Once again, the RI Department of Education has amended its graduation requirements on the fly, surprising districts and education observers with broadly-expanded parameters for the granting of “waivers,” or ex post facto exemptions from the controversial high-stakes testing requirement. The changes made front page news, and rightly so: with 4000 students’ diplomas at stake this year—and presumably a similar number at stake every following year in perpetuity—RIDE had little choice but to either severely amend the requirement or face a renewed firestorm of opposition from both persistent advocates like the Providence Student Union (disclosure: I am a staff organizer for PSU), and also parents from suburban and more affluent communities whose children had come face-to-face with the unforgiving nature of standardized testing.

However, I fear that discussion on the expanded waiver parameters has ignored its most radical component. Thus far, public attention has focused almost exclusively on a provision called “batch approval.” Reports and analyses by Linda Borg; Scott MacKay; Providence Councilmember Sam Zurier; and the ACLU, the Providence Student Union and Senator Adam Satchell (here at RI Future) have all emphasized the surprising provision that districts may automatically grant, or batch approve, waivers of the NECAP graduation requirement for students who have been accepted to a “non-open-enrollment” college. (General admission to CCRI, for example, would not qualify.) Senator Satchell summed up the critics’ responses well:

Basically they are saying you need this [test] to show us you are ready for college, unless you are ready for college. It kind of baffles me.

And as Providence School Board President Keith Oliveira said at last night’s meeting, https://twitter.com/pvdstudentunion/status/422899860174819328.

Yet while I agree that the college exemption is a theoretical head-scratcher, for the lives of students the college provision is in all a good one, as high-stakes testing opponents have long argued that no one who is accepted to a college should be prevented from attending because of a such a test. However, if this is a “victory”, it is a very small one, for two reasons. First, it is in my mind ridiculous that general enrollment colleges like CCRI are not included in the batch waiver—shouldn’t the state support students who demonstrate their determination to receive higher education? Second, and more importantly, Providence Councilmember Zurier and others have expressed concerns that this specific batch waiver provision does little for the underprivileged, ELL students, and students with special education needs. Likewise, Nina Pande, another Providence School Board member said, “[I suspect] this batch waiver process was really designed for the suburbs and the more affluent districts.” For the approximately 1000 students in Providence who did not meet the cut score in the first go-around, one frankly suspects the college provision will have little relevance.

Quietly undoing the testing requirement

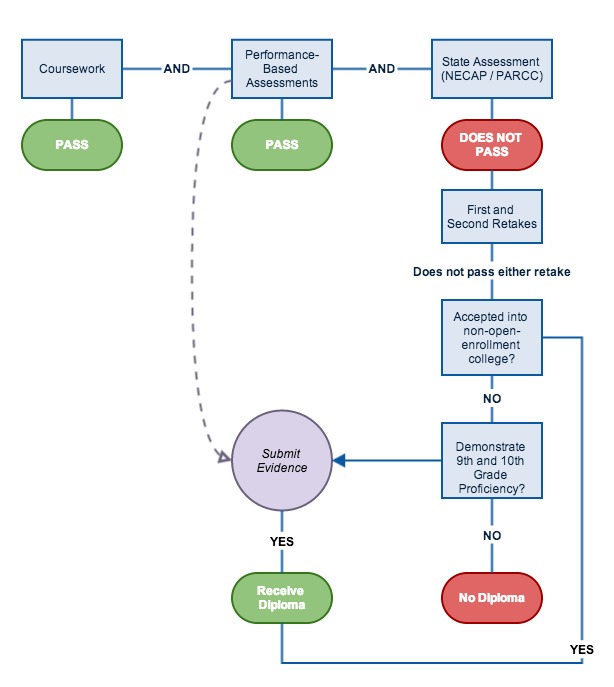

However, a different piece of the new waiver policy still has the potential to allow hundreds of students in Providence in the state to waive the state assessment and receive a diploma. The power lies in each district’s ability to create a “waiver review team” to individually review each application from students who have not met the bar on their first or second test retakes. RIDE has diagrammed and explained the process themselves, but I’ve captured the essence in my own flowchart to the right (click to enlarge).

However, a different piece of the new waiver policy still has the potential to allow hundreds of students in Providence in the state to waive the state assessment and receive a diploma. The power lies in each district’s ability to create a “waiver review team” to individually review each application from students who have not met the bar on their first or second test retakes. RIDE has diagrammed and explained the process themselves, but I’ve captured the essence in my own flowchart to the right (click to enlarge).

Simply put, students who a) have taken both exam retakes, and b) are able to satisfactorily demonstrate 9th and 10th grade proficiency will receive a waiver. Evidence for the latter (cf. page 5) includes “course performance in academic content,” “portfolio work,” and “outside activities/projects”. What’s stunning about this is that students are already to have submitted performance-based evidence in the second of their three topline graduation requirements. A portfolio of strong work, or a researched and well-written project with presentation—both already suffice to show, at the most initial stage, that a student merits a diploma. Now however, the waiver process allows for districts to review performance assessments again to determine diploma status. And as far as I can tell, there are so many accepted means to demonstrate 9th and 10th grade proficiency that the waiver’s standard is actually weaker than the top-line graduation requirement.

In RIDE’s mind, adopting high-stakes testing as part of the graduation requirements had meant setting a hard, quantifiable line that would force increased college readiness statewide. Yet to now allow a qualitative process to supersede a quantitative requirement would seem to obviate the stated purpose of high-stakes testing entirely.

Stress on districts

Implementing a process run by human beings and not test scanners means that school districts statewide must commit serious amounts of resources (read: money and time) to building the new escape hatch. Check out this quote from the RIDE waiver process regulations:

Under our regulations, LEAs [school districts] are responsible for developing and implementing a waiver process. As part of this responsibility, LEAs must:

- Adopt, publish, and communicate a waiver protocol, as part of their graduation policy;

- Establish roles and responsibilities; and

- Evaluate the fairness and consistency with which they apply the waiver protocol to all eligible students.

That’s quite a bit of work to do. And yet, because of RIDE’s make-it-up-as-we-go graduation policies, the Providence Public School District did not approve its own version of the waiver policy within RIDE parameters until yesterday, January 12. Providence now only has a few months to create an entirely new bureaucratic structure. It’s not surprising then that PPSD largely admits that it has neither the staff nor the financial flexibility to implement the waiver policy to full integrity, cf. Superintendent Sue Lusi:

https://twitter.com/pvdstudentunion/status/422900854258417665

And a third Providence School Board member, Nick Hemond, called the waiver process “nonsensical bureaucracy, a burden on administrators…and a waste of time and resources.” It’s no wonder then that some cities and towns have chosen not to adopt the full waiver process, avoiding considerable financial and administrative headaches, but creating vast and inequitable inconsistencies in graduation requirements across the state. Providence, facing the possibility of at most 65% of its students not graduating, hardly had the option to decline RIDE’s offer.

So what have we accomplished?

Challenges of implementation aside, one has return to the above flowchart and wonder what exactly the high-stakes testing requirement achieves, now that its graduation-inhibiting power has been almost fully gutted. The Rhode Island graduation requirements for the approximately 12,000 seniors statewide per year retain little to none of the enforcement power of high-stakes testing post-waiver, but they still maintain the façade of high-stakes, and the exorbitant financial and psychological pressures on districts to implement the waiver process will ensure that all of the most negative effects of standardized testing continue. The most rational (if incorrect) part of RIDE’s adoption of the graduation requirements—raising standards for graduation—is gone, while all of the negative externalities—widespread text anxiety, teaching to the test and curriculum narrowing, unfunded de facto mandates on districts—remain. In the chess game of Rhode Island education politics, Commissioner Gist and the Board of Education just forced a stalemate, to the ultimate detriment of our students.

…or perhaps the graduation requirement has finally achieved its exact purpose. As I guessed from the beginning, the graduation requirement was never about raising student achievement; rather, it was a tool to force districts to dramatically raise students’ seriousness about taking standardized tests, primarily to improve the statewide data set in advance of the expensive PARCC test’s adoption. The increased ‘validity’ of the data then opens the door to value-added teacher evaluation and all sorts of other “reforms”. That RIDE has essentially removed all content from the testing graduation requirement seems to support this hypothesis: it’s not about how high a hoop you can jump through, just about whether or not you take those hoops really seriously. And so the statewide education circus continues.