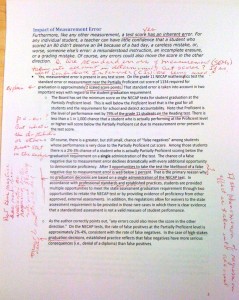

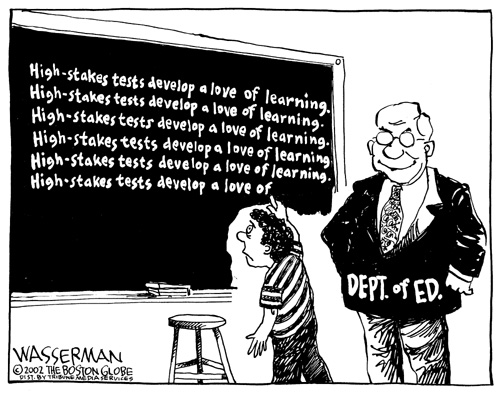

If I had to pick one thing to complain about with the high-stakes NECAP testing regime it wouldn’t be the pressure on the students, the deformation of the curriculum, or any of that. If it was just one thing, it wouldn’t even be the misguided policy to use NECAP as a graduation test. It would be that RIDE policies have taken a tool they could be using to understand what’s going on in our schools and deformed it so it can never be useful for its intended purpose.

If I had to pick one thing to complain about with the high-stakes NECAP testing regime it wouldn’t be the pressure on the students, the deformation of the curriculum, or any of that. If it was just one thing, it wouldn’t even be the misguided policy to use NECAP as a graduation test. It would be that RIDE policies have taken a tool they could be using to understand what’s going on in our schools and deformed it so it can never be useful for its intended purpose.

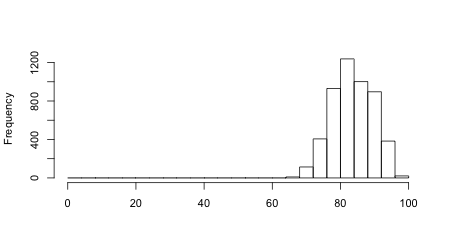

What’s the problem? Just this: the NECAP test was intended to gather data about our schools, but the high stakes — teacher evaluations, potential school closings, high-school graduations that all depend on NECAP scores — have guaranteed the data we get from the test are not trustworthy. It has been turned from a useful tool to a gargantuan waste.

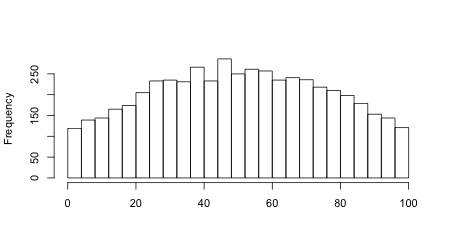

As any scientist knows, it’s hard to measure something without affecting it. But if you affect it, then what have you measured? So you measure gently. If you really want a measurement of how a school is doing, a sensible testing regimen would at least try to be minimally intrusive. Testing would be quick and not disruptive. Test results might be used to monitor the condition of schools, teachers, and students, but important decisions about them would depend heavily on subsequent inquiry.

The NECAP test itself is more intrusive than is ideal, but it could easily meet these other conditions, if scores were kept quiet and not directly tied to any sanction or punishment. The federal NAEP tests are like this, and they provide good data in no small part because there’s no incentive to push scores up or down. By contrast, the state Department of Education trumpets school scores, encourages school departments to adjust curricula to game the test designers’ strategy, and creates the conditions that virtually ensure that some school administrators and teachers will at least consider ways to cheat on the test.

To be completely clear, I know of no evidence at all that any teacher or administrator in Rhode Island has cheated on the NECAP tests. However, though it’s hard to find cheating, it’s easy to identify incentives to cheat. In a climate where professional advancement or even keeping one’s job as a teacher or principal requires improvement every single year (no matter how good you are already) the incentives are obvious. And in school system after school system, across our country, similar incentives have led to completely predictable action.

Lately, we’re hearing from Atlanta, where the former superintendent — the 2009 superintendent of the year of the American Association of School Administrators — and 45 principals and teachers are now under indictment for orchestrating a huge conspiracy that apparently involved locked rooms full of teachers pressured into “correcting” student tests and administrators wearing gloves while handling doctored test papers. But before Atlanta, we heard about DC schools. Before that, there were similar scandals in Texas, Maryland, Kentucky, Wyoming, Arizona, North Carolina, Illinois, Florida, Wisconsin, Louisiana, Connecticut, California, Michigan, Virginia, Utah, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Nevada, Kansas, New Mexico, Tennessee, New York, and Massachusetts. This list doesn’t count all the mini-scandals that might have just been misunderstandings about test procedures, or maybe weren’t.

This is hardly all. Last year, when the Atlanta scandal broke, reporters at the Atlanta Journal-Constitution surveyed testing data from a few thousand school districts around the country last year, and found 196 of them showed statistical inconsistencies similar to the ones that led to the Atlanta investigation. That doesn’t exactly imply that Atlanta is an exception.

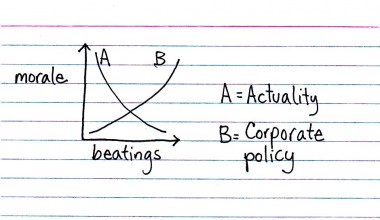

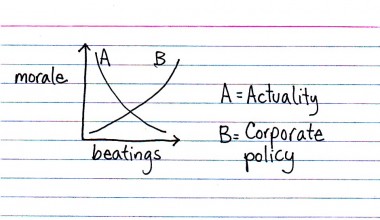

Predictably, the policy responses to these scandals have been simply to tighten security requirements, not to rethink the testing policy. Unfortunately, it’s not as if this is new territory. Let me acquaint you with an observation made by Donald Campbell, a past president of the American Psychological Association. He published an article about measuring the effects of public policy in 1976 that stated what has come to be known as “Campbell’s Law”: “The more any quantitative social indicator is used for social decisionmaking, the more subject it will be to corruption pressures and the more apt it will be to distort and corrupt the social processes it is intended to monitor.”

He wasn’t the only one to notice this. A banker named Charles Goodhart made the same observation around the same time, as did anthropologist Marilyn Strathern who put it succinctly: “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” Cheating on high-stakes tests is only one manifestation of this. You saw the same thing when Barclays and UBS conspired to rig the LIBOR interest rate (an index rate meant to be a market indicator), or when stock prices become the focus of company policy rather than just a measure of how they were doing. Enron became (in)famous for this, but they were far from unique. If you want to read a detailed (and uncharacteristically entertaining for an academic) account of how the principle affects testing, try “The Inevitable Corruption of Indicators and Educators Through High-Stakes Testing” by researchers at the University of Texas and Arizona State. (Where I ran across that list of testing scandals above.)

All of these are observations about how the world actually works. ignoring them won’t change them. You might complain that if Campbell’s Law is true then we can’t use testing as a valid measure of teaching and then where’s the accountability. Sadly for you, your complaint won’t change the world to something you prefer. This gets to a fundamental distinction between sensible policy and the other kind. Sensible public policy takes the actual, real, world — the one that you and I live in — and finds ways to work within the contraints of reality, be it physical, psychological, economic, or diplomatic. The other kind posits a world as the policy maker would wish it to be and careens forward regardless of the consequences.

In other words, if we know that applying high stakes to a test distorts the data we get from that test, then sensible policy dictates that we don’t use it that way. There are lots of creative and intelligent people out there capable of finding ways to use the valuable information this test could have provided in constructive and useful ways. But that’s not the way we’ve played it.

So here in Rhode Island, we now have the worst of both worlds: a test that can no longer do what it was designed for, while at the same time it has a deeply destructive effect on students, teachers, and the curriculum. Plus it costs millions of dollars to develop and administer, not to mention lost instruction time and wounded lives. Congratulations.