When I moved to RI in 2003 from Washington, I was rather stunned to hear many of my liberal friends repeat the media meme that organized labor was too powerful in the Ocean State [note: I will use the term ‘liberal’ rather than ‘progressive,’ because in my experience people on the left my age and younger tend to substitute the latter for the former, without knowing the meaning of either].

When I moved to RI in 2003 from Washington, I was rather stunned to hear many of my liberal friends repeat the media meme that organized labor was too powerful in the Ocean State [note: I will use the term ‘liberal’ rather than ‘progressive,’ because in my experience people on the left my age and younger tend to substitute the latter for the former, without knowing the meaning of either].

My surprise stemmed from two sources: the extent to which liberals of my generation (I’m 45) underestimate the vital importance of unions for the enactment and preservation of liberal measures and attitudes, and the extent to which these same liberals had completely misread the situation in their own state.

On the latter, read Scott McKay’s brilliant take-down of the ‘union rules RI’ meme on NPR. As he notes, would the tax equity bill have gone down to defeat if unions truly ruled the roost?

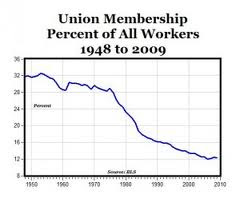

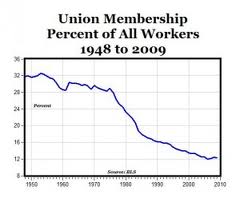

Just under 18% of Rhode Islanders are represented by labor unions; it was 26% in 1964, and 22.5% in 1984. In other words, the trend is the same here as everywhere: downward.

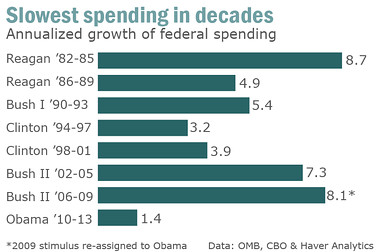

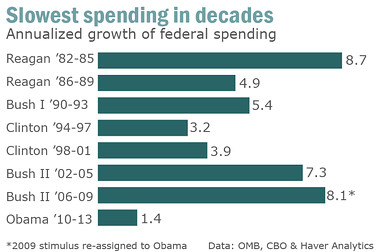

The national trend, since the passage of Taft-Hartley in 1947:

The breakdown by state, since 1964:

There are many reasons for this decline. Economic change, the shift of American industry and population to the South and Southwest, the restrictive nature of our labor laws, McCarthyism and red-baiting, poor and sometimes corrupt union leadership. Unions were also victims of their own success; by helping to create the post-war middle class, many of their white constituents (and their children) decamped for the suburbs, and resisted seeing the struggles of the black (and eventually, Latino) working class they left behind as similar to their own, rather than a threat. In other words, the American original sin of race infected — had long infected — even its most transformational social movements and institutions. Perhaps our individualistic and materialistic culture has also become indifferent — even hostile — to the sensibility of solidarity, upon which the labor movement depends.

All of these things have mattered, but the most important cause of labor’s decline, ultimately, has been the political success of corporate resistance, particularly since the early 1970s (on this, read Elizabeth Fones-Wolf and Jefferson Cowie, as well as Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson). Many of my peers (and my students) seem to assume that unions are a thing of the past, and that the victories they won — like the end of slavery and the enfranchisement of women — are now written in stone, and we can move on. In other words, progress gave rise to unions, and then tossed them on the scrap heap of history (with the American Anti-Slavery Society, The Women’s Party, the NAACP, and affirmative action) when they had fulfilled their role. Events in Wisconsin (and, of course, the Occupy movement) may have finally awoken at least some of these folks to the possibility that if the ship of history has moved in this direction, it may be because someone is steering it there.

As a labor historian and former organizer, I also had a hard time getting my head around the idea that unions could actually be too powerful — both because I can’t imagine that being the case anywhere in 21st America, and because I can’t imagine that being a negative thing, on balance. I would love to have to grapple with that problem, here and nationally.

Walter Reuther, vampire-killer…or life raft?

So why does the decline of labor matter, in Rhode Island and nationally?

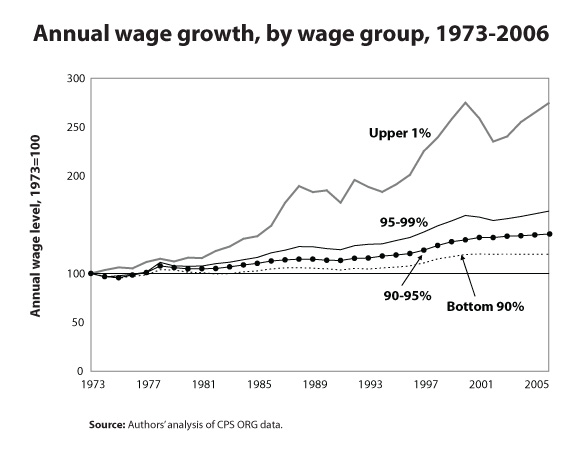

Well for one, it is hard not to be struck by the apparent correlation between the decline of union power, and the emergence of increasing inequality, economic insecurity, and wage stagnation for large portions of our population since the early 1970s. From 1940 until the early 70s, the economic benefits of the productivity of the American economy were widely shared, leading to what economists have called ‘the Great Convergence’: a shrinking of income inequality, combined with a strong and steady increase in the standard of living for the vast majority of the population.

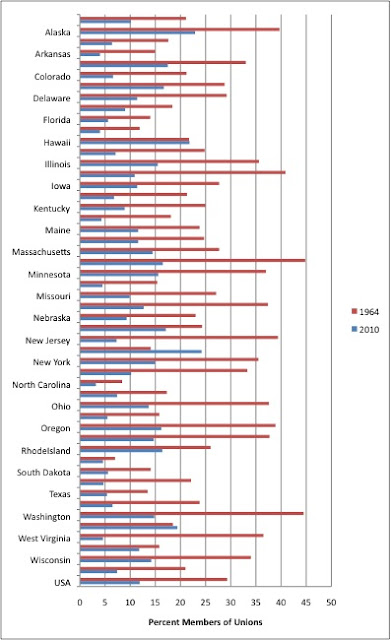

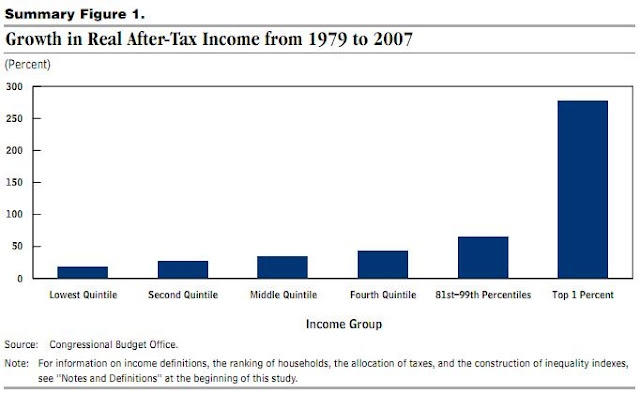

But since then?

So where did all that money go? Did it go to those wealth-sucking and budget-busting public employees that Scott Walker keeps going on about? Did those tax-and-spend liberals devour all of it, so they could rain manna on their special interest constituencies?

Um, no.

Is it any wonder why vampire stories seem to have captured the cultural zeitgeist?

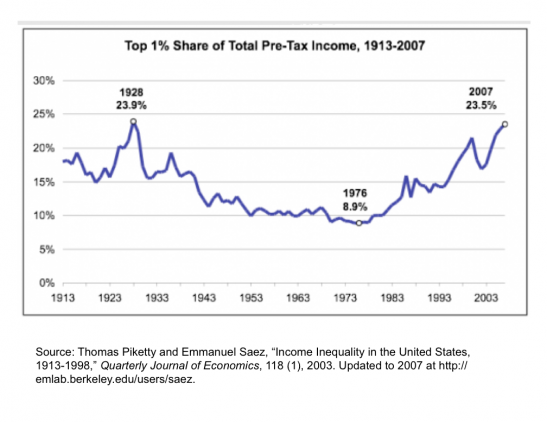

Here is a longer view, depicting both the Great Convergence (during which union density rose from below 10% to over 40%) and the Great Divergence. Note that the line on the right has moved further upward since 2007, to the highest point it has ever reached:

The inability of American workers to capture their fair share of the productivity of the economy since the early 1970s has very little to do with human capital. Why had they been able to capture it previously? Why have they struggled to do so since?

We are all grown-ups here; let us not be so naive as to think that the price of labor is actually and solely determined by supply and demand, and that if a worker ‘accepts’ a job at a particular wage, its because that’s the one she wanted/needed, or because its the only one the employer could afford to pay. I don’t live inside an economic model. And if I did, it surely wouldn’t be this one.

The Great Convergence was about power. And the Great Divergence is, too. American capitalists didn’t suddenly lose their moral bearings, and their interest in the rest of us (and, perhaps, their own souls — eye of the needle, and all that). Corporations seek profits. That’s what they are supposed to do. Unless you are a Marxist, that’s what you want them to do. They are good at it, and in the ugly process of pursuing their prey, they often do things that benefit others. But that isn’t the goal. Remember Aaron Feuerstein, the owner of Malden Mills in Lawrence MA? When his factory burned down in the early 90s, Feuerstein kept his entire workforce on the payroll until the mill had been rebuilt and reopened. An act of tzedakah, surely; but if Malden Mills had been publicly owned, his shareholders could have sued him — and won. People on the left just exhaust themselves trying to shame corporations into doing the right thing, and think that they are somehow offering a radical critique of our political economy by vilifying (and anthropomorphizing) corporations. But they aren’t. The only way to make our economic system compatible with the public good (and public goods) is to establish and maintain what John Kenneth Galbraith once called countervailing powers — institutions, in other words. Government, and unions, in other words. Without a strong regulatory state, a redistributive tax system that maintains social mobility, and real representation for workers, there is nothing standing between the sheep and the shears.

If we stick with the vampire analogy above, unions are like garlic. They don’t kill the vampires; they can still do their thing, and live for ever. But the garlic does keep them in their place, scares them a little, and prevents them from tearing our throats out. Nowadays, Republicans and many Democrats seem to assume that the vampires can do the cost-benefit analysis, and will take only what they need. And garlic is too expensive anyhow.

How is that working out?

Of course, this analogy has its flaws. Why not just kill all the vampires? Or perhaps those who are just too big to feed? Or maybe we can tax the vampires, to pay for the garlic?

Let’s try the rising tide analogy instead.

The top 1% making out like bandits might not matter to most of us, as long as the rising tide is lifting our boats too. I actually think it does matter, because inequality even within prosperous societies (indeed, especially within them) tends to have all sorts of negative effects on individual and social well-being. There is even some evidence that inequality hinders economic growth. But most Americans have never begrudged the rich their wealth. Plenty of folks got rich during the Great Convergence, and passed it on to their children. We don’t reshuffle the deck with each generation, after all. But the game never seemed rigged, at least to white Americans. They had unions, and their power at the bargaining table, and within the Democratic Party, ensuring wage growth tied to profits and productivity, job security, access to health care, and a humane retirement. Nationally, progressive taxation paid for both a safety net and a massive expansion in the infrastructure of public education (K-12, and higher education), providing opportunity for the next generation. There was, or at least appeared to be, social mobility.

The problem since the 1970s, of course, is that the rising tide has increasingly just left most of us wet. You can assume that the little green line on the right, below, dips down after 2008. Indeed, average hourly earnings were lower at the end of the first decade of the 21st century than they were at the beginning — and were lower than in 1972:

And when we put it all together, we get this:

Is the decline of organized labor responsible for all of this inequality? Of course not. Most scholars attribute between 20% and 30% of it to declining unionization — but those estimates are only based on the direct role of unions in labor markets, and thus underestimate the impact.

There is little doubt that weakened power for workers has affected wages, benefits and working conditions across large sectors of the economy, and for families and communities with no affiliation with (or affinity for) labor unions. Unions in a given industry have always raised the compensation levels for even non-union workers in the same industry. If that’s true, the reverse is also true. If employers no longer have to fear union campaigns (or the enforcement of already-weak labor laws), they can structure their workplaces with impunity. They have done so. Today, the middle class increasingly experiences the same sort of economic and job insecurity that the working class did a generation ago.

Another equally critical consequence of organized labor’s deterioration has been the decline in its political power, and its agenda- and narrative-shaping capabilities. The diminishing presence of labor’s perspective as well as its power no doubt contributed to the “policy drift” of which Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson have written. The problem, they argue, isn’t simply that government at all levels took steps that exacerbated inequalities and shifted risks onto working people, their families and their communities. That did happen, and the effects have been catastrophic. But these sins of commission were compounded by sins of omission too: Congressional and regulatory actions that might have been taken to shore up and even boost living standards and opportunities were not taken. Power can make things happen. Power can also prevent things from happening. Mainstream American political discourse was almost completely lacking in any kind of meaningful and widely heard critique of the neo-liberal agenda, until very recently. The DLC-dominated Democratic Party has been a vehicle for that agenda, not a critic of it.

Its the solidarity, stupid

People across the political spectrum are frustrated by the lack of any kind of countervailing power to that of capital (particularly financial capital). We don’t have a socialist or social democratic party in the US, unlike much of the rest of the developed world. And contrary to Tea Party fantasy, we don’t have a socialist president, either; after all, he swung and missed at the biggest eephus pitch since FDR’s first term, when he unwisely declined to use the federal government’s post-crisis leverage and break up the biggest banks.

As a result of this narrow political spectrum, there is very little pressure from inside our political system to create and maintain a broad distribution of the material conditions necessary for effective freedom in the modern world. When our uniquely American version of this countervailing power did exist — from roughly 1936 to 1972 — inequality shrank, social mobility increased, public goods were funded and widely distributed, the economy grew, productivity increased, and the nation finally grappled (however inadequately) with the legacy of slavery. And that countervailing power existed because the Democratic Party (outside the South) acknowledged the importance of seeding and nurturing the institutional roots of that power: unions. Indeed, some in the GOP even acknowledged this, though those folks are long gone now.

Conservatives today, ironically, offer only more insecurity. That is what Scott Walker is offering in Wisconsin, and what Paul Ryan (and Mitt Romney) are offering nationally. I say that this ‘offering’ is ironic, because there is very little that is conservative about it. Following Edmund Burke, conservatives have generally seen society as an inheritance that we receive, are responsible for, and have obligations to, and that if human beings seek to sharply change or redirect that society, they invite unintended and destructive consequences. In other words, what is and has gone before is by and large better than anything human beings might create in its place. Liberals, like John Stuart Mill, tend to see the societies and institutions into which we are born as human constructs, which can be unmade or remade in the light of reason. In this sense, American conservatism isn’t conservative at all, unless one wants to argue that all it is, in the end, is an ideological defense of privilege. Certainly its historical origins are in the defense of privilege, and the argument that inequalities are in some sense ‘natural’ or divinely ordained. After all, if today’s social inequalities were handed down by 1) God; 2) human nature; 3) the market), who are we to challenge or change them?

In another sense, as Mark Lilla has argued, we are all liberals in America today: “We take it for granted that we are born free, that we constitute society, it doesn’t constitute us and that together we legitimately govern ourselves.” Conservatives, in other words, have largely accepted the liberal argument for democracy that emerged out of the French Revolution — that the preservation of individual freedom requires political inclusion on an equal basis. For many American conservatives, particularly in the South, this is a very recent conversion; and as the state-level movement for voter ID laws makes clear, there is still a great deal of backsliding on the issue. The incarceration state that both liberals and conservatives have constructed in the last few decades has also disenfranchised millions of people, in most cases permanently. And because many conservatives are so prone to accept the legitimacy of ascriptive forms of solidarity, immigration tests their fealty to full popular sovereignty. To put it bluntly, the conservative commitment to full political equality is weak at best, and weaker still when the issue is race or national identity (or when vote suppression has partisan benefits).

But, for all that liberals and conservatives do have in common (with conservatives as reluctant junior partners in the larger project), they do still differ in their understanding of power, and of freedom. I was once a conservative; after all, I worked on behalf of William Buckley’s Young Americans for Freedom at the 1984 GOP convention. I was a conservative, because I thought freedom was the greatest American virtue, and that Communism and big government were the greatest threats to it. I still think freedom is the greatest American virtue, but now I have a more nuanced (and, i think, more accurate) understanding of its material and institutional preconditions in the modern world. Both liberals and conservatives are willing to tolerate various forms of inequality, and both generally adhere (at least in theory) to the belief that basic facial equality in law and politics cannot be compromised. But liberals also worry that social inequalities (income, gender, race, and increasingly sexual orientation), if left to fester and expand, will undermine political equality (and economic growth). Conservatives tend to see these social inequalities as the consequence of nature, culture, morality and effort — and even when they don’t, they worry that any attempt by government to ameliorate them will do more harm than good. My worries are now liberal worries, though what I seek to protect hasn’t changed since my YAF days.

I’m not sure I want to go so far as to say that liberals are now the true conservatives, though it seems that way at the moment. American liberalism is still a bit too attached to an ontological individualism for that to be true. It still holds too much to the idea that society “doesn’t constitute us,” which is surely incorrect, and leads Americans to a certain kind of blindness about morally unjustifiable inequalities (particularly with regard to race).

As I noted above, we do not restart the game with each generation. I think white Americans of modest privilege are particularly blind to this. When I ask white students in my classes on the history of race relations to tell me about how their whiteness has affected their lives, they stare vacantly into the middle distance for a brief moment, and then try to claim some sort of victimhood (‘the black students won’t let me sit with them!’), instead of trying to unpack their own privilege. Many white Americans today (left and right) cling so desperately to the idea that they have created all that they are and have, that when the persistence of racial inequality is pointed out to them, they condemn the messenger for racial divisiveness. Read this recent Wall Street Journal op-ed, for example, which condemns Attorney General Eric Holder for pointing out that voter ID laws will have a racially disproportionate impact, and that in some places, that impact may have been intentional (Really?). Of course, Americans with even more privilege often react the same way when economic inequality is pointed out to them. The wages of whiteness do still pay, but not nearly as well as stock options, bank bonuses and trust funds do. Ignorance of the former breeds ignorance of the latter, even among liberals, until the idea that society ‘doesn’t constitute us’ is re-examined. As Thomas Geoghegan has argued, post-60s liberals and Reagan conservatives — and even the left, such as it is — seem to share the same Emersonian individualistic conceits. They have the sensibility of scabs.

But as we move toward a more Green Liberalism (is that what we should call it?), I think the traditional liberal/conservative lines will blur. The potential common ground will ultimately rest upon a solidaristic recognition of contingency, and human interdependence. This recognition is, I think, a fundamentally conservative one. And I’m OK with that. What is sustainability, after all, if not a fundamentally conservative concept? There is, of course, an available and very powerful conservative critique of the excesses of capitalism (and capitalists), but it has no purchase anywhere on the American right anymore, theologically or otherwise. Solidarity for the American right seems to be entirely ascriptive nowadays, as the insecure white middle and working classes run to the barricades to defend the very economic ideologies which are stressing their families, weakening their communities, bankrupting their country, and poisoning their trust in political and social institutions. The virtue of solidarity for the left was always learned in and articulated by the labor movement (and, to an extent, the church and synagogue). Where is it supposed to come from now?

A revived labor movement, that’s where. My lefty friends, the path to sustainability starts with solidarity. And solidarity starts by once again empowering Americans to collectively represent themselves at their work places. Geoghegan wrote about this two decades ago, and Richard Kahlenberg has taken up the cudgel more recently: the right to join a union is a basic civil right, and should be treated as such.

Geoghegan:

“I can think of nothing, no law, no civil rights act, that would radicalize this country more, democratize it more, and also revive the Democratic Party, than to make this one tiny change in the law: to let people join unions if they like, freely and without coercion, without threat of being fired, just as people are permitted to do in Europe and Canada.”

Yes.

Now, of course, we must play defense (Wisconsin). The evisceration of collective bargaining rights is not only a violation of a basic and internationally recognized human right (see Article 23 of the U.N. Declaration of Human Rights). It also threatens to destroy — perhaps permanently — the delicate balance between capitalism and democracy that Americans have struggled to establish since the Civil War. Contrary to the arguments of Scott Walker and others, the winner will not be the economy, or government budgets. The winner won’t even be capitalism, which will ultimately be undermined and delegitimized by the present trend, much as it was during the Great Depression. The lesson of the economic and political history of the developed world since World War II, quite simply, is that without some sort of institutionalized mechanism of countervailing power to that of capital, the liberal democratic mixed economy that has lifted so much of the human race out of perpetual misery will be in mortal danger.

‘Interdependence’ has become a truism these days, trumpeted equally loudly by those who believe that economic globalization will save the world, and those who believe it will make it uninhabitable. But there is little doubt that both experience and empiricism tell us that for each to rise, we must in some ways converge. As the epidemiological studies of Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett have shown, the more unequal a society is, the less healthy and happy it is for everyone in it. Inequality affects our health, our communities, our susceptibility to violence, our sense of social belonging and political efficacy, and the well being of our children. Studies of early childhood and cognitive development have provided empirical proof for many of philosopher John Rawls’ arguments about the extent to which even seemingly ‘innate’ inequalities of talent and effort are constructed by and derived from circumstances outside of us.

We are, in other words, constitutive of one another to a degree that most Americans might find unnerving to acknowledge. More broadly, there is so much about us that is situational, contextual, and contingent — the ethos of possessive individualism which has so dominated the American mind for much of our history is, quite simply, an unsustainable conceit that we can no longer afford. It is not rooted in ‘human nature.’ For most of our (pre)history, cooperation has been far more functional socially and individually than competition has been. That remains the case.

Individualism, as the old union saying goes, is for scabs.

The essential virtue of the 21st century, I believe, is empathy — which I take to mean, the implicit recognition of interdependence. The civic manifestation of empathy is solidarity. And solidarity can take many forms. It can be a kind of ‘ascriptive solidarity,’ defensively assembled along the socially constructed lines of race, language, and faith. There is a long history of this in our country — what Gary Gerstle once called ‘racial nationalism’ — and it persists strongly in the present. But solidarity can also be rooted in an inclusive acknowledgement of human interdependence. Virtually everything that liberals want to see in the world — indeed, what many conservatives want to see too — ultimately returns to the need for solidarity. If that solidarity is to be of the inclusive rather than the ascriptive kind, to be blunt, we need unions. As Geoghegan argued in his classic book “Which Side Are You On,” it was this idea of solidarity that always made unions so oppositional in the US, even when the 60s New Left naively dismissed them as part of the Establishment. When we lose the labor movement, we endanger that sense of social solidarity, upon which so much of what works in our way of life depends. The virtue of empathy, perhaps, requires good people — individuals making the choice to be empathetic. Solidarity, however, requires institutions within and through which people can practice that virtue. As Aristotle argued, in order to be a virtuous (empathetic) person, one must do empathetic acts. But as I’ve argued above (and as Rawls argued in Theory of Justice), we need the institutional framework of our society to be just, if this is to happen. The most important institution for this is liberal democratic government itself. But as long as we choose to pair that institution with an economic system organized around markets and commodities, which inherently twists, dissolves and melts empathy and solidarity into atomized air, and which treats every American worker as ‘at will’ (you can be fired for virtually any reason at all, or no reason), unions will be necessary.

In the summer of 1934, after a wave of union organizing and localized general strikes had swept the country, President Franklin Roosevelt took a trip to Madison, Wisconsin. While there, he called for a politics of solidarity that “recognizes that man is indeed his brother’s keeper, insists that the laborer is worthy of his hire, [and] demands that justice shall rule the mighty as well as the weak.”

77 years later, a protestor held up a sign in that same city: “SCREW US, WE MULTIPLY.”

So there, Scott Walker.