On first reading, I give Economic Intersections, the Make it Happen Rhode Island report from the RI Foundation and Commerce RI a B.

On first reading, I give Economic Intersections, the Make it Happen Rhode Island report from the RI Foundation and Commerce RI a B.

It’s mostly things we’ve heard before like tech transfer, support for manufacturing and regulatory reform. It has some very good, new areas of focus, and it has an interesting idea that doesn’t quite make the grade. But I’m writing this short piece because there is one, glaring, horrifying and totally irresponsible part that defies any kind of logic whatsoever, at least as it is presented in this executive summary.

Good

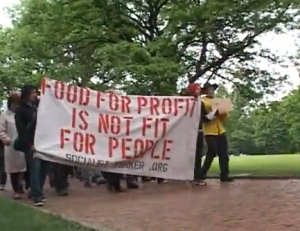

The best part of this is the new focus on food production. There is a clear understanding that this burgeoning sector represents an important part of our next economy, and the report recognizes many important factors in building out the industry. Farms and farmland now have much better visibility within the state’s economic apparatus.

Even better, there is a section focused on the “food-health nexus.” Simply having those two words together in a state-level economics report represents a giant step forward. Medical technologies, neuroscience and bioscience all still hold their places at the top of the economy the report envisions, but actual health and what makes it possible—good, fresh food—is in the mix. Yay!

Not So Good

The report devotes a section to making Rhode Island “stronger and more resilient.” In this area, there doesn’t seem to be a lot of expertise at the table, as evidenced by the goal of creating “scalable approaches to economic development through resiliency.”

Resilience doesn’t scale. Lack-of-scale is the essence of resilience. As I’ve written here many times, resilience is based on redundancy, which is inherently inefficient and therefore not scalable. Many small things within redundant networks so that when some of them experience catastrophic failures—as will certainly happen with greater frequency—the system continues to function through alternate paths. The only thing that scales is the network.

The intention is to spawn companies that develop approaches and technologies around community resilience, as if resiliency were a product. I think what they really mean is “protection from catastrophe,” which is different from resilience. And, certainly, there’s a market to be made in protection from catastrophe, because there will be no shortage of global warming-driven catastrophes.

Some might hold out hope that once the economic apparatus starts to examine resilience and systems-oriented approaches to the impacts of climate change, they may actually/accidentally start to pursue genuine resilience.

But don’t hold your breath. Here’s why.

Blind, Stupid, Irresponsible

I like the top-line idea here: promote access to water and marine-based businesses. When you’re the Ocean State, it’s kind of a no-brainer. But this section of the report has a glaring blind spot, a miss so incredibly stupid that it might be more irresponsible than the 38 Studios deal.

Nowhere in this section—even in this section of the full report—does one find the terms “climate change,” “global warming” or “rising sea levels.” It’s true that they throw a bone to the Coastal Resource Management Council’s current role in this area, but CRMC is conspicuously absent from the list of public entities in the plan moving forward.

The plan is heavy on access to the water and marketing. Which means, of course, building right at the water’s edge. Think “marina access to a mini-resort”.

This represents an irresponsibly short-sighted approach. Coastal properties already have almost no choice but the federal insurance pool, and these costs will certainly only go higher. It is only a matter of time before any coastal infrastructure gets destroyed.

To add insult to injury, the full report refers to New York City’s 2011 Comprehensive Waterfront Plan, and the last of its eight goals is “Increase Climate Resilience.” I mean…right?

This is the kind of pull-your-hair-out stupid that still permeates our econo-think. It’s possible that they never put two and two together to make four. Or it’s possible that “certain powers” deliberately excluded the TOTALLY FRICKIN’ OBVIOUS, SIMPLE LIKE FALLING DOWN CONNECTION HERE!

(As background, Gov. Carcieri’s administration actively worked to suppress any mention of solar power in the RIEDC’s 2009/2010 Green Economy Roadmap authored by yours truly. So this kind of move is nothing new.)

CONNECT. THE. DOTS!

I know this is complicated, so I’ll go step by step.

1. The report is called Economic Intersections, so it’s about connecting things that might be complementary.

2. One idea in the report is to develop marine-based businesses, following New York’s waterfront plan.

3. New York’s waterfront plan includes increasing the waterfront’s resilience.

4. Another idea in the report is to develop resilience.

It seems so elementary, so obvious that I’m embarrassed to have to spell it out like this, but…here goes:

Focus your resiliency efforts on the coastal impacts of global warming-driven sea level rise and catastrophic weather events so that your marine-based businesses can be, oh, I don’t know…resilient.