If there is one thing a documentary film should strive for, it is exposing people to a little-known aspect of life. This is precisely what filmmaker Edgar Barens has done with his Oscar nominated film, “Prison Terminal: The Last Days of Private Jack Hall.” It premieres on HBO, on March 31st, and is poised to stir up some substantial changes in America, the global incarceration leader, where approximately 250,000 aging people are behind bars.

If there is one thing a documentary film should strive for, it is exposing people to a little-known aspect of life. This is precisely what filmmaker Edgar Barens has done with his Oscar nominated film, “Prison Terminal: The Last Days of Private Jack Hall.” It premieres on HBO, on March 31st, and is poised to stir up some substantial changes in America, the global incarceration leader, where approximately 250,000 aging people are behind bars.

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, between 2001 and 2011, cancer and heart disease were the leading causes of over 3,000 annual deaths in state prisons. Another 1000 people die every year in local jails, often with little or no health care.

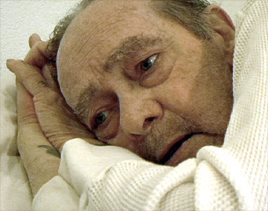

I met Edgar Barens in 2009, when he had 300 hours of footage from the Iowa State Penitentiary’s hospice unit, shot over six months in 2006-2007. Prison administrators invited him to do a story after seeing his previous documentary Angola Prison Hospice. This latest product is a 40-minute film nominated for an Academy Award. Coincidentally, Prison Terminal is about the death of Jack Hall, a World War II POW survivor, while the winning film was about the last survivor of the Holocaust.

Jack Hall is proud of his military service, yet remains haunted by the hundreds of farm boys, tradesmen, and regular folks he killed while wearing the uniform. It is interesting that the government awarded medals for these killings, but sentenced him to die in prison for killing the man who sold drugs to his son. The latter was probably the only time he had a genuine motivation to end someone’s life, but Jack’s story here is not about that homicide. The story is deeper, taking us to a crossroad of multiple dilemmas in America’s criminal justice system.

The Disposable Heroes

Incarcerated veterans are vastly growing in number, as they historically do after every war, with estimates ranging from 140,000 to 250,000 currently behind bars. It should come as no surprise that Jack Hall’s experience of killing, seeing friends die, and being held in an enemy prison might leave more than a few scars. It is understandable that any such person might seek to suppress their thoughts with alcohol or drugs, and may also have a hard time holding down a regular job. This PTSD and effects, and effects of effects, helps explain the record high disposable heroes currently locked up in prison after their Iraq and/or Afghanistan tours. It is only amplified by America’s shortcomings in soldier reentry and rehabilitation (words typically used for prisoners returning home, but soldiers’ experiences can be frighteningly similar).

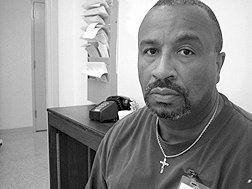

At the heart of Prison Terminal is a hospice program, where fellow inmates are serving as the volunteers and providing end-of-life care. In another twist on presumptions, Jack is a former Segregationist who found himself living in the most intense racial experiment throughout history. The viewer doesn’t experience Jack’s evolution over the previous years, but what we see is the shared love and humility of two primary caretakers in action: “Herky,” and “Love,” both Black men. Both also convicted of killing someone and will apparently also die behind bars. As they see it, what they do for Jack will hopefully be done for them when the time comes.

Many members of the general public develop their views of prisons through television shows such as Oz, Orange Is The New Black, and LockUp. Furthermore, most documentaries focus on a wronged situation, such as exonerations, drug war casualties, and political prisoners. Prison Terminal defies stereotypes and presents a familiar world to those who have been incarcerated, and their families. Herky and Love are like hundreds of people I know: just waiting for a burning car on the side of the road so they can save some kids. It will never erase the terrible things that gets someone into prison, but will at least make looking in the mirror a little easier by creating a counter-narrative, about helping humanity rather than hurting. Not to imply that everyone in prison is an angel, nor even that the majority are there for something terrible, but the number of lifelong malicious and selfish people in prisons is a far smaller than most would ever imagine.

It should not come as a massive surprise that the majority of hospice workers in Iowa are Black. As examined in the book, “Mothering in Prison,” some communities unfortunately have learned to expect travesties. Coming up out of slavery and through a challenging American history, Black people have had to adapt to survive, and take care of their wounded family. Here, Jack Hall is part of this family regardless of his color. And to Jack’s credit, healing his previously-strained relationship with the son who turned him in is a core part of the dying process.

Prisoner health care: an oxymoron

Prison health care in America primarily consists of popping pills, and scant staffs struggling with sparse budgets. If they are going to take control of someone’s body, the government has a legal and moral duty to take care of it. However, not every person enters prison with a clean bill of health. They go in with cancer, diabetes, HIV, and every other ailment afflicting the general public. Perhaps on the outside they had a job, insurance, or even coverage under the Affordable Care Act. And then they are sent into this jungle. The diet is terrible and, at times, the exercise non-existent. Leave someone in prison long enough and they will certainly contract any ailment one would expect on the outside.

There are only 75 hospices in the thousands of American jails and prisons, and only 20 are staffed with prisoner volunteers. People should die with their families, especially the ones closest to their hearts. Iowa’s hospice program struggled since the film was made, as a new director was not as passionate about the program. This signals the need for specific policies to be in place, to survive turnover and attitude. The program costs absolutely nothing, with everything donated (including hospital beds) or made by prisoners. Hospice actually saves money by weaning people off costly medications and treatments in their final days.

Some states have responded to the medical crisis by building multi-million dollar medical facilities that will need to be staffed and maintained over the years. This also creates more overall beds in the system; beds to be filled. Every prison should instead convert space already in place, and consider Medical Parole whenever possible. Not everyone has somewhere to go in the final years, and granting homelessness to sick people is not providing dignified deaths.

Edgar Barens is taking Prison Terminal on a tour that will include dozens of prisons throughout the nation. This film should be seen. A five-minute version should be screened for politicians. Hopefully they, like Iowa, will recognize that it is possible to do better. They can respect families and religions, and make a considerable reform within this terrible phenomenon of mass incarceration. Furthermore, the Veterans Affairs administrators can watch this film and reconsider the final crime in Jack’s case: the VA would not allow him to be buried with honors due to the “Timothy McVeigh” rule, barring people convicted of capital crimes from a final acknowledgment of their service. Jack’s final respite, despite fears his service would send him to Hell, was to be buried as a soldier. Instead, the prison fingerprinted and disposed of him, his life, and death.

Pvt. Jack Hall escaped from a POW camp, yet could not escape that one moment of rage as an unwilling soldier in the War on Drugs.

Find out more at www.prisonterminal.com.