Hopeful discussion of a possible parking tax earlier this week gave way to the realization that Jorge Elorza and Providence City Council are more likely to forego such a measure, and instead lower the car tax. Sigh. . .

I know that many in the progressive community feel the car tax is too high, or that there should be a higher exemption at the lower end of the price spectrum. I strenuously disagree.

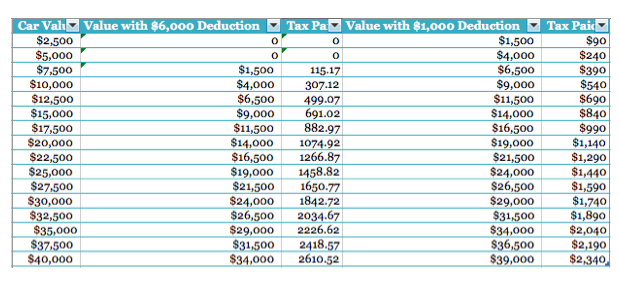

This year was my highest earning year– it was the first time as a child or an adult that I wasn’t eligible for the Earned Income Tax Credit. I made a whopping $17,000 and change, which was matched by a somewhat lower return for my partner. In order to sell products at farmers’ markets, Rachel has recently purchased a car– another first for us. So raising the exemption on the car tax benefits us both as people at the marginal end of the income spectrum and now (gasp) as car owners. But just because something benefits us does not mean that it’s right.

There are many costs to life, and I do not begrudge people for the fact that they dislike paying the car tax. I don’t like paying for things that are expensive either. When we discussed owning a car, we were in full awareness that we’d have to pay a very high car tax, and we agreed as a couple that we would register the car in the city and pay that tax, instead of doing what some people do, which is to find a relative and cheat the system by registering it elsewhere. We agreed that if it came a time that we couldn’t afford to pay that tax any more, that was a sign that maybe we shouldn’t own a car. It doesn’t mean that we love paying a huge sum of money for the car tax. It means we’re mature people who recognize that not paying that tax doesn’t make the costs of car ownership go away. Shifting the costs away from us just means that someone else will pay through a loss of an important program somewhere else in the city budget.

I’d love to see the city target more money to lower income people. I grew up in a marginal income single family house, and at thirty, I still struggle economically. There are people even further down the ladder than I am, and some of them have additional burdens I don’t face. We should of course find creative ways to make our tax system less burdensome to people of low incomes. But why is the car tax always people’s chosen medium to accomplish this?

Why not lower property taxes– especially on multifamily housing and apartments, which are currently taxed at a higher rate (property tax rates go down under the proposed budget, but the Projo notes that the actual amount paid will go up due to higher assessments of properties in the city)? Why not get rid of multiple examples of exclusionary zoning, such as the zoning that was added to Ward 1 to make it less friendly to multifamily housing, and the zoning that excludes more than three students living in five and seven bedroom houses? Getting rid of exclusionary zoning would allow more affordable housing development, which would also bring in more taxes for the city.

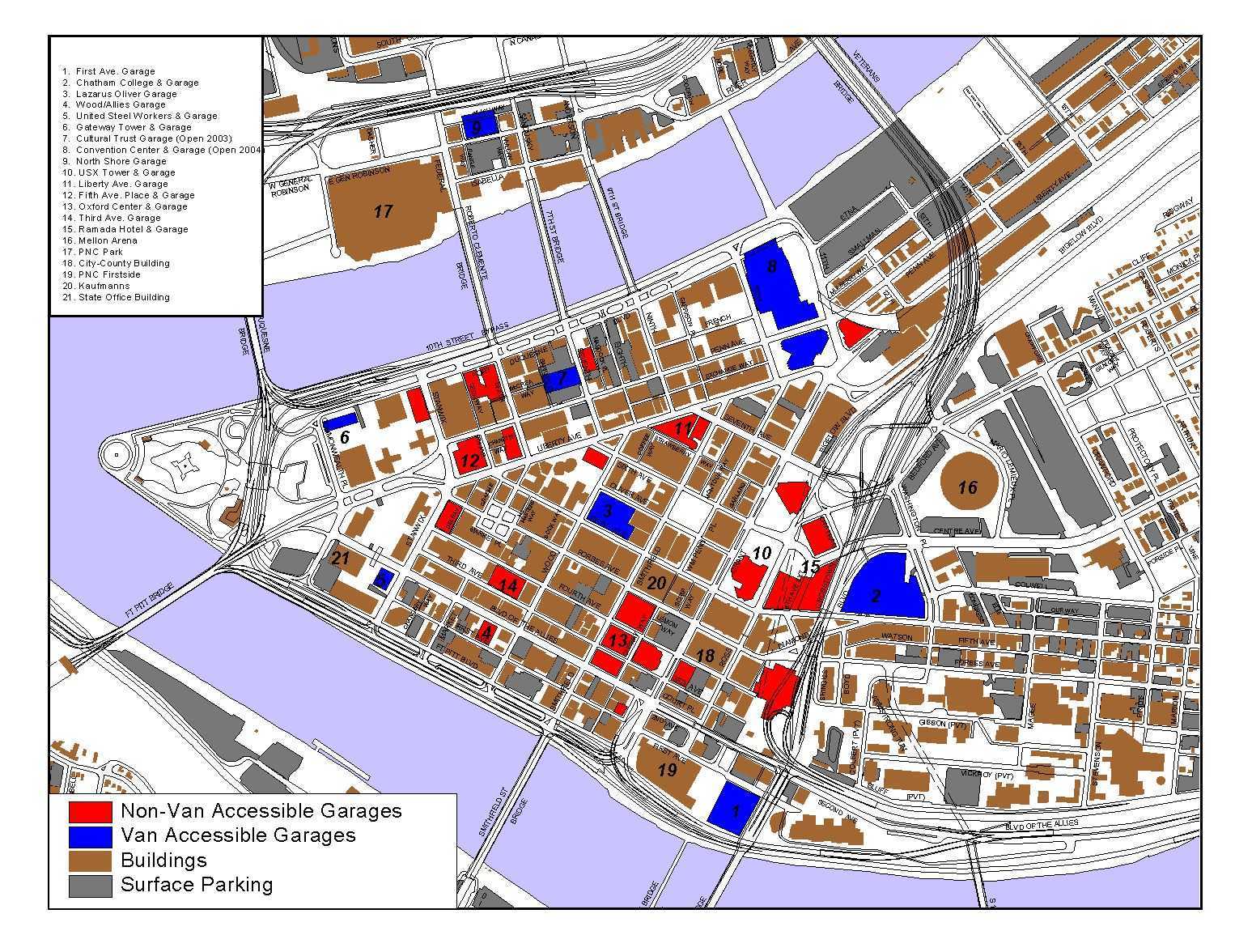

Why not charge a surface parking tax, and use the money to lower taxes on the lowest rung of housing? We know that the particularities of parking mean that the wealthy owners of parking lots and garages– land speculators who aren’t contributing to the city– have to swallow the cost of a new parking tax. That money could be used to help lower taxes on things we want in our city, like housing or jobs. It could also be used to pay for things we like– better schools or transit.

Why not even lower commercial taxes on businesses below a certain threshold? The city has very high commercial taxes, and that means that we often have vacancies. Having a land tax to bring in revenue from big boxes might allow the city to lower costs on smaller businesses, and maybe even fill some vacant storefronts. Those vacancies are part of what makes it so necessary to own a car in the first place– there are fewer jobs and fewer shopping possibilities within distance of one’s house. What more grotesque example of the primacy of driving in our city could exist than Providence Place Mall turning the JC Penney’s across from the train station into additional parking. What exactly are people parking for, as this city of ours hollows out and loses things to visit day by day?

If the city has money to lower the car tax in the midst of a fiscal crisis, then why does it not have money for other social needs? Why can’t we start paying for better early childhood education? Why can’t we figure out a guaranteed minimum income supplement for local residents? Or add the the stipend low income people get for food stamps? Philadelphia recently worked with the private William Penn Foundation to subsidize bike share for low income residents. Providence is still trying to work out a start for its bike share. It costs $5 monthly for any food stamps recipient in Philadelphia to use unlimited bike share in the city. Every time I pay a full dollar to transfer to another bus for the last leg of a journey, I wish I could flash my food stamps card and get that deal.

The truth is that the reason we don’t put more money to schools, or to food security or public transportation or any other need is that if we called for spending on those things, we’d be laughed out of the room. There’s no money! What are you thinking?! But, of course, we have money to cut the car tax.

At the end of the day, we call this “Elorza’s” proposal, and I do not claim to know the internal politics. Lots of people don’t like the parking tax, all across the city, and all across the political spectrum. And why would they? It sucks to pay for things. Maybe the mayor faces pressure from city councilors, or this is part of a deal for something else. It’s still not a good idea. How can we be raising taxes on housing at exactly the time we’re lowering taxes on driving? But when our city has to put bonds out to do basic repaving work, as in the Taveras admin., that’s a sign that we’re running in the red. Why not let car owners pay the costs of roads, so that we don’t let those costs creep into the things we really want to share as a commons, such as our crumbling schools? People should contact their city council people and say that this is an unacceptable position.

No lower car tax. Not when we face such climate problems on our horizon. Not when there are so many other needs.

~~~~