In the introductory post of this series on housing in the Providence metro, I laid out some basic concepts in antithetical pairs. I sought to show how policy advocates and community activists argue their competing viewpoints within a zero-sum logic, usually to the detriment of both. This post examines the process of radical neighborhood change commonly called gentrification. Like so much in life, it’s a good thing right up until it goes horribly wrong.

I gentrify

I sometimes describe myself—tongue in cheek—as a ‘serial gentrifier.’ For nearly 3o years, I have spent some amount of my time renovating buildings in San Francisco, Burlington, VT and greater Providence.

I have moved from city to city and neighborhood to neighborhood, always in the first wave of change in communities that would later be described as ‘gentrified.’ By they were considered gentrified, I was long gone, tearing out crumbling plaster in a neighborhood where few people would choose to live.

I have seen this process occur repeatedly, and I understand the basic mechanics. I also know that gentrification is not necessarily the inevitable result of a change to a more affluent demographic. Given certain rare conditions, this process can improve quality of life for most existing residents.

I have seen this happen in exactly one place: Mt. Hope in Providence. This neighborhood is largely gentrification-proof, and community-oriented urbanists would do well to study why.

How gentrification starts

For a neighborhood to become gentrified, two types of properties must be present is significant quantities: vacant properties and absentee-landlord properties. Those in the know may already predict that owner-occupation, regardless of socio-economic conditions, is the key factor that prevents gentrification.

Here’s how it works. Some young person—probably white, probably non-traditional, probably an artist, probably leftwing, probably already connected to low-income and/or minority communities—decides to get out of the losing game of paying rent on some crappy apartment. The one thing we know for certain about this person is that he or she is skilled in multiple construction trades, probably from some years working in the industry. If he or she is not, that’s about to change real fast.

This person has scraped together some pittance of a down payment, but can’t qualify for a mortgage, so he or she scours the very bottom of the real estate market—burn-outs, abandonments, tax foreclosures, bank-owned properties. Perhaps someone they know tips them off to a building on their block that can be bought for next to or for actually nothing. This building is probably legally uninhabitable, but this doesn’t stop our young person. In they move, and the rehabilitation begins.

This person’s friends start coming over to their house, and pretty soon one of those friends—slightly less non-traditional, slightly less leftwing, slightly-less connected to the community—buys a slightly less bombed-out piece of crap.

As this process continues, several things are happening. First, the number of abandoned properties starts to decline. Second, the condition of the worst property starts to improve. Third, the demographics of the buyer trend ever wealthier and more conservative. Lastly and most importantly, the price paid for the building starts to increase.

Conditions for local residents

To this point, local residents generally see these changes as positive. More people and fewer vacant houses generally improves safety and quality of life. Streets start looking nicer and on rare occasion an absentee landlord decides to put a little effort into improving a rental property. “Finally,” locals often remark, “it looks like somebody cares about this place.”

The only time I’ve seen this go otherwise was in a neighborhood in San Francisco now called Hayes Valley. The aftereffects of the 1989 earthquake played an enormous role in this neighborhood, but in 1985 it was largely African-American, largely supported by public assistance and largely bombed out. Drug-addicted prostitutes plied their trade in the area under the elevated highway. Such was my neighborhood.

My first rehab was the apartment where I lived, in exchange for rent. Like four of the six units in the building, it had been a flop for junkies. (Crack cocaine was about a year away from exploding into the urban environment.) I had grown up in the suburbs of New York and never lived in the inner city. It was a learning experience in many, many ways.

The problem for local residents in this slowly changing neighborhood was not that new residents were white or that they were more wealthy. The problem is that many of them were gay men. AIDS that year was epidemic in San Francisco, and less informed people of all walks of life feared any gay man. But even without AIDS, some portion of this neighborhood expressed outright homophobia, sometimes in very ugly ways. “I’m moving to my cousin’s in Oakland,” was a common theme amongst this set.

Even though his grown son had left for Oakland, my 70+ year old upstairs neighbor wouldn’t. “I don’t care if they [redacted],” he once said of the next door building’s owners, passing me a joint. “Place looks nice.” (A WWII vet and retired civil servant, his apartment was barracks-neat. He painted it himself on a continuous basis, as he had ships in the US Navy. Fabulous human, he was.)

Where it all goes wrong

So far, our hypothetical neighborhood has seen its abandoned properties get renovated and its demographics trend wealthier and whiter, but without negative impacts on the existing residents. That’s about to change. And once this part of the process begins, it won’t end until the neighborhood is completely transformed and virtually all of the original residents are displaced.

At some point, there are no more abandonments left, no more burnouts. Around the same time, the demographic mix reaches a tipping point where very white, very traditional, relatively wealthy and relatively conservative people see the neighborhood as a desirable place to live. Young couples clear the way for families with young children, and this is commonly the point at which true gentrification occurs.

Realtors likely did not participate in the first few sales. These tend to be owner-financed or bank purchases (REO/OREO) or facilitated by a government or non-profit. But eventually realtors become participants. Perhaps a young, ambitious realtor buys an abandonment and pays a crew for the rehab. (This is another data point indicating that bad things are about to happen—owners stop doing the work themselves and instead pay professional crews.)

Many realtor are also property investors, aka, absentee landlords. So before too long, absentee landlords recognize that selling their buildings could yield substantial cash profits. So realtors connect our mid-wave buyers (let’s call them) with absentee landlords, and the real problems start.

Most places have very weak tenants rights laws, and a change of ownership generally voids the lease. But most long-term tenants don’t have a lease because landlord-centric laws default expired leases to “month-to-month” agreements, meaning that either party can terminate the contract with 30-days notice. Lobbyists typically sell these laws as empowering tenants to get away from bad landlords, but the opposite is closer to the truth.

Eviction and homelessness

Gentrification’s endgame plays out with a distinctly ugly character. Longtime residents who had always paid their rent on time are turned out into the street with eviction notices. Or perhaps the new owner raises rents to force an eviction. (This past month, this occurred to one of the young people I mentor at an afterschool program. He and his family are now homeless, forcing him to drop out of the program and his GED courses. Yay, capitalism!)

It really doesn’t matter which way it happens, and the new owners rarely care one bit about what happens to these people. “They should get better jobs if they want to live somewhere nice,” is a typical sentiment.

We see this dynamic today in places like San Francisco or Harlem and Brooklyn in New York City. This wave has largely swept past the West Side in Providence and is headed toward Olneyville as I write.

Fight gentrification before it happens

The only way to prevent gentrification from occurring is to prevent its prerequisite conditions from occurring. In plain language, community organizations should focus as much energy as possible into transferring abandonments to local residents.

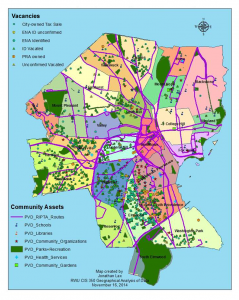

The map at right was put together by local activist and RI Future reader Jonathan Lax. He is also a former title examiner and worked many, many transactions during the housing bubble. He is currently studying a cluster of interrelated issues in the Providence real estate market, including vacancies. This map shows Providence properties in some state of vacancy, foreclosure or abandonment.

Except this: he’s only got about 60% of the data fully parsed and added to the database. 40% of the abandonments in Providence are not in this map. The completed map will be about 2/3 denser. But already it shows pretty clearly the neighborhoods most susceptible to gentrification.

In 1997, I bought my first building; it was in Providence in the grey area between the Mt. Hope and Summit neighborhoods. Despite an influx of upscale whites, this neighborhood remains highly diverse because a very large percentage of the buildings were already owner-occupied. On the block where I bought this three-family, three of the six houses were owned by one extended African-American family. The building I bought was the only absentee landlord building in the four-block area. But then I moved in with my young family, and their were no absentee landlords at all.

People I know on Camp Street tell me that back in the 1970s and 80s, when the neighborhood and the rest of the city were at a low point, the Stop Wasting Abandoned Properties (SWAP) program in that area specifically targeted young, local renters to take over these properties. Today, these no-longer-young owners are passing on their properties to their grown children. Better yet, they are using the equity in their homes to help their children purchase contiguous or nearby properties.

Returning to the map, I hope that the CDCs and other community groups in Olneyville, Elmwood and the lower West Side can act aggressively to get these properties into local hands. [I have no data to support this, but my gut tells me that Silver Lake likely has a higher than average rate of owner-occupiers that survived the bubble. It’s a dense cluster, but I rank it well below Olneyville/Manton, which I think is Providence’s most gentrifiable neighborhood.]

Low-income communities and communities of color rightly fear the encroachment of affluent, white buyers; in almost all cases, it will lead to their eventual displacement. Rather than mount a futile campaign to stop the worst aspects once they start, people should recognize that every abandoned property is an opportunity to keep their community together.

But they have to buy-in to the process. Literally.