delegation have proposed helping Woonsocket pay for the sewage treatment upgrades?

Move now to Warwick. The Assembly repealed a law to mandate that homeowners along the new sewer routes hook their houses up to those sewers. A typical hookup costs $1500-2000, and annual sewer bills are around $450. The mandate is/was part of the Greenwich Bay Special Area Management Plan, a plan to clean Greenwich Bay, once home to a thriving shellfish fishery, and now mostly closed to digging clams.

Governor Chafee vetoed the bill and the Assembly overrode his veto. Another victory for low sewer bills. Except that the finances of the Warwick Sewer Authority have budgeted in a certain number of hookups per year. This is part of how they borrowed the money to fund the expansion in the first place, and how they make their budget each year. Without those new hookups, the people already connected to the sewer will see their rates rise, both according to the financial statements, and to Janine Burke, the Warwick Sewer Authority director, who I spoke to about it.

Alternatively, the Authority has the legal authorization to charge a fee — a “connect-capable” fee of around $200 per year — to the houses along its route that aren’t hooked up. To date it has chosen not to do so (which puts it out of compliance with the Greenwich Bay plan), but it can revisit the issue. At any rate, overriding that veto in order to keep sewer costs down seems like it may be a losing strategy.

What both of these stories say is that the state is interested in seeing cleaner water. The Assembly gave no orders that DEM repudiate the EPA requirements. No one will go on record wanting dirty water and dead fish. They just don’t want to pay for the cleanup.

To a small extent, you have to give the Woonsocket gang of three a little credit for consistency. They don’t think cleaner water is worth spending any money on, and so reject both the money and the requirements, even if they offer lip service to clean water. Lisa Baldelli-Hunt told the Woonsocket Patch:

“I understand it’s important to decrease the pollutants in the water and I also understand that eventually, this must happen. But we can’t possibly move forward with this project at this time and consider ourselves fiscally responsible leaders.”

So their position is clean water, later. The rest of the Assembly seems ok with the idea of clean water now, so long as someone else pays for it. Neither perspective seems worth endorsing to me.

What about the perspective that clean water now is a good thing worth paying for? It’s a good thing for Woonsocket, but it’s also a good thing for everyone downstream, which means Lincoln, Cumberland, Pawtucket, Central Falls, Providence, and everyone on Narragansett Bay. Untreated sewage currently flows into the water from the Warwick shore, but East Greenwich benefits from a cleaner Greenwich Bay, too. Given all that, why should the state insist that all sewage problems be solved locally? Yes, Woonsocket residents pay higher property taxes proportional to their ability than nearly any other city or town in the state. Sewer customers in Providence and Pawtucket have seen their rates climb dramatically in recent years for the same reasons. Does the state have nothing to offer besides words? How about money?

Let’s end with a riddle. In 2010, our state’s economy, measured by the gross state product, was about $49.2 billion dollars. Corrected for inflation, this is larger than it has ever been in our little state’s history, despite our monumental unemployment rate. There are those who say that our economic growth is because of the dramatic drop in tax revenue over the past decades. That’s silly because growth has slowed or stalled as taxes have been cut. But slow growth or fast, the economy now is bigger than ever.

So remember, when you hear about how we can no longer afford clean water or good education or comfortable retirements — let alone find enough jobs for everyone — that our state is collectively richer now than it has ever been before. Ever. Feel better now?

]]> Who cares about buses? Apparently no one on Smith Hill.

Who cares about buses? Apparently no one on Smith Hill.

The House Budget, to be voted on Thursday, contains not a penny in new revenue for RIPTA. It also contains no ideas, proposals, or signs that anyone in the House Fiscal staff spent more than a dozen minutes thinking about the agency. This is hardly surprising, since the Governor’s budget didn’t have anything to say about it, either. Despite several years of a funding crisis, RIPTA still struggles to get anyone’s attention.

This, of course, is also hardly surprising. No one in a position of authority actually rides the bus. The Governor doesn’t, the Speaker doesn’t, the Senate President doesn’t, even though the service from Newport to Providence is excellent, with over 60 buses traveling back and forth every day. There aren’t even any members of the RIPTA board who are regular bus riders, besides Anna Liebenow, who has MS and uses a wheelchair. Two current board members have told me they made a point to get on the bus once or twice after their appointment, but that’s not quite the same thing, is it?

This isn’t to say that no one rides the bus. RIPTA provided 26 million rides last year, which works out to serving between twenty and fifty thousand people every day. Over half of them are riding to and from work (like me). Lots of them own cars, which they leave at home to leave more room on the highway and more parking spaces for you.

And, of course, lots of them don’t own cars, or can’t drive, and the bus is their lifeline, the way they get around this state. But who cares about them? In the halls of the state house, RIPTA is widely viewed as a program for poor people. Consequently it is a poor system, and it’s therefore socially acceptable in that world to ignore it. There are a couple of seats on its board designated for people who represent either poor people or disabled ones, and that’s pretty much that.

The House budget does provide for some capital investment to buy new buses, but that’s not RIPTA’s problem. Their problem is that a big part of their budget comes from the gas tax, and when gas prices rise, more people ride the bus and less gas is sold. Since the gas tax is a set number of pennies per gallon of gas (9.25 cents out of the 32 cent per gallon gas tax), when gas prices rise they get more riders at the same time they get less money. It’s a crazy way to fund the system, but that’s nothing new. Now, despite several years of three-dollar gas and full buses — standing room is not unusual on the lines I ride — there has been zero constructive action to fix the problem.

You should understand a couple more things about RIPTA. One is that compared to other similar sized systems, we get very good return for our dollar from the agency. Comparing rides provided per year to expenses, RIPTA comes out very well in head-to-head matchups with its peers around the country. The other is that to my knowledge, except for a one or maybe two subway lines in Japan, there aren’t any public transit systems anywhere in the world that don’t have a subsidy of some kind. Just as there aren’t any road systems who don’t require a subsidy. Public transit is a matter of public infrastructure and should be supported as such. We’re not talking about a mint. RIPTA’s deficit is estimated at about $9 million at this point, a little more than one thousandth of the overall budget.

At the current deficit, and with no change at all, RIPTA has approximately half a year left before they can’t make payroll. This won’t happen, of course. What will happen is service cuts that will be devastating for everyone who relies on the bus. Without buses there will be around 10,000 more cars on Rhode Island roads every day, along with many more people than that cut off from jobs they travel to, or just unable to get around because they can’t afford a car — or because they can’t drive.

So come on, tell your Representative or Senator that we need public transit. (And do it today!) We don’t need more buses without the money to run them. Call Helio Melo, the House Finance chair and tell him that just because he doesn’t ride the bus doesn’t mean that nobody does. Tell Gordon Fox that not everyone can afford a car. Tell Teresa Paiva-Weed that our state will be a cleaner, more pleasant place to live — and drive — with a healthy and well-funded bus system. We need more people on the bus, not fewer, and letting RIPTA choke on gas tax fumes is exactly the wrong direction for our state to be going.

]]>

I see from the Providence Journal that the new state-appointed budget commission has decided that the city council and Mayor Fontaine were exactly right to request permission from the state to impose a supplemental tax increase on their citizens.

Last week, after an impassioned speech by Rep. Lisa Baldelli-Hunt, the House rejected Woonsocket’s request. This week, the state-appointed budget commission asked that the request be reconsidered.

For some reason state legislators seem to get this idea in their heads that though they were elected on promises of fiscal responsibility, and intend to carry through on them, city council members and mayors get elected by promising to spend like drunken sailors.

This is not only bizarre, but entirely backwards.

By almost any measurement you care to make, it’s the state that has been the fiscal problem child over the past couple of decades, not the cities and towns. The difference is that the state has power over the cities and towns: they have more money, and stand uphill in a legal and constitutional sense, too. But the General Assembly continues to resist the appeals of the duly elected leaders of our cities and towns, feeling that they know better.

This year, Governor Chafee infuriated organized labor by offering several “tools” to municipal officials to help them control pension costs. I tend to agree with the labor folks here, that the state should stay out of these issues, and that passing state laws to trump local bargaining agreements is only a good idea in a very limited short-term sense. But the Assembly has shown no interest in believing Mayors when they complain about financial stress, so if you don’t want more bankrupt cities, what should you do? It seems to me that Chafee wasn’t so much sticking his thumb in Labor’s eye as making a realistic assessment of the Assembly and acting accordingly.

Or maybe not. It appears that the Assembly leadership isn’t interested in Chafee’s suggestions, and pretty much none of them were put into the House budget. This reminds me of the time in 2005 when the Carcieri administration came up with some personnel reforms that might have saved around $32 million. They were the usual sort of benefit cuts, limits on vacation time and sick time and an end to “statutory status” which is a kind of state employee tenure.

Whatever you think about the wisdom of those reforms, it’s hard to praise the Assembly for what happened next. The legislature rejected the reforms — but left the $32 million in savings in the budget. So the administration was faced with finding $32 million in savings, but without the law changes to do it. How, exactly was that responsible?

So now the Assembly is poised to do the exact same thing, and act to increase the pressure on cities and towns — not enough money to support their commitments, but no relief from those commitments, either. The only difference this year from previous years is that now we have some Assembly appointees joining the Mayors in the hot seat, begging that they not be put in the same position as the Mayor and City Council of Woonsocket. Mayor Leo Fontaine and the Council have failed to keep Woonsocket solvent, but a new budget commission won’t do any better unless the conditions change. Right now, the only way the conditions will change is through the bankruptcy court, so mark your calendars. I simply can’t agree with the people who imagine that dragging each of our cities into bankruptcy is a sensible strategy — in either the long or short term — for our state.

The Assembly can act here. Sensible options are available, that take into account the actual realities facing our cities. But will it? So far, it does not appear likely.

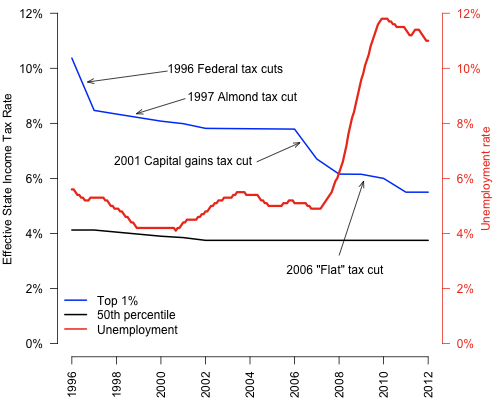

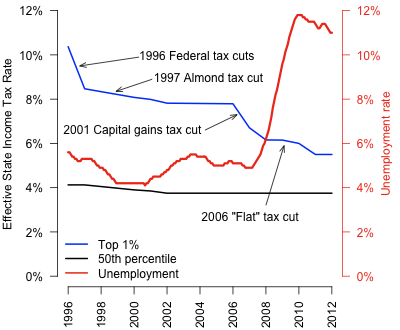

]]>This graph is still the policy of the state:

That lower line is the effective tax rate on the median taxpayer. The blue line is the rate on the top 1%, and the red line is just thrown in there to show there is no relationship between taxes and unemployment.

The message overall from the legislature is that the cities and towns be damned. There seems no willingness to acknowledge that the fiscal crisis in the cities is largely the result of state policies. Tremendous cuts in state aid in 2008-2010 to both the municipal and education sides of city and town budgets brought fiscal havoc everywhere, and last week we had the spectacle of Lisa Baldelli-Hunt, a representative from Woonsocket, begging her colleagues in the legislature not to allow Woonsocket to fix the problems caused by her colleagues. Oddly enough, they complied, and now we have two more cities half a step from joining Central Falls in bankruptcy.

The sad fact is that by and large the people in charge of our cities and towns have actually been more fiscally responsible than legislators in the General Assembly, but they have less power, and so the Assembly leadership can pretend otherwise.

That’s quite a claim, isn’t it? How to back it up? How about this: as of 1990, Rhode Island cities and towns collected about $1.3 billion, between state aid, property taxes and various municipal fees. In 2008 — before the worst of the state aid cuts — they took in a bit less than $3 billion. This does not count the car tax payments from the state, which only offset taxes that towns would have collected from their residents. If you’re keeping score, that’s growth of about 1.9% per year — after correcting for inflation. This is troubling, but it’s not necessarily evidence of mismanagement. Inflation measures the price of goods and a few services, while towns spend their money on services and a few goods.

So how best to measure this if not against the inflation rate? If you want a yardstick with which to measure a service-oriented enterprise like a town, how about a private-sector service like Federal Express? Fedex is fiercely competitive, I hear, and non-union, to boot. How did they do? In 1990, it cost $11 to send an overnight letter across the country, and today it’s about $25.50 for the same service. After correcting for inflation, that’s up about 2% a year.

What about the state? After accounting for inflation in the same way, the state’s general revenue has gone up 2.4% per year since 1990, and overall expenses are up even more. (That’s the structural deficit and the rise in state debt you’re smelling.)

So who is being more responsible with tax dollars? The General Assembly, with members like Baldelli-Hunt who give lectures to municipalities, or the towns, who have controlled costs not only better than the state, but better than Fedex. But it’s the towns who get cut while the state basks in the adulation of business leaders who praise legislators for their tax cuts.

The main message of this budget bill is continuity. This is a budget motivated by policy choices virtually identical to the ones of the previous year, the year before that, the year before that, and so on. The idea is to squeak through another year with minimal pain to everyone, especially the wealthy. But it was to a large extent that very set of policies that brought us to the status quo: high unemployment, bankrupt cities, ever-rising tuitions at the state colleges, and lower taxes on rich people.

Do you like the way things are going around here? Hope you do, because the legislature is voting this week to give you more of the same.

]]> A correspondent tells me that last week there was a meeting over at University Heights where some residents got bad news about their rent. University Heights was built in the 1960s as a mixed development, split about half and half between market rate apartments and subsidized apartments, available to poor people and families. It’s had quite a history since then, including a period in the early 1990s when it was owned by the tenants’ association.

A correspondent tells me that last week there was a meeting over at University Heights where some residents got bad news about their rent. University Heights was built in the 1960s as a mixed development, split about half and half between market rate apartments and subsidized apartments, available to poor people and families. It’s had quite a history since then, including a period in the early 1990s when it was owned by the tenants’ association.

The recession of the early 1990s brought that dream to an end, and Rhode Island Housing became the owner. In 2006, they sold the project to Fairfield Residential, securing a promise that the affordable units (175 of them) would remain below market rent for forty years.

Now there are a couple of things you have to understand about the practice of affordable housing. One is that almost all the housing out there built under the title “affordable” has a term, at the expiration of which it converts to “market rate” housing. The term might be for 20 years, 40 years, or whatever, but after that, the landlord can rent it for whatever they can get. Sometimes the affordability is extracted from the landlord with a promise of rent subsidies. Other times it’s made in exchange for lower acquisition cost, low-rate financing, or some other way to save money on the project. For an older project like University Heights, most of these ways are not possible, since the project was built long ago. This leaves rent subsidies as the only practical option.

Last week, though, RI Housing announced to some distressed tenants that the apartments they live in have to be transferred to another, less generous subsidy program. Essentially the agency cannot afford to keep the subsidies at the level they had been, so in 2014, the rents for 48 of the apartments will rise substantially.

Why can’t RI Housing afford to keep the more generous subsidy? Well, in the winter of 2008, as Governor Carcieri looked to the end of the year, there was a looming shortfall. Not only was it the second year of the “flat” tax cutting into revenues, but the coming recession’s bite was already being felt in sales tax collections, too. Rather than admit that the state couldn’t afford the tax cuts under the current conditions, the Governor looked around and noticed $26 million on the balance sheet of RI Housing. So he scooped it out of the housing agency and into the general fund, in order to balance the state’s budget that year.

Why was there a deficit in the winter of 2008? Partly because of the recession, but also because some of the tax cuts for rich people turned out to be too big. The historic tax credit was too popular, and the renovation of the Masonic Temple hotel used them heavily. The tax credit program was ended that year, because so many credits were outstanding. The data can’t tell us exactly how much these cuts cost, but the income tax receipts that year came in $23 million less than predicted. Personal income in the state didn’t begin to fall until months later, so it’s hard to attribute the loss of income tax collections to the faltering economy.

The $26 million lifted from RI Housing was to fill a small part of a budget hole due in no small part to income tax cuts for rich people. But it wasn’t lying in RI Housing’s accounts unused. It was money intended for the purchase of housing, for subsidizing rents, and for the construction of new units. In other words, it was intended for the benefit of poor people, but Governor Carcieri — and the willing General Assembly leadership — redirected it for the benefit of rich ones. Can there be a clearer example of our state’s priorities over the past decades?

]]>In the discussions of taxes at the State House, one line you hear a lot this year is that our state’s new income tax code is new and we should give it time to see how it works out. That’s what House Speaker Gordon Fox has said, and I’m hearing that it’s the line of the day on Smith Hill, available from any of the House or Senate leadership.

This is, of course, a silly point to make. The tax changes made last year basically just baked in the low taxes on rich people offered by the “flat tax” alternative. It used to be that a rich person could choose whether to pay tax under the tax code everyone else uses or using the flat tax limit, and now the flat tax limit is part of the code everyone else uses. This part may be new, but the overall “strategy” at issue — lower taxes on rich people, expect economy to get better — has been the order of the day in Rhode Island for a long time. To illustrate what’s really been going on in Rhode Island tax policy, I put together the following graph.

The blue line is the effective RI income tax rate on a fairly typical taxpayer in the top 1% over the last 16 years, with the various cuts that taxpayer has received indicated. These cuts don’t count tax credits like the film production or historic structures credits, which are typically only available to high-income individuals and which make the effective rate even lower. The black line indicates the effective tax rate on the median taxpayer (the 50th percentile). You can see a slight decline in the 1997-2002 period, but the other changes didn’t do much of anything for them.

The unemployment rate, of course, has nothing to do with the tax rate, except as a rhetorical club used to beat people about the head and neck. There is no evidence that it has any causal relationship with the state tax rate (in either direction), but the relationship between taxes and “job creators” is commonly invoked to persuade lawmakers to support lower taxes. I’ve included the unemployment rate on the graph as a service, so you can see how little is has to do with the movement of taxes.

One more thing you should know about this graph. There is some evidence available that the 2012 tax changes raised taxes substantially on the middle percentiles of taxpayers. Unfortunately, it’s premature to say more than that, since the data won’t be available until later this year, at the earliest.

The House Finance Committee is holding a hearing on several bills designed to raise taxes on the top 1% Tuesday afternoon at 4:30pm in State House room 35. Rep. Maria Cimini (D-Providence) is the prime sponsor (with 36 co-sponsors) of a bill to raise the taxes on people earning more than $250,000 per year by four percentage points, with that top rate coming down as the unemployment rate also goes down. Think of it as a “pay for performance” clause for rich people. There are also bills by Rep. Larry Valencia (D-Charlestown, Exeter, Richmond) and Scott Guthrie (D-Coventry) that will have more or less the same effect, though the income limits and tax changes are slightly different (neither of those bills have the unemployment clause).

]]> Should URI Faculty get a 3 percent raise? Let me tell you a story and you decide.

Should URI Faculty get a 3 percent raise? Let me tell you a story and you decide.

URI is the big kahuna among the three institutions run by the Board of Governors. It educates about 16,000 students, around 10,000 of whom are from Rhode Island. Researchers there pull in about $80 million each year in research funding, largely from federal sources, like the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health, but also from corporate sources.

There are some important financial issues going on at URI, and none of them are about raises for faculty. One is that state dollars continue to decline in importance to URI’s budget. Twenty years ago, state general revenue funding of $57 million provided about a quarter of the overall budget of $214 million. Today, we provide $75 million for a budget of $705 million, or just a tiny bit more than 10% [B3-46], making URI essentially a private university with a small public subsidy. State contributions over that time grew at an average rate of 1.3 percent per year while the overall budget grew more than four times as fast.

The Governor is proposing to raise the state’s contribution by a little more than $3 million, which is $2 million more than level funding, so that will hike the percentage of the budget contributed by the state a smidge.

But wait, shouldn’t we be concerned about growth of more than 6 percent a year? Why yes, we should. This is a national problem; universities across the country are seeing this kind of cost inflation. Tuitions are pretty much the only thing around that rivals health care costs in the inflation department.

So what is URI spending its money on? Answer: Not professors. To teach more or less the same number of students, URI has almost a hundred fewer professors than it did in 1994. (I’ve used the 1994 personnel budget in this, because they changed the presentation that year and it matches the 2013 presentation better.) In 1994, the “Education and General” part of the budget had 623 professors of the three ranks (full, assistant, and associate), and in 2013, we expect to have 540. The collection of all full professors have seen their pay climb about 2.8% per year over that time.

Looking at the administration shows a different picture. The top couple dozen administrators—the deans, provosts, and vice presidents—have seen their pay go up an average of 4.5 percent per year. There aren’t more people at the top level of administration, but in 1994, there were 65 people with the title of “Director” of something (or assistant director), and in 2013, there are 89. Individually, their salaries didn’t grow quite as fast as all the deans’ and vice-presidents, but because there are so many more of them, they also saw approximately a 4.5 percent average growth rate.

That kind of growth is high, but doesn’t make it to 6%. How about capital projects? In 1994, URI spent $6.4 million on construction and debt service. This year we’re looking at $68 million, and next year it will come down to $59 million. This is a growth rate of 13 percent a year! If you walk around one of the URI campuses, you’ll see lots of new buildings. But few of them are very crowded.

The other huge growth is in the account that provides student aid to cover rising tuition costs. Tuition this year is expected to go up 9.5% as it has for a number of years in the past. Consequently, the aid bill also rises very fast.

So that’s the story: declining aid from the state, declining numbers of professors, increases in administrator pay and numbers, construction of fancy new buildings, and huge increases in tuition. The construction part makes it seem like investment, but all together, does that really sound like an investment in education to you?

There’s another dimension here. By 1995, URI had already lost a tremendous proportion of its state aid budget. In 1989, state dollars covered 58 percent of the budget, but by 1994 it was down to a quarter. This was a crisis. The University (under its new President Robert Carothers) responded by doing a revenue analysis of all the departments, to see which ones made money, and they abandoned most of the programs that didn’t. They stopped admitting students in 47 degree-granting programs, including 16 in science and engineering. From a financial perspective, this seemed to make sense, though it was virtually unprecedented in American university administration.

From an academic perspective, the benefit was hardly as clear. Consider philosophy. URI still teaches some introductory level philosophy courses, so they still need some faculty. So if you love philosophy enough to pursue a doctorate in it, what URI has to offer you is a career of teaching classes to students who don’t really care about it. This immediately makes URI a second choice for anyone in that field. Maybe you don’t care about philosophy, but there were 46 other programs that got the same treatment. Is that the best way to get good faculty? How about not giving them money?

Now I learn from a 2010 “Research and Economic Development” presentation to the URI Strategic Budget and Planning Council that over the ten years from 1996 to 2006, URI saw its research funding grow by 29 percent. Over that same time, UNH saw its research funding up by 271 percent, UVM’s went up 162 percent, and UConn saw its funding rise 136 percent. (All larger than the national average of 117 percent.) This was immediately following that downsizing. Do you think maybe this could have been related to a shrunken faculty? Downsized programs?

The presentation was clearly meant to show how worried the University should be about this poor showing. After all, after educating students, research is most of the point of an institution like URI. Research brings in grant funding, research builds prestige, and research is where the real economic benefit of universities comes from.

But not to worry. The folks who put together this presentation had a plan, which was, I gather, put into action. Their plan: Create a new Vice President.

]]> Our budget tour continues with a visit to the Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities and Hospitals. The acronym is BHDDH and I’m told by insiders it’s pronounced “buddha.”

Our budget tour continues with a visit to the Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities and Hospitals. The acronym is BHDDH and I’m told by insiders it’s pronounced “buddha.”

BHDDH is spending more time than usual in the news. This is largely because last year they cut $26 million from the budget that would have gone to private providers of care for disabled adults. You can see the cut on page 153 of Volume II of the budget (or page 17 of this excerpt), second line, where $206 million in 2011 went down to $180 million in 2012.

This is a cut about three times as big as Governor Chafee proposed. But if you remember, the General Assembly rejected Chafee’s sales tax changes, so they had to cut much deeper than he’d suggested.

Some background: Rhode Island provides services to these people in two ways. About 220 get services through Rhode Island Community Living and Supports (RICLAS), a state program, and a bit more than 3,000 others get services through private agencies who bill the state for their service. These agencies are almost wholly dependent on those bills.

BHDDH recently commissioned a big study of the matter and determined that the state actually doesn’t pay very much for this service. Over the last few years, the population under care grew slower than any northeast state besides Massachusetts, and we reduced the per capita expense from $76,803 in 2009 to $63,013 in 2011. This is despite being one of only nine states (out of 44 where data was available) without a waiting list for services. In other words, we appear to be getting pretty good service for our money.

There is another side, though. We get this great value by paying people very little. The going rate for direct support staff at the private facilities appears to be between $9 and $11 per hour, even for the unionized folks. Remember, these are the people who are bathing, feeding, teaching, and otherwise caring for highly disabled individuals. By contrast, direct care staff at RICLAS are paid about twice as much. (Representative Scott Slater has sponsored a bill in to set a minimum wage for direct support staff at these residences.)

Conversely—and somewhat unfortunately—some of the executives at the private organizations are paid far more than their counterparts in the state. David Jordan, the CEO of Seven Hills, who runs homes in Massachusetts, too, was paid $533,214 in 2009. ($265k in salary and the rest in pension contributions.) This year he has responded to the budget cuts by cutting support staff pay by 5% and ending most of their benefits. Executive pay was cut 3%, according to UNAP, the union representing workers there.

So what happens when the administration makes a plan to cut costs and the Assembly says that’s great, but please cut three times as much? Answer: some pretty dumb things.

For example, the state will only pay a fee for service provided, as opposed to a per-person “capitation” rate. This sounds fair, but if an employee shows up an hour late to work, the agency gets docked not only that employee’s pay, but also the overhead costs allocated to that hour of pay. It’s not as if the agency wasn’t responsible for that care, or the heat and electricity didn’t have to be paid for that hour.

The state also changed the way they assess the level of disability for each resident. This affects the amount the state pays for their care. We had been using a four-step measure, but it was changed to a seven-step “Supports Intensity Scale” (SIS). The SIS is probably a better measure, but the four-step scale doesn’t exactly translate over to the seven-step one and the staff to do re-assessments simply doesn’t exist. Result: BHDDH simply decided which levels of the old scale corresponded to which levels of the new scale, and voila, they had to pay less to support the residents.

Actually, what BHDDH says is this:

If SIS has not been performed and client is receiving services then, the resource allocation is based on previously approved level of service cross walked to the new levels effective 7/1/11.

So what do we learn from this? That there isn’t much deference to department plans in the Assembly, for better and worse. If you’re a department director with a plan to cut costs, you should probably only present a fraction of those costs, or risk having your department turned upside down by a demand to cut much more. The promise of cuts is like blood in the water; the sharks don’t care where they bite, and presto you have people mobilizing marches against you. Under these conditions, which director is going to volunteer cuts again?

And we also learn about the downside of privatization. Through aggressive use of private group homes and community-based care, Rhode Island has kept costs low, much lower than most northeast states. But part of the reason we could do that is that the private operators of those homes didn’t have to pay their employees well (and could pay their executives too well). Though I’m sure it would help (at some of the agencies), slashing executive pay won’t make up for the cuts; there simply aren’t enough executives with egregious salaries to make up $26 million.

Overall, administrative costs at the private agencies (about 10%) seem comparable to the RICLAS costs, as far as one can tell from the personnel lists in the budget. More important, because these are private agencies, we have only limited control over them. As some will recall, that was part of the point of the whole privatization push. We were to give up control of services so the invisible hand of the private market could work its magic. Well it has, and here’s the result.

None of this is to say it isn’t possible to squeeze costs down over time, but how much less do we want care-givers to be paid? Though we would like to be able to slowly reduce administrative overhead, the sudden cuts of this past year will not have that effect. More likely they’ll bankrupt one or two of the providers, and that will be a lesson to…someone.

Full disclosure: I have recently done some software consulting work for West Bay Residential Services, one of the DD residential care providers, and may do so again someday.

Update: Clarified the makeup of David Jordan’s 2009 compensation.

]]> In volume II of the budget, you’ll find there the Executive Office of Health and Human Services (EOHHS), which contains the Departments of Children Youth and Families (DCYF), Health (DoH), Human Services (DHS), and Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities, and Hospitals (BHDDH).

In volume II of the budget, you’ll find there the Executive Office of Health and Human Services (EOHHS), which contains the Departments of Children Youth and Families (DCYF), Health (DoH), Human Services (DHS), and Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities, and Hospitals (BHDDH).

Collectively these departments spend over $3 billion, about 40% of the overall budget. In the Governor’s budget, only about 40% of that is actual tax dollars, and the rest is either federal money or restricted receipts, such as fees for service.

The big kahuna in the Human Services budget is, of course, Medicaid, so we may as well begin there. The expense for Medicaid has been moved from the DHS budget to the umbrella EOHHS. This, of course, means nothing to the budget’s bottom line, only that the accounting for that expense appears on page B2-118 for years before FY12 and before, and on B2-12 for FY13 and beyond.

So much for where to find it. How much is it? The Medicaid budget for next year is projected to be $1.66 billion, approximately the same as was originally budgeted for this year.

The same as this year? But what about the skyrocketing medical inflation? It’s there, but masked by offsetting cuts in service. The “Managed Care” portion of Medicaid that you see in the breakdown of the Medicaid costs is also known as RIte Care, and it has more than doubled in ten years, though it still amounts to only about a third of all the Medicaid. The annual cost increase for Managed Care has been about 7.5% each year. Eligibility rules tightened, but demand increased, so that includes a very minor decrease in enrollment over that time. What’s worse, federal reimbursement paid for 55 cents of every dollar in 2003, almost 64 cents in 2010 (part of the stimulus package) and only 51 cents in 2013.

In order to control these costs, the state has added or increased co-pays and restricted eligibility several times in recent years. Apart from that, there has been little more than some studies and planning from Lt. Governor Elizabeth Roberts in response to this ongoing disaster—remember, this affects everybody, not just the state budget—and this year is no different. The Governor’s 2013 budget will cut all dental care for adults to save $2.7 million. “Refinements to Medicaid managed care programs” will save another $2.5 million [ES-56]. Lots of these refinements involve cutting services, though some, like providing more care through “Patient-Centered Medical Homes” are potentially good ideas, depending on how they’re implemented.

One problem with the push for managed care is that in some cases it may well insert a new layer of bureaucracy where none is needed. A director of a residential care provider pointed out to me that his agency is already providing managed care for most of their residents. That is, with the advice of a consistent array of medical professionals, the agency selects care options for its residents. This is pretty much what the medical home concept suggests. If new requirements simply force them to add a layer of doctors to what they’re already doing, it won’t necessarily reduce any costs or improve any care. (It also calls into question the cost savings estimates for the managed care push.)

The other big component of cost saving in Medicaid is a proposal to save another $14 million by simply paying 4% less for the care.

Paying less? Who knew you could just solve the health care cost problem so easily. Why didn’t we think of this years ago? But yes, the Governor’s budget proposes paying 4.14% less for all Medicaid coverage that require a monthly per-person fee (“capitation”). This is mostly Neighborhood Health Plan, though United Health also has a share of that market. Neighborhood, though, has the misfortune of being in the business of serving the Medicaid population almost exclusively, so they will be much harder hit than the other two. Obviously any cost cutting reform has to start somewhere, but it’s hard to see how this will do the trick.

It’s worth an aside here to mention one of the factors in health care cost inflation that seems never to come up in serious discussions of the rising cost of health care. After all, what’s the fastest-growing component of a medical practice’s expenses? More likely than not, it’s health insurance for its employees. For all the fancy machinery of modern medicine, it’s still a labor-intensive business. A giant facility like Rhode Island Hospital puts more than half its budget towards salaries, and a small practice will see an even higher fraction, 70% or more.

A physician’s assistant earning $65,000 a year is probably receiving a health benefit worth around 20% of that if he or she has a family. What’s more, all those pharmaceutical firms, medical device manufacturers, and bandage makers also have to deal with rising health care costs. In other words, a significant part of what an increase in health care costs pays for is… an increase in health care costs.

This sounds like a dopey little irony, but engineers call this a feedback loop, and electronic systems with less feedback than this also spiral out of control. Obviously there are plenty of factors driving health care inflation—not least the vast number of people who see health care as a way to get rich—but at root, linking health care and employment creates an unstable system, prone to amplify increases. Could that not be worth some attention?

Next: Food inspection dereliction

Read more from this series