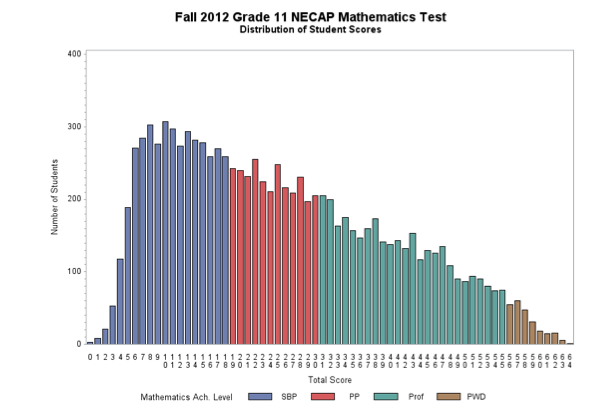

Now that we are in the period of NECAP retesting for seniors who failed the test as juniors, it would be good to take a look at how the math test is constructed. Because that, after all, is the test most juniors failed in the first place. In the chart below you can see how students did, item-by-item, when they took the NECAP grade 11 math test in 2012.

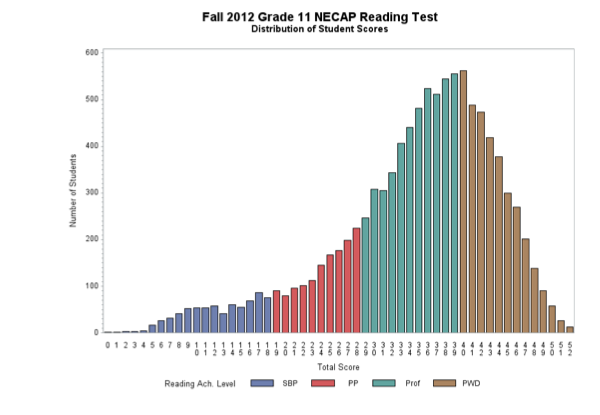

The thing that shoots off the page is that the curve shown in the chart doesn’t look much like a normal curve. If you remember, a normal curve is described as a “bell shaped curve”, meaning it is symmetrical, highest in the middle, and slopes downward to the right and left. To see a bell curve, look at the reading test results shown below the math test: it’s not a perfect curve, being squished a little on the left, but at least it’s some version of a normal curve.

What we see above is definitely not symmetrical, nor does is slope downward to the right and to the left—to the right, yes, there is a long, straight slope, but to the left there is a precipitous drop. Altogether, it looks like a wedge with its thin edge to the right.

What does a wedge shape mean to a student taking the test? The numbers below the bars tell you how many students got a particular item correct and you can see that very few students only got item “1” correct. But thereafter, things change dramatically and the numbers of students getting very low numbers of items correct stacks up like 95 at rush hour. In fact, in the math test, the scores the most students got were between 7 and 11 items correct—out of a possible 64! More than 300 students only got 9 items correct.

What this tells us is that the math test has no lead-up of items that gradually get more difficult. Instead, it begins with difficult items and then makes each item more difficult, which accounts for the almost straight line of descending scores to the right. This design—hard items and then harder items—makes it difficult for students to do better without putting big resources into remediation efforts of doubtful long- term value.

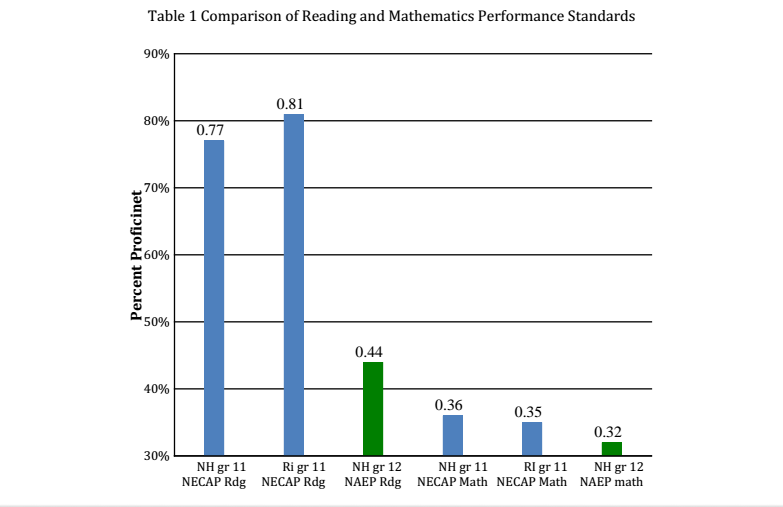

Defenders of the NECAP math test say the problem is not the test but the education system—bad teachers, essentially. Part of their defense rests on showing questions that students who fail the test get wrong. Adults who see these items tend to solve them and think that of course most students should get them right. But this is a bogus exercise–the adults who see these items are never in the pressurized testing environment where students encounter them, so it should not be taken seriously as a defense of the math test.

Instead, look at the reading test, shown below. It’s hard to look at the two graphs and believe the reading and math test are constructed using the same design. In the reading test, the long tail to the left indicates a run-up of easier questions and, in this situation, improving performance between tests would be a much less difficult task. The remediation might not be any more educationally meaningful, but there would be less of it, it would be less difficult to provide, and it would divert much less time, energy and money. Indeed, that is what happened.