A few years ago, the Ocean State Policy Research Institute put out a very funny study that tried to use IRS migration data to demonstrate how high taxes were going to cost Rhode Island millions of lost dollars when people were driven from the state. The document had lots of footnotes, so it looked like a study, but the authors hadn’t noticed the IRS data they cited was about the movement of people, not money. That is, the OSPRI report only proved the authors hadn’t read the technical report on the IRS data before sending out the press releases.

OSPRI is gone now, joining the Education Partnership, ripolicyanalysis.org, the Citizens Foundation, and many more in that angry Valhalla of conservative Rhode Island think tanks. But don’t despair! The RI Center for Freedom, Prosperity, Motherhood and Apple Pie (CFPMAP) is here to fill this terrible void. As I’ve written, researchers at CFPMAP are behind the ongoing discussion, such as it is, of the sales tax decrease.

When you go read the supporting documentation behind the CFPMAP claims about the economic impacts of the sales tax decrease, you find they use an economic modeling tool they call RI-STAMP.

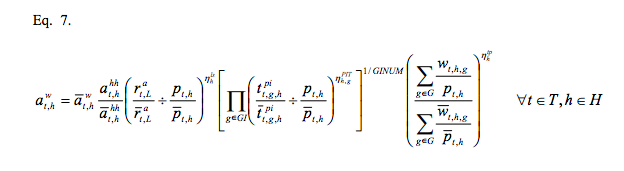

The RI-STAMP model is based on the STAMP model, developed by the Beacon Hill Institute at Suffolk University. Beacon Hill has done us all the service of publishing a lovely technical report on the model, filled with dense and intentionally impressive equations like the one here, which might distract the unwary from sentences like these:

“The savings rates for households at each income level were adjusted based on professional judgement [sic]…” [p.15]

“The trade data for the state are not particularly reliable; we have used our judgement [sic]…” [p.21]

“As with export demand we have used our judgement [sic], combined with BEA data, to arrive at sensible estimates [for import demand].” [p.21]

“Information on flows between the state and the rest of the world is difficult to piece together, and is an area where considerable professional judgment is required.” [p.11]

“We used professional judgment in determining the proper elasticities for each household group.”[p.16]

This last one was an estimate of how likely poor people are to avoid work if welfare payments increase. They described this professional judgment:

“The participation rate for low‐income households is assumed to be highly sensitive to the level of transfer payments, but relatively insensitive to changes in taxes or the [wa]ge rate. On the other hand, high‐income households are assumed to respond substantially to changes in the taxes and wage rates they face.”

In other words, a rise or fall in wages has a large impact on the behavior of high-income households, but a much lower impact on the behavior of low-income households. The latter are, however, assumed to be quite sensitive to the level of welfare payments. This is, shall we say, a debatable proposition, even in the economics literature. As are the other propositions on which they exercised their “judgment.”

There are also questionable assumptions about how federal dollars are spent in Rhode Island, whether all sellers of labor and capital can find buyers (unemployed much?), the extent to which businesses who have profit here also have owners here, and much more. One can go on at some length, but why bother? The model is, like most models (including the ones I use), a collection of predictions developed from the assumptions of the researchers who put it together. Dependence on assumptions is nothing extraordinary. It’s burying those assumptions under a collection of poorly-explained and almost parodic equations that is nothing more than intellectual bullying.

The performance of a model like this can be tuned on past events. We’ve had lots of tax cuts these guys could have practiced on. Did their model say tax collections went up despite the tax cuts of 1997-2002, 2001, 2005, or 2007-2011? If so, they don’t say. If the model can properly model those past realities, then you’ll potentially have something useful to predict future ones. Without that, all the fancy equations in the world can’t sell your results.

Hide the bias

The RI CFPMAP writers praise “dynamic” modeling of tax policy changes over “static” models because the former takes into account secondary effects of the tax change. In theory, they are quite right. Any change in tax policy typically has lots of secondary effects, and a competent modeler at least has to keep them in mind, and take them into account if they’re big enough. The kinds of dynamic tax models at issue here have been used widely in California since a law mandated them from 1996-2000. The record there was pretty mixed. A report by Jon Vasche, the director of Economics and Taxation in their state legislative research agency, pointed out these models didn’t do away with debate, and their results were “very sensitive to their underlying assumptions.”

And that’s the key: dynamic models are often just a convenient way to hide researcher biases behind technical snowdrifts few reporters can or will wade through. Issues like how many people move due to changes in tax rates or the sensitivity of investment decisions to economic conditions are the subject of ongoing research and debate. Hiding those issues allows model owners to assume the results they believe will be true without admitting that’s what they’re doing. It’s more elaborate to be sure, but no different from the butcher blocking your view of his thumb on the scale. Beacon Hill built a model that assumes the existence of a tax-cut fairy, and shockingly, the CFPMAP guys have found that model to show a sales tax cut would create an economic boom for Rhode Island. Who would have thought it?

In his landmark 1963 speech about the common strains among conservative movements in the US, historian Richard Hofstadter pointed out that certain elements of the right wing in America dote on the “apparatus of scholarship” even while they seemed to miss the point. Like the footnotes in that old OSPRI report, the CFPMAP authors use the apparatus of scholarship to mask partisan assumptions in the guise of documentation. Unfortunately, it’s not enough just to have footnotes and equations; it matters what they say.

Reports like these are little more than snares for gullible reporters. The strategy usually works: the snares get set, reporters step in them, and presto, the findings appear in news headlines and on talk shows. And then there are legislative commissions and hearings and pretty soon what seems like a crazy idea seems normal, and that’s the point.

Beyond the problem of defending our state against another bad idea, the real issue is that there is a moral dimension to lobbying. This is not a game. What happens up at the State House really matters. It is hardly unheard of for lives to be ruined and people to die because of bad decisions made there. Advocates, it seems to me, have a heavy responsibility to tread lightly on uncertain ice — someone might actually take their advice. The sales tax proposal on offer here invites us to stroll confidently out on that ice with nothing more than the CFPMAP’s word to say it will be safe. The question isn’t just would you take this advice, but with sourcing as thin and deliberately obfuscatory as this, would you feel good about giving it?