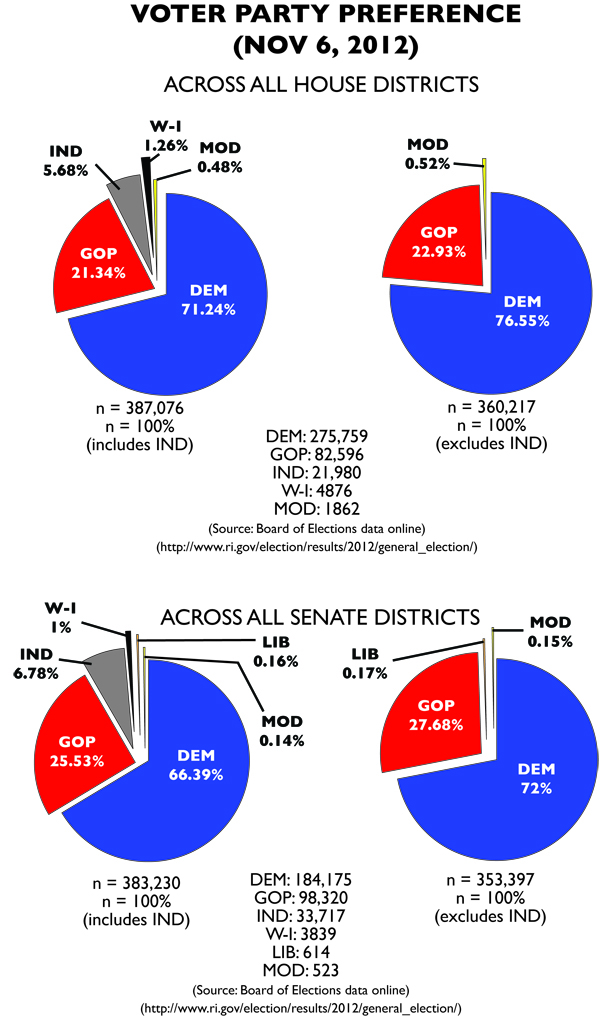

Nationally, Barack Obama was campaigning for a second term. Democrats were convinced they would win, while Republicans were convinced they would win. While Rhode Island was a sure thing, the chance to vote for President increased turnout to historic proportions.

This was bad news for the Republicans and Moderates in the General Assembly. Democratic voters completely overwhelmed their candidates, and many General Assembly candidates never faced opposition in the general election. State Republican Party chairman Mark Zaccaria’s “quality over quantity” strategy was especially foolish in this environment. Republicans actually lost votes from 2010, as many voters were denied the ability to select a Republican for General Assembly at the polls.

The Moderates were unable to hang on to their two seats. Though they finally contested the Senate, they pulled fewer votes than in 2010, and the Democratic tide significantly increased the hurdle to receive seats under the apportionment method. They were less successful than the Green Party had been in 2004, and the Greens lacked the institutional advantage of being a recognized party.

Democrats also avoided a repeat of the Montalbano episode in the House, as Speaker Gordon Fox held off independent challenger Mark Binder. Fox would now preside over a delegation of 109 Democrats, while his Senate counterpart President M. Teresa Paiva Weed would have 55 Democrats. Once again, the Democratic Party had its veto-proof supermajority.

Implications

2012 burst the Republican balloon, especially after conservative media predicted a blowout for Mitt Romney. National Republican obstinacy seems like it may have convinced a large number of Democrats that it’s not a safe thing to stay home. The other thing is that 2012 brought Democratic voters out at levels about what one would expect in a presidential election year. But Republican voters appear at rates just slightly better than 2006; their worst election.

Part of this really is attributable to the lack of competition. As I’ve said before, challenger apathy effects both sides roughly equally, with an advantage going to Senate Democrats. Zaccaria’s strategy of not spending resources on races Republicans can’t win sort of ignores the fact that there’s really little data about what races Republicans can win that they don’t already have a solid lock on. Senate Minority Leader Dennis Algiere regularly racks up around 11,000 votes in his usually uncontested general elections, making him one of the Senate’s highest vote-getters. House swing districts like 71 and 72 (held by right-wingers Dan Gordon and Dan Reilly, respectively) returned lefty Democrats in 2012; in the case of 71, Republicans failed to even put up a challenger.

In an MMP election where the district results are tied to your party’s seat total, failing to run candidates can have a very disastrous effect. A few hundred write-in votes are nothing compared to the huge amount of votes incumbents get. In a purely FPTP system like we have now, it also deprives Republicans of the ability to point out how popular their ideas are statewide. Part of this is because their ideas really aren’t so popular. In this case, it’s actually better for Republican self-image to automatically lose a third of all races and then complain about voters voting for Democrats. In far too many races, voters didn’t have a choice.

This is Part 9 of the MMP RI series, which posits what Rhode Island’s political landscape would look like if we had switched to a mixed-member proportional representation (MMP) system in 2002. Part 8 (the Election of 2010) is available here. Part 10 is a look at the limitations of this series.