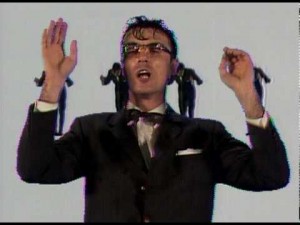

Former Talking Heads frontman David Byrne’s recent article in the Guardian lamenting the impact of streaming services like Spotify has appeared one too many times on my social media timelines to spare you all the following rant. In brief, the piece reveals Byrne as a one-percenter with no real sense of the lives and needs of the 99 percent of musicians and artists in the US.

Former Talking Heads frontman David Byrne’s recent article in the Guardian lamenting the impact of streaming services like Spotify has appeared one too many times on my social media timelines to spare you all the following rant. In brief, the piece reveals Byrne as a one-percenter with no real sense of the lives and needs of the 99 percent of musicians and artists in the US.

No, I won’t be making the obvious you-kids-get-off-my-lawn argument. Too easy. Nor will I discuss the qualities of Byrne’s music that might make him concerned about his earning power as he ages.

Rather, this essay discusses copyright laws, the structure of the music industry at various levels and how David Byrne’s zero-point-one percent problem is the desirable outcome of the largely democratizing impact of the Internet on the musical arts. As I often try to do, I’ll add a punchline.

The Talking Heads Catalog Should be Free

Early in the article, Byrne announces that he’s removed as much of his catalog as he can from streaming services. If I were a cynical PR hack, I might think that this article was an explanation to his fan base about why they might not be able to get Artists Only on Spotify anymore. This, in and of itself, is a one percent give-away.

Surely, it’s the Talking Heads catalog and not his later solo work that is streaming at high levels and, as he sees it, depriving him of his deserved revenues. He can thank two extreme conservatives for the privilege of making this argument: Walt Disney and Sonny Bono.

According to the Statute of Anne, the English law from 1710 that is the basis of modern copyright law, all Talking Heads music published before 1985, essentially all of it, would today be in the public domain. The Statute of Anne provided 14 years copyright protection from the time of creation, with an additional 14-year extension if the creator is still alive. 77 + 28 = 105, thus the first Talking Heads record released in 1977 would have entered the public domain around 2005. All the good stuff – the Eno stuff – would be free.

As material in the public sector, these songs could freely be played, covered, added to, sampled, etc., and one could argue that it would keep Talking Heads music a relevant part of the ongoing artistic conversation. Instead, assuming that various composers live past 2030 (just 17 years from now), then this music will not enter the public domain until the late 21st or early 22nd century, depending on authorship. Thanks to the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act of 1998, protections last 70 years after the death of the creator or 95 years from publication for corporate (group) creators.

So marking the 22nd century as the next time Talking Heads music will be a relevant part of the artistic conversation assumes, probably wrongly, that Congress won’t extend the term again as we approach the magic 70 years after Walt Disney’s death. That’s 2036, if you’re keeping score at home.

The new and radically progressive English parliament created the Statute of Anne to encourage creators to create, to provide a financial incentive for them and not the publishers, who tended to censor the content available to the public. Thus the limited term sought to reward creators for a reasonable period and then allow the public free access to do with the material what they would. In this regard, it is one of the most progressive laws ever created.

The framers of the Constitution patterned US copyright law on the Statute of Anne, enshrining in the Constitution that copyright would be for a “limited period.” Legend is that Rep. Sonny Bono (R-CA) once argued that copyright should be forever. When informed that this was unconstitutional, he suggested that it be “forever minus one day.”

As it stands today in the US, publishers enjoy nearly complete control over the material available to the public. Or they did, until the Internet happened.

“Because a Record Label Believed in Us”

“I can’t deny that label support gave me a leg up,” Byrne states, while simultaneously admitting that it’s not a requirement. Indeed, Metallica – one of the biggest Internet haters of all – grew their fan base organically with live performances and self-produced records sold by mail-order. Granted, Metallica was a heavy-metal band back then, so it’s apples-and-oranges. But I digress.

Byrne argues rightly that services like Pandora and Spotify make most of their payouts to record labels and that the labels usually keep most of this for themselves. What he doesn’t say is that this is no different from any other kind of sale of label-managed music. From the dawn of the industry, most publishers have taken advantage of desperate and/or poorly-informed artists.

In all likelihood, Byrne was one of these. When Byrne talks about pulling as much of his catalog as he can, he intimates that some of the material – most likely the early and high-quality TH material – is out of his and probably the other band members’ control. Its the most common trick in the record label book to give artists a big advance with an unrealistically short repayment window so that they forfeit their rights for non-payment.

Labels are similarly famous for not paying artists according to contracts. I heard a story once of a CPA in LA who specialized in auditing record labels on behalf of artists. After hundreds of audits over more than a decade, he found zero instances where labels had fairly compensated artists. Not a single one.

One might wonder if Byrne is under a gag order not to defame his current or past labels, but only Byrne, the labels and the NSA know for sure.

Byrne makes passing allusions to things like live performances and sales of non-music items like t-shirts, but the basic premise of his article is that musical artists generate the majority of their income from sales of recordings. This is the one percent give-away. In fact, it’s more likely that just one tenth of one percent of musical artists make the majority of their income from recordings. As a local reference, Deer Tick would likely be in this group.

The second zero-point-nine percent cobble together income from small-venue performances and merchandise sales to make such meager existence as they can. The Low Anthem, whom I’ve come to know to some extent recently, are signed to a significant label – Nonesuch. But they are in this second point-nine percent, needing strong performance revenue to make ends meet.

The 99 percent of musicians have other jobs. Even a band as apparently successful as Roz Raskin and the Rice Cakes all have jobs. I know this because I patronize the shop where Roz and drummer Casey work. (Magma video…teh awesome.)

Technology and the Democratization of Music

So where is Mr. Byrne on these issues? 1977, apparently. The reason that fewer and fewer musicians make significant revenue from recordings is not the Internet itself; it’s the value of recorded music, which is significantly lower than it was before two key technological changes altered the equation.

At $0.99, the price of a “single” recording is lower than it was. But that lower price is due to an enormously expanded supply of such recordings.

When the labels could control what and how much music the public could access, they did so by virtue of the high costs of creating a recording and the significant logistical challenges of distributing that recording on even a regional basis. Under such an arrangement, signed artists like Byrne could benefit greatly, if they were savvy enough to protect their interests. The 99.9 percent had to keep their day jobs.

Since 1977, that second point-nine percent has entered the market, increasing by 900% (assuming these rough estimates) the number of options available to the music consumer. It’s supply-and-demand revolution, enabled by the combination of cheap, high-quality recording technology and free/freemium, Internet-based distribution outlets like Bandcamp, Soundcloud and Spotify. As an added benefit, it eliminated the labels from the equation.

Thus, for 90% of the content providers that use them, these streaming services act as their primary marketing vehicle to drive sales at their live shows. This, Mr. Byrne, is the modern music industry for almost everybody. You and the people you know are the elite.

Where are you, Mr. Byrne, on issues like universal health care that would make it so that we wouldn’t need to hold charity drives when one of our own gets leukemia? Where are you, Mr. Byrne, on the issue of living wage, which would make it possible for a person to have a decent half-time job that provides subsistence such that they could play music as a second career? Where are you, Mr. Byrne, on cutting back on the outrageous copyright laws that enable the tyranny of the labels against which you rail so meekly.

Oh, that’s right…you’re not a US citizen. (I should note that Byrne’s native UK government went even farther than the US government in its most recent copyright shenanigans, actually reinstating copyrights and thus removing material from the public domain. This villainy shames the parliamentary institution as nothing else can. Queen Anne would puke.)

And the Punch Line…

Byrne’s previous article in the Guardian…?

“If the 1% stifles New York’s creative talent, I’m out of here.“

Here’s your coat. What’s your hurry?