Currently, for a party to be recognized by the state, they must collect signatures totaling 5% or more of either the Presidential vote or the Gubernatorial vote (whichever was more recent). Then, in the next election, to maintain their party status, they have to win 5% of the vote in that category, and then every four years win 5% again.

That threshold is designed to keep third parties from being recognized. Plurality, winner-takes-all voting schemes like Rhode Island’s practically force voters to vote strategically and over time reduce the amount of parties down to two. Lowering the threshold to a more manageable number like 2% of the vote would be a start. Alternatively, the requirement could be 5% of the Gubernatorial vote and then a requirement to win 5% in any statewide race. Another would be to keep the signature requirement and an interval after a reasonable period of time to force that collection again (however, this would mean that Republicans and Democrats were forced to do this as well). Finally, dropping the signature requirement altogether and making sure that parties met a set number of requirements could also open up our party system.

Instant Runoff Voting (IRV)

I’ve mentioned this before, and the General Assembly passed the Voter Choice Act in 2011 to study IRV. The study commission was due to report on May 1, 2013; but a House bill by Rep. Blazejewski (a member of the commission) was passed on July 3rd to move the date to November 1st. Don’t ask me how that works.

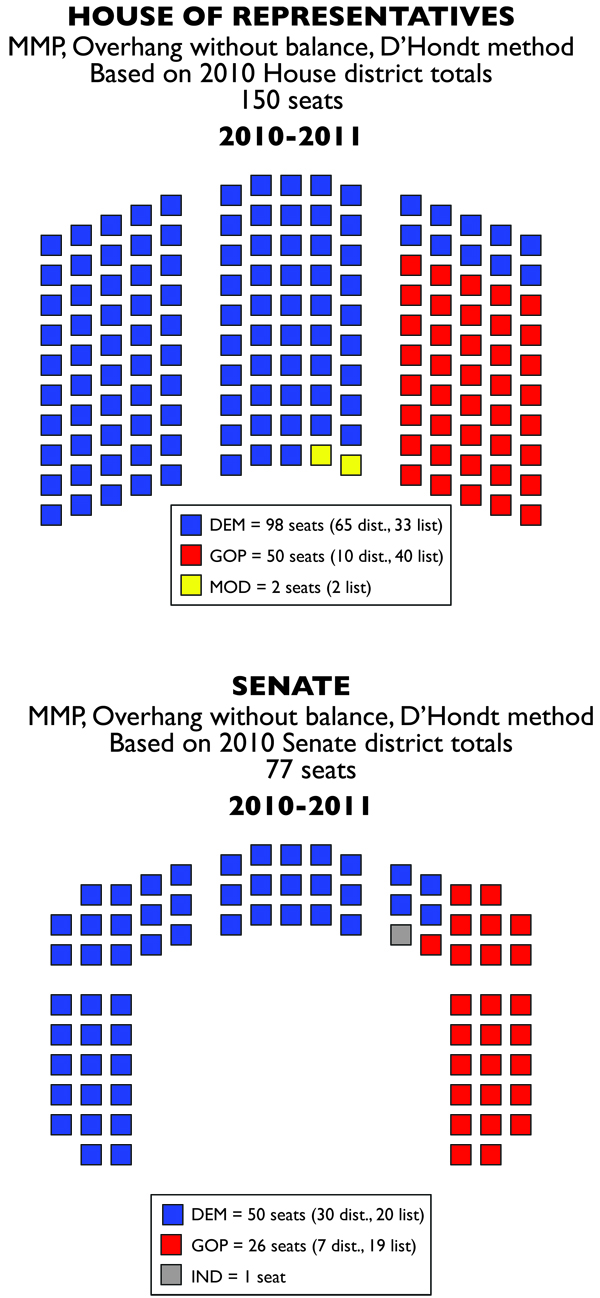

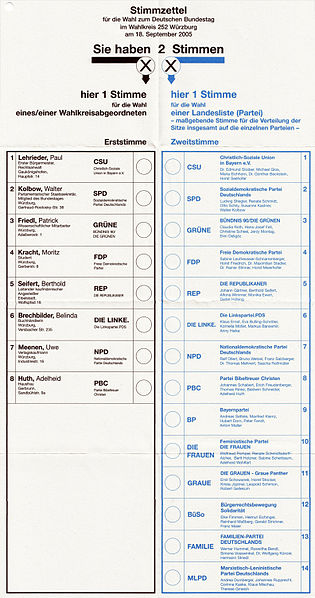

IRV allows voters to rank their choice of candidates, preventing the spoiler effect that third party candidates and independents can have (as a result, IRV systems foster multiple parties). In an MMP system, it could greatly change how district seats are awarded. In Rhode Island, this could ultimately mean the end of Democratic dominance in the districts.

Revamp Election Day

Election Day sucks. A working Tuesday is a terrible day to hold an election. Miss it because you were sick or had work, and you have to wait two years (and no guarantee it’ll be the same election then. Beyond early voting and extended voting times, one of my favorite suggestions was to turn Election Day into a week-long paid-holiday/celebration, complete with things like parades and fireworks. Considering it’s the part of our democracy that’s the most democratic, I think that’s a good idea.

Stop/Reduce Gerrymandering

Gerrymandering can create a way for a party to cling to power even when it should’ve been defeated. This problem is endemic across the United States, but it’s only receives attention in the run-up to redistricting, during redistricting, and in the immediate aftermath. While MMP ostensibly works to counteract gerrymandering, how districts are drawn is a better solution, since it works across electoral systems.

Bipartisan commissions bother me, since incumbents always have a reason to draw themselves safe districts. Independent commissions also bother me, since legislators are pretty good at finding a way to work around nominal independence. I don’t have a very good solution, but the shortest-splitline algorithm seems like a promising way to counteract it; though it leads to districts that often ignore geographical features and boundaries. I’ll let this YouTube video explain it:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kUS9uvYyn3A

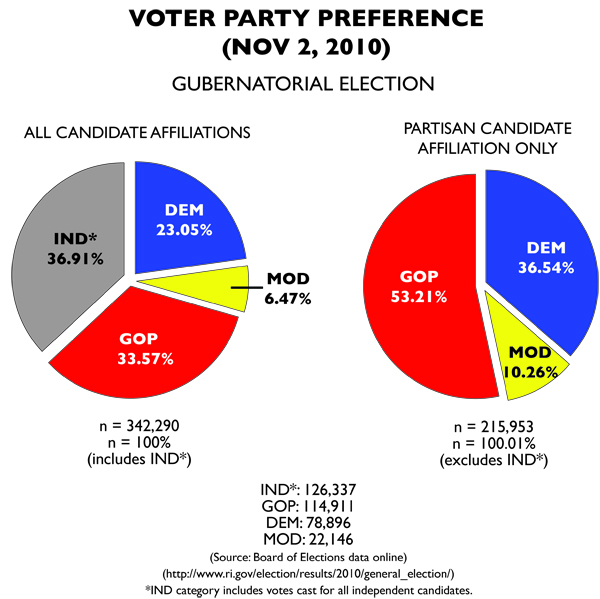

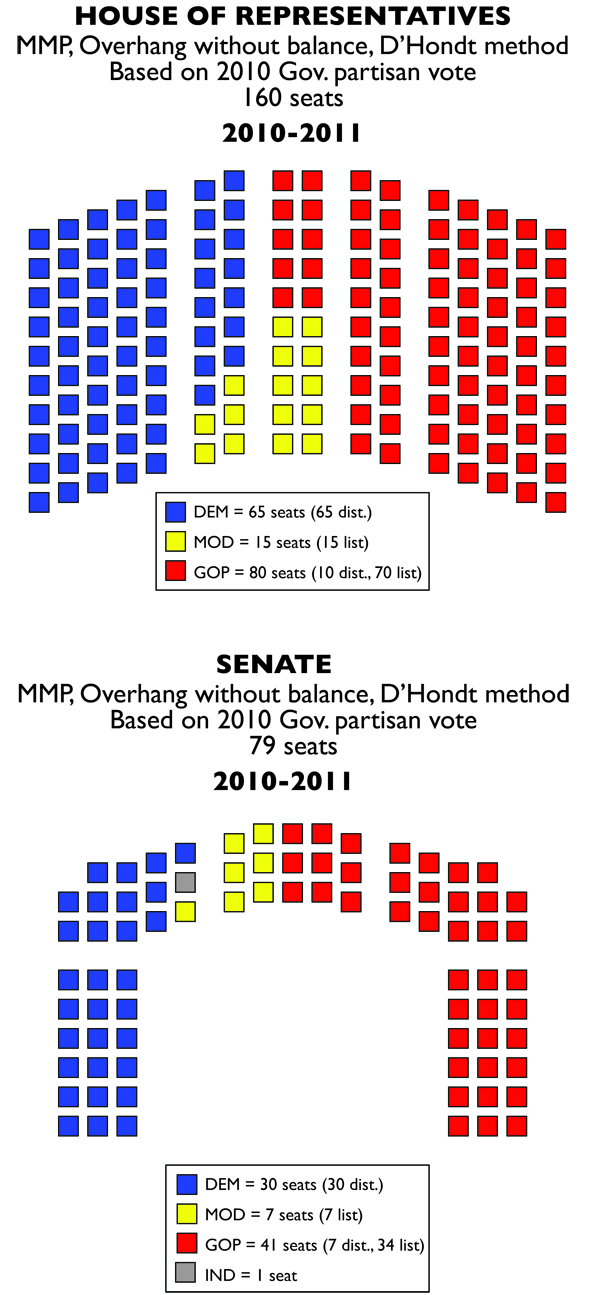

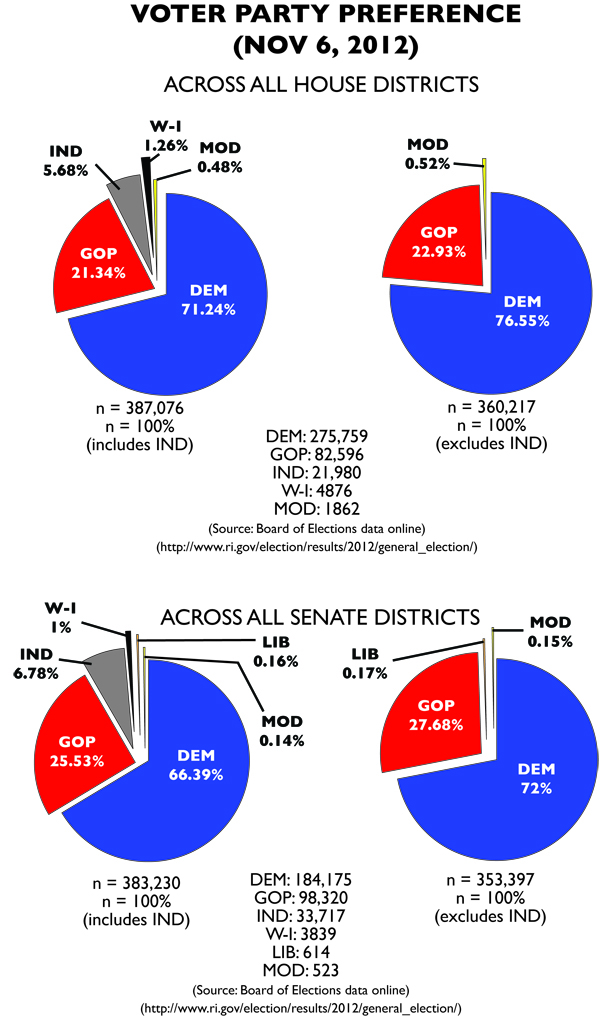

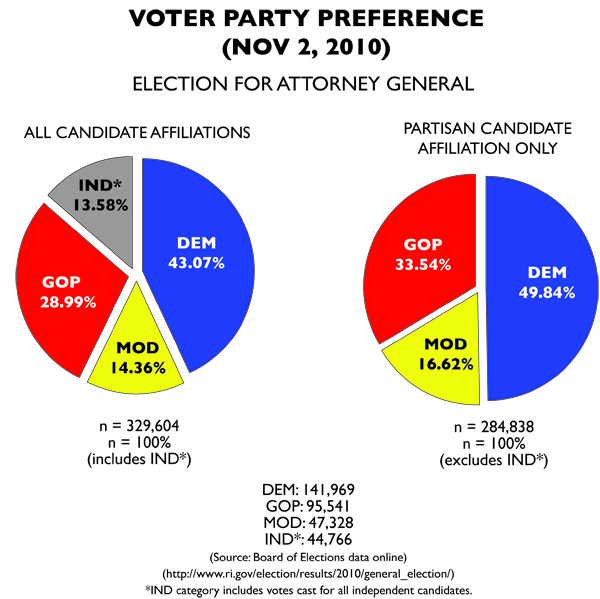

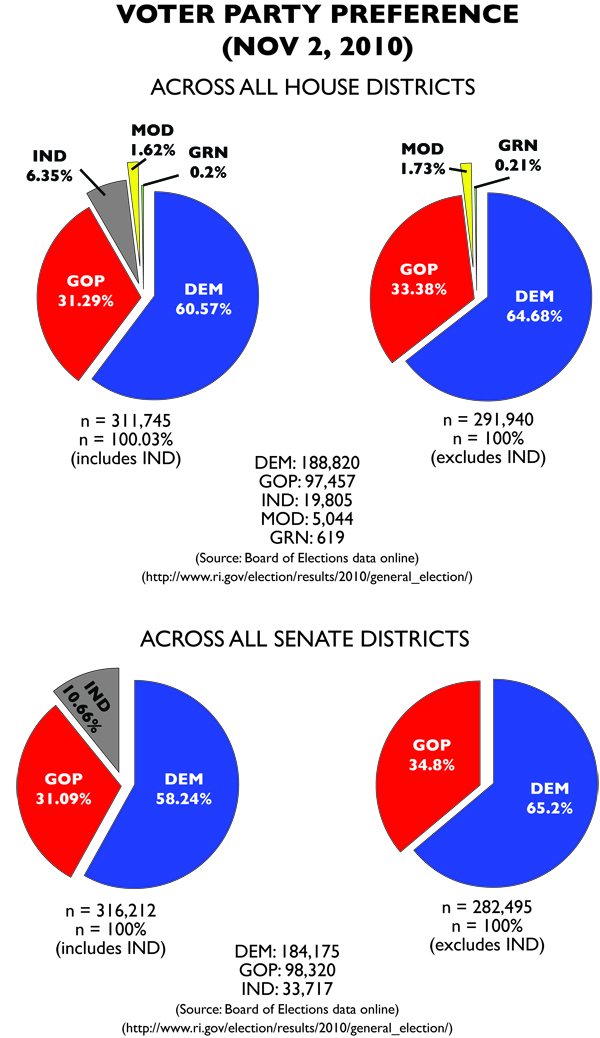

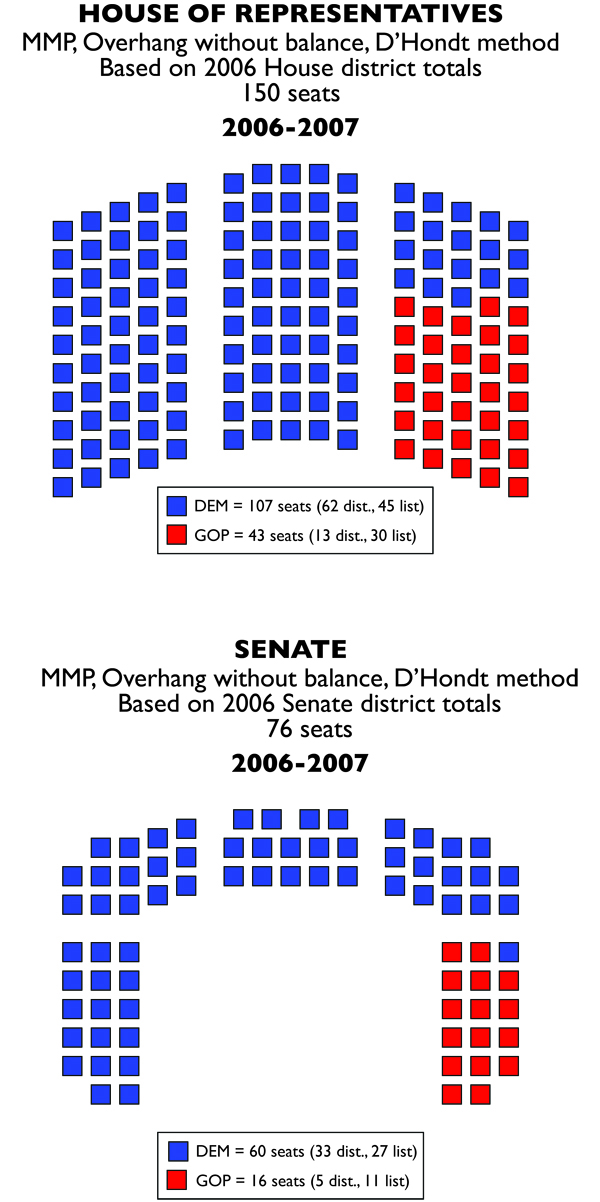

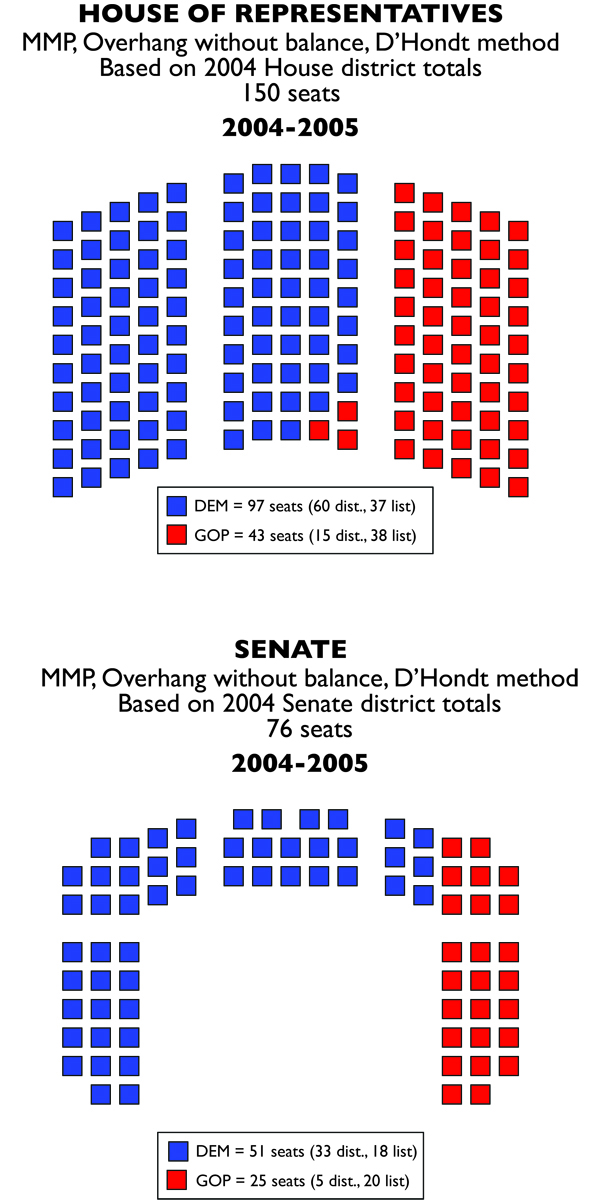

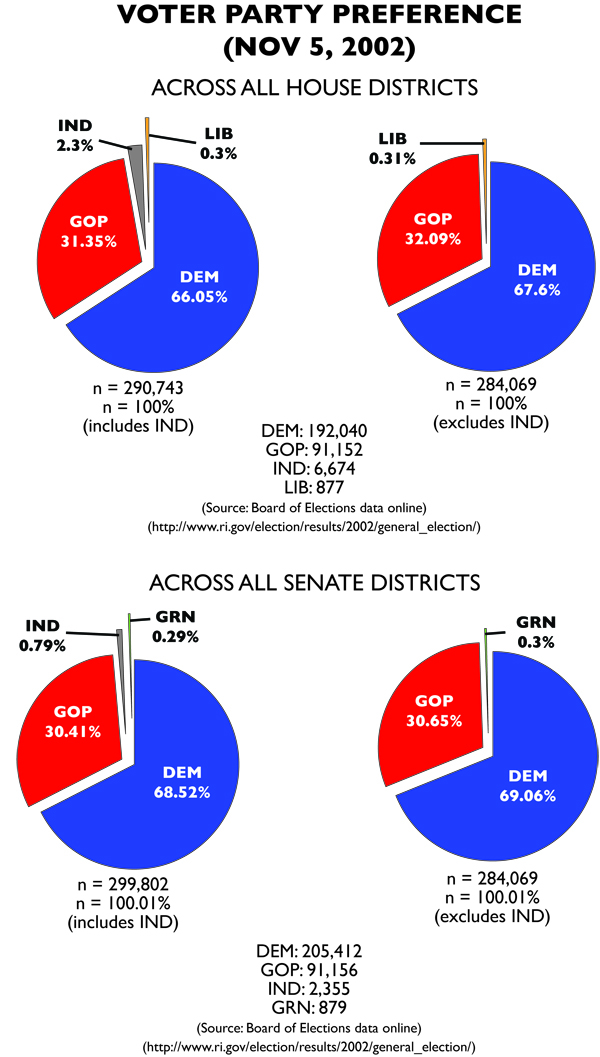

This is Part 13 of the MMP RI series, which posits what Rhode Island’s political landscape would look like if we had switched to a mixed-member proportional representation (MMP) system in 2002. Part 12 (a revisiting of the 2010 election based on Attorney General election results) is available here. Part 14 ends this series.