For most Rhode Island residents, plea bargains in criminal court are poorly understood. “They let him off easy,” some may say. Others may wonder why judges are not ordering the sentences unilaterally, and wonder why the defendant gets a say in the “bargain” process at all. The “If it bleeds, it leads” media have fed a culture of convictions, where criminals are “coddled” if getting nothing short of gruel before the lash. The inner workings of the system reveal that the bargain is generally for the sake of the State, not the defendant.

Providence Superior Court Judge Lanphear recently ruled that the prosecutors and defense attorneys must tell judges of all plea agreements, although the top judge (Presiding Judge Alice Gibney) stated that Lanphear’s ruling does not apply across the entire court system. What impact does that have on a defendant, the one who is afforded constitutional protections and attorney-client privileges?

How many past and potential defendants are in Rhode Island?

How many past and potential defendants are in Rhode Island?

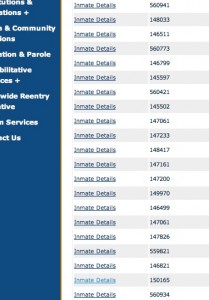

Not all criminal defendant’s pass through the Adult Correctional Institutions. Many will be arrested and released from the police station, so it is difficult to put a number on exactly how many people have been defendants in Rhode Island, a state of just one million people. The ACI has admitted over 150,000 people who were initially held without bail on a criminal charge. 90,000 of those people are over the past thirty years. But this is not all, because a decade ago the ACI began separately identifying people who were first admitted as probation violators; meaning, they had previously been arrested and convicted without having gone through the ACI. Now a subsequent issue (it could be a criminal allegation or as little as missing a meeting) has them being incarcerated. That tally is over 61,000.

Where 210,000 people hold unique prison identification numbers, perhaps the plea bargain is not so mysterious after all. Those people have families as well, so the number expands even further. Realistically, however, only a few thousand of those people really know how the “deal” works. The rest, as well as those of you not yet to get an ID number, might only figure it out when it is too late.

Having confidence, and confidentiality, with a lawyer.

Most defendants I’ve known don’t trust their lawyer, even the hired lawyers. This is not out of the norm with America’s disdain for lawyers, generally, despite continually electing them to political office. (Caveat: some of my best friends are lawyers.) I should point out that I’ve known thousands of defendants and served as a consultant on hundreds of cases for free. They trusted me because I had a reputation for confidentiality and nothing to gain, not a paycheck nor favor with my boss. Many defendants believe that a lawyer, whether privately retained or public defender, is just going through the motions. The defendant’s goal is to be in the “good” stack of people, those the lawyer “fights” for rather than those the lawyer “sells out.” They often believe a plea negotiation is “Listen, I’ll let you get this guy for twenty years but you gotta let these two guys get out on probation.”

Judge Lanphear is playing right into the conspiracy fears of defendants. He is making the attorneys into employees of the Court, rather than the client. The judge is adding extra players into the negotiation. Rather than parties A and B reach an agreement that C ratifies, he would like parties C and D to be privy for the ratification. Adding parties and expanding the morass to navigate will require more delays, status conferences, pretrial hearings, and time spent at the ACI. A 2012 legal victory in the U.S. Supreme Court held that defendants need to be told of all plea offers made by the government, ensuring full communication between attorney and client, but this is where the openness ends. An attorney has no duty, on behalf of a client, to inform judges (including Judge Lanphear) of a guilty plea in other courts. To hold those attorneys in contempt is to rewrite the code of ethics.

The Power of the Plea Bargain

People often forget that a defendant gives up quite a lot when pleading guilty, and provides significant relief to an overburdened criminal justice system. Judges and lawyers rarely mention the lifetime of discrimination (including legal restrictions) following a guilty plea, and rarely explain how easy it can be to fall within those 60,000 probation violators returning to the ACI- this time with practically no constitutional protections as the rules of evidence are far more lax and the burden of proof is merely based on a judge’s reasonable satisfaction that a probationer failed to keep the peace. Many times the only evidence comes from the arresting officer. It is for this reason we needed to amend the law so that people could not be violated and given prison time for charges that are ultimately dismissed. Of course the court, who years ago said “change the law,” are not satisfied the law was changed. Nor is the Attorney General, despite the fact that the predecessor who wrote the law supported the reform. (See: State v. Nelson, pending before the RI Supreme Court).

Defendants may eventually “crash the system,” when too many people refuse too many plea bargains. In New York City, for example, each of the 600,000 people who were infamously Stopped and Frisked by the NYPD, where no contraband was found, could have filed a harassment and/or civil rights complaint. The number of plaintiffs and cases were twice the 300,000 cases New York City courts initiated last year. The sheer volume would be a logistical nightmare, and the court would have begged them to consolidate into one single class action. That class action, coincidentally, proved victorious for the plaintiffs.

Defendants in Rhode Island have little faith in the system. Most of those who have done wrong are prepared to admit as much, which is one reason cases rarely go to trial. Prosecutors are even more overwhelmed than defense attorneys as police departments continue to funnel people into the ACI and the courts. Rhode Island public defenders have consistently had a policy of presenting several cases “ready for trial,” while the state then requests a continuance. A good attorney will speak with witnesses, review crime lab reports, and request court funds for expert witnesses. But rarely is that done on either side. It can all be avoided by going straight to “The Deal.”

Here is an example of The Deal, from State v. Isom, 62 A.3d 1120, 1123 (R.I. 2013):

“THE COURT: Okay. Thank you. Mr. Isom, did you have plenty of time to discuss this with your lawyer.

“THE DEFENDANT: Yes, ma’am.“THE COURT: And you understand that you have a right to the, a hearing on these violations?“THE DEFENDANT: Yes, ma’am.“THE COURT: And do you wish to give up your right to that hearing today and admit to the violations?“THE DEFENDANT: Yes, ma’am.“THE COURT: Okay. Understanding that you’re being sentenced to five years to serve on those violations, retroactive to the date of December 27th of last year?“THE DEFENDANT: Yes, ma’am.“THE COURT: Okay. Defendant admits and is declared to be a violator. That sentence just mentioned is imposed.“THE CLERK: Five years, is that coming off one of the specific cases * * *?“[THE PROSECUTOR]: That can come off of [the 2000 case], and that would leave a balance of eight years suspended with probation on that case. And the [2007] case may be continued on the same.“THE CLERK: Thank you

“THE COURT: All set.”

In this case, the Defendant returned to court because he mistakenly (yet reasonably) believed that the new allegations and the probation violation would be all “wrapped up” in one deal. That is the common practice, to wrap it up prior to the probation violation hearing that few (if any) defendants believe they can win- regardless of their innocence or guilt. He gave the system what it wanted, efficiency, in exchange for very little.

The longer a defendant is held without bail at the ACI, the more leverage against him or her to take the deal. The more suspended time looming over their heads, the more pressure to take the deal… or get slammed at the probation violation hearing. A defendant will often have two different judges: a Superior Court judge to oversee the felony arrest, and a District Court judge overseeing a lesser probation violation they face. Defendants may find themselves in front of one judge with the opportunity to “wrap it all up” within one deal. This saves everyone considerable time and money. Judge Lanphear is proposing to nullify that, creating more work and expending more time for everyone.

Will the System reform or collapse?

Those who read my blog know that I have a bias, but may also respect that I bluntly call it like it is. I have long felt that the demise of the criminal justice system as we know it will come if it collapses under its own weight. I do not foresee defendants taking collective action to crash the system, but they do not need to. The system already collectivizes their actions, as each unique identifying number requires judges, lawyers, bailiffs, clerks, sheriffs, marshals, police officers, and prison guards to process. Recent years have seen some take a reform approach due to the tax burden, changing attitudes on drug use, and cameras capturing abusive treatment that went disbelieved for far too long.

I wouldn’t read too much into Judge Lanphear’s ruling. When the rubber hits the road, including if his decision is reviewed by the Rhode Island Supreme Court, the system requires considerable latitude for negotiating the deal. It is a system that every Rhode Islander, based on the numbers, should be familiar with; someone in your family could be next.