The arguments against the death penalty are clear and compelling, and I am not going to restate them here. Instead, I am going to attempt to show that the death penalty phase process, that is, the way in which we determine whether or not someone like Dzhokhar Tsarnaev is to be put to death, weaponizes the grief of victims and families of violent crime and ultimately dehumanizes all of us.

Tsarnaev committed monstrous acts of indiscriminate murder and terrorism. There is no excuse or justification for his crimes.

The way we determine whether or not the death penalty is to be applied is that a trial is separated into two phases. The trial phase, in which guilt or innocence is determined, and the death penalty phase, in which the jury considers whether or not the crimes are worthy of death.

Juries for death penalty cases are made up entirely of people who are pro-death penalty, at least in theory. In essence, every member of the jury disagrees with my assertion at the beginning of this piece, that “the arguments against the death penalty are clear and compelling.” Believing that the death penalty is wrong disqualifies a person from being on such a jury. Anyone with a religious or philosophical objections to the death penalty, and this would include many of the great moral leaders throughout history, are excluded from the process.

This is important because, when looking at the facts of the case, no one is more deserving of the death penalty, under the law, than Dzhokhar Tsarnaev. If the death penalty cannot be applied in the case of the Boston Marathon bomber, it applies to no one. Therefore, a jury of people who think that the death penalty is at least sometimes justified, is all but sure to apply it in the case of Tsarnaev. The jury becomes a loaded gun, and the prosecution merely needs to call the witnesses required to help pull the trigger.

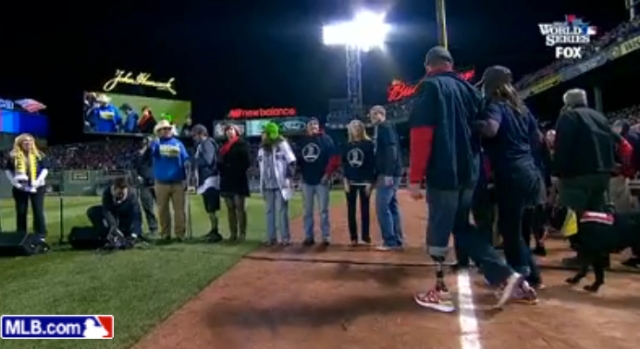

During the Tsarnaev death penalty phase, the prosecution called family members of those who lost their lives. (For a complete picture of the process, see this excellent Washington Times piece.)

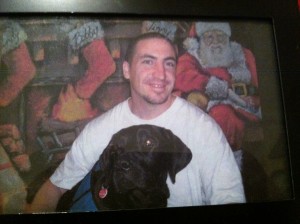

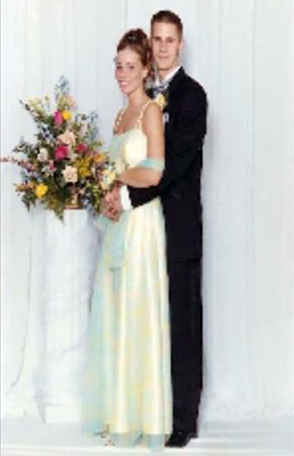

William Campbell Jr., the father of victim Krystle Campbell who was killed in front of Marathon Sports, was called to the stand Tuesday afternoon. The jury was shown pictures from Krystle’s entire life, including her prom picture.

‘I miss my hug everyday. She never left the house without giving me a hug.’

Jurors, says reports, “were brought to tears.”

As much as I am personally against the death penalty, I know in my heart that if my daughter was killed or grievously injured, I would be in court testifying for the execution of the person responsible, just like Campbell. I know that I would want my testimony to have the maximum impact. I would want the jury to understand that my daughter means as much to me as their loved ones mean to them. I would want them to imagine that my daughter was their daughter, and act on that emotion to punish the person responsible.

I could see myself throwing away everything I believe to satiate my need for vengeance and closure.

But in a world where there is no death penalty, my closure would not rely on the possibility of an execution. My closure and my healing would begin when Tsarnaev is locked away forever to dwell upon his crimes, never again to harm another person.

The death penalty phase asks victims and families of victims to use their grief, their loss and their misery as weapons. The only thing we truly have of those we lose is our memories, and this process requires that we use those memories not for joy and solace, but to punish and kill.

I cannot condemn those who choose to participate in the process and testify for the prosecution in the death penalty phase.

I would do no less.

But I do condemn a system that appeals to the worst in our natures, and encourages us to use all that we have left of our loved ones as an instrument of state sanctioned murder. Such a process is dehumanizing and worse: it forever darkens the legacy of those we have lost.