As I was writing this article, Senator Sheldon Whitehouse and a number of his colleagues started tag-teaming an all-night marathon of speeches on climate change. The move feels like progress, but also has that “that should have happened 20 years ago” feeling that so many Democratic tactics have in Congress.

As I was writing this article, Senator Sheldon Whitehouse and a number of his colleagues started tag-teaming an all-night marathon of speeches on climate change. The move feels like progress, but also has that “that should have happened 20 years ago” feeling that so many Democratic tactics have in Congress.

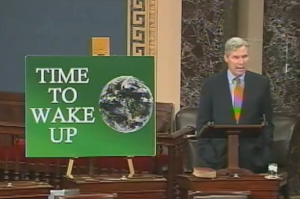

I can’t help but think of the filibuster every time I see one of Sen. Whitehouse’s speeches. While the filibuster of today is mostly a procedural technicality, some senators on the left and the right have taken to doing a real “talking filibuster” like the kind you might expect from a Webster or Calhoun of yore. But it’s time to wake up. Whitehouse needs to reevaluate his strategy on climate change and push more forcefully to stop it.

The filibuster is a powerful tool, having just recently killed a bill with majority support to remove sexual assault cases in the military from the DOD chain of command. The bill, sponsored by Democratic Senator Kirsten Gillibrand (NY) was taken down by friendly fire within the party, as Sen. Claire McCaskill’s (D-MO) sought to keep prosecutorial decisions in the chain of command and proposed more minor changes to the assault process. Situations like this show how effectively the tool of obstruction can derail a good thing, even when it has fifty-five votes.

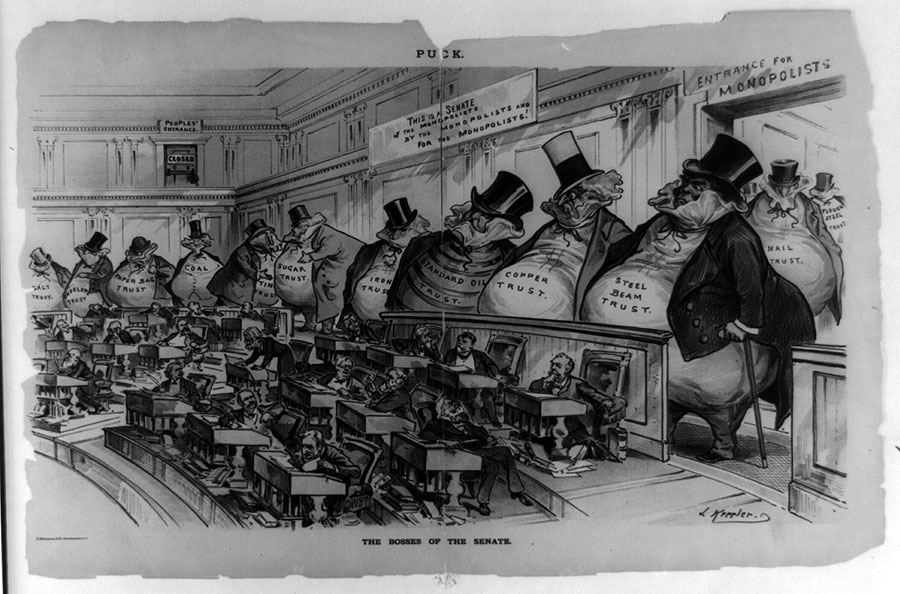

The filibuster has been a primarily rightwing tool in our history, although at times left-leaning senators like Bernie Sanders or the LaFollettes have used it for liberal causes. I think that Senator Whitehouse needs to rethink his strategizing around climate change to include the filibuster as a tool of obstruction for good rather than evil.

I’ve written elsewhere of the relative sanity of our dear senator, Sheldon Whitehouse, as compared to such uninspiring figures of my Pennsylvania upbringing as frothy-mouthed Rick Santorum. Rhode Island is lucky to have a senator like Sheldon Whitehouse, who embodies everything that is relatively sound about our otherwise dysfunctional Senate. I’m certainly surprised everyday to find myself feeling like I can respect someone in the Senate that I have the chance of voting for myself.

Senator Whitehouse has made a weekly speech about climate change on the Senate floor for over a year to the adulation of many liberals. While one usually refers to these speeches as being “to” the Senate, I think the more cynical C-Span junkies among us are aware that there are often very few actual co-members of either house that actually listen to them. Some of the best political speeches I’ve ever seen have included accidental pan-out by the cameraperson at the last moment to reveal just a couple of staffers and one or two congressional colleagues, a cameraman, and a stenographer in the audience.

Like Bernie Sanders (I, VT) and Rand Paul (R, KY), Sen. Whitehouse represents a state in which being pushy about his ideals is a safe bet. Fully 92% of Rhode Islanders believe that climate change is caused by human actions. Certainly in a swing state like Ohio or Pennsylvania, or in a conservative state like Kentucky, giving a speech weekly on the need to address climate change would be ballsy, and no-doubt much of the pride that we get from seeing our dear Senator do this each week comes from the recognition of how far in advance of other states this puts our leaders. But by the same token, in a state where the public is so cognizant of the need for action, is making a weekly speech even touching the surface of what’s enough?

We need to understand laws in terms of power, and not just as some sweet exercise in reaching across the aisle. The historian Robert Caro, who has written biographies both of Robert Moses and Lyndon Johnson, had this to say (video) about Johnson, who he calls “the Master of the Senate”:

You know today, political scientists say that the eleven weeks between Election Day and Inauguration Day is too short a period of time for a president to learn–for a new president to learn–to be president. Well Lyndon Johnson’s preparation, his transition period, was two hours and six minutes. That’s the length of time between when he takes his oath on Air Force One to be President of the United States, the plane takes off immediately thereafter, and two hours and six minutes later it lands in Washington, and he has to be ready to step off that plane, and become president…Kennedy’s entire legislative program–his Civil Rights Act, his education act, his Medicare acts…all his major legislation, without exception–was stalled, completely stalled in Congress. It was going nowhere. . .[A]s you know, since 1937, Franklin Roosevelt, Harry Truman, Kennedy had not succeeded in getting a single piece of major domestic social welfare legislation through Congress. To see Johnson walk directly into a situation where Congress had completely stalled this bill, all these bills, and to see him get them up and running–within one week he has them all on the way, beginning at least, on their way to passage in Washington–to watch him do that is a lesson in what a president can do, if he not only knows all the levers to pull, but has the will, in Lyndon Johnson’s case the savage, almost vicious drive to win, to accomplish, is to say over and over again, ‘Wow, look what he’s doing! I never knew a president could do that!’ [my emphasis]

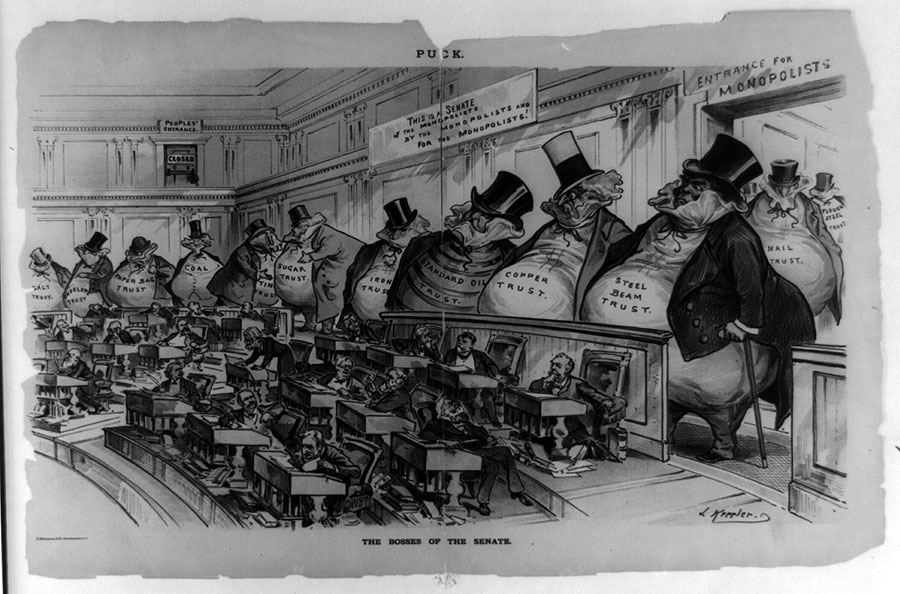

Caro explains in his multiple volumes how the Senate has historically used its filibuster mostly to the detriment of positive social change, between Reconstruction and the 1956 Civil Rights Act blocking each and every attempt to make even the most gradual changes for black people and unions in the United States–with Johnson himself often at the helm of such retrograde senatorial actions. The development of an uncompromising activist movement for change alongside a real son-of-a-bitch that was willing to do what he had to do in government meant reform.

Caro explains in his multiple volumes how the Senate has historically used its filibuster mostly to the detriment of positive social change, between Reconstruction and the 1956 Civil Rights Act blocking each and every attempt to make even the most gradual changes for black people and unions in the United States–with Johnson himself often at the helm of such retrograde senatorial actions. The development of an uncompromising activist movement for change alongside a real son-of-a-bitch that was willing to do what he had to do in government meant reform.

Caro’s book shows that the obstructionism that we see today in the guise of the Tea Party is not a short-term strategy. Obstruction has been a good strategy for the right. As with the Goldwater campaign during the Johnson years, the right often loses in its first attempts to grasp for impossible ideas, but their willingness to go out on a limb with an unpopular view sets them up for victory later–the Reagan Revolution was staged, it’s said, on Goldwater’s shoulders. It doesn’t matter how objectionable the goal, the fact is that a political leader is willing to fight for it makes it part of the conversation, and that creates a new normal. Climate change denial, in fact, has become the ultimate example du jour of this strategy. There’s no rational reason for denial, as Sen. Whitehouse knows, but the media is only gradually waning from presenting both “sides” of the argument–and sadly, in many cases this waning still takes the form of shilling for natural gas companies or other dead end solutions. Whitehouse mistakes the problem. He can give a speech each week until the Potomac becomes brackish and comes lapping up to his knees on the Senate floor, but his colleagues that refuse to act on climate change won’t change their minds because of education. As with every great struggle in political history, this one is one of power. Indeed, it’s time to wake up.

Parliamentarian liberals perhaps don’t obstruct as often as their colleagues of the right because they see themselves as passers of bills. But perhaps we should start to look not just at what we can do about climate change, but also at what we can stop doing. In this regard I think that Whitehouse himiself has far to go.

Bikes and transit

Sen. Whitehouse has been an admirable advocate for funding of bike and transit projects, but hasn’t looked closely at the projects he advocates for that undermine his good work. In 2012, for instance, Whitehouse ingloriously begged (video) for a visit from then Secretary of Transportation Ray LaHood to come see the Mall and the huge highway interchange behind it, known as “the Viaduct.” To my eye, there is no feature of the Providence landscape that more deserves to be torn out than the highway stretch starting at that exchange and continuing through U.S. 6 & 10 to Roger Wms. Park. These highways are a jumbled mess that cut off local streets from one another, make it impossible to bike or walk between neighborhoods, and provide no transit alternatives other than to travel into Kennedy Plaza and wait to go back out on another ineffective bus. Yet to Whitehouse, who I’m sure was sincere, I think the lens was “What can we build?”

Caro, who was a scholar not just of Johnson but of Robert Moses–the architect of many of America’s urban transportation nightmares–said it well. It’s not just what we build that counts. It’s what we don’t build. I clipped (video) from a longer book discussion (video) on C-Span:

We have to remember that exhibits show you physical things, and the mark of Robert Moses is much more than anything you can see physically. In part you have to analyze in priorities, because he got enough power that decade after decade, certainly from 1945 forward, he set the city’s priorities. . . For decades he played a crucial role in determining where the city’s resources would go. In the book, I tried to detail the way he skewed spending away from the social welfare aspects of city government, and towards the physical construction of the city. . . Now, in the last years before the Second World War, let’s say 1939, ’40, ’41, the city was having an influx of people from the rural areas of Puerto Rico and the rural areas of the South, and he city’s elected officials, the officials that supposedly had the power, had an understanding that the city should reach out to them. . . [Mayor] LaGuardia had a unique empathy for people and for what they needed and it was really his idea to have what he called baby clinics, because he understood that people–poor people–were intimidated by hospitals. . . Year after year, the same thing would happen. At the last minute, LaGuardia would have it in the budget. He had promised when he ran for office that he would put money into schools, hospitals, and baby clinics, and year after year Robert Moses would show up, and it would always be with the same argument, that was can get 90% of the funding for this or that–some big highway or bridge project from the federal government–and if I can only get 10% to get it started. The 10% always had to come from somewhere, and it always seemed to come from this kind of program.

It’s interesting to think of the time in which Moses was playing these games, because these were times where, although the federal government had begun to play with the idea of deficit spending, people still thought in terms of priorities. Of course, at the local level, we still have to think that way. Yet as the idea of Keynesian growth has taken off, and as liberals like Sen. Whitehouse have adopted it, that idea has fallen away. Today we act almost as if there’s no connection between massive urban highways and their alternatives, or between the social malaise of our state and the unmet obligations it has–not to food stamps, or pensions, or schools–but to overgrown roads. Caro ends his anecdote with a letter to Moses from a New York City official, which underscored that if the transportation project was built, the baby clinics would not happen. “Where are the baby clinics?” the letter asked. I think we need to toss aside Keynesianism precisely because it fails to sharpen our minds around these questions of spending priorities.

The Highway Trust Fund gets appropriations reauthorized each year. Streetsblog has recently reported that Pres. Obama has put forward a much improved mix of spending for our transportation system, and if that can get passed as is, so be it. But the chances of that happening without hitches are nil. The most important reason that liberals like Sen. Whitehouse need to stop thinking of themselves solely as passers of bills is that it gives their opponents–the obstructors of bills–all the power. Tea Party extremists can challenge non-highway related allocations, like a bill sponsored by Rand Paul attempted to do, and liberals are then left scrambling trying to defend their allocation choices. Instead, why not go to the root of the problem and start chipping away directly at the highway part of the bill–insisting not just for a greater share of funding, but also for reductions in the size of the bill in total? Senators like Sheldon Whitehouse who care to see climate change halted need to see beyond just what they can pass affirmatively, and also see what they can stop. And if doing one of those speeches on the Senate floor–with teeth this time, as a filibuster–means that some bike path or bus improvement in Rhode Island gets delayed, transportation advocates should be willing to give Sheldon Whitehouse a pass if what we get in return is additional highway spending blocked, or another highway removed completely.

What I like most about this idea is that a filibuster of spending realigns the Congressional political landscape in a way that reflects conversations that have been happening at the grassroots for decades. Liberals like Jane Jacobs focused in the urbanist aspect of their activism on what could not be done to cities rather than what could be done and came butting heads directly against the likes of Robert Moses. Taking transportation debates to a place that liberals have been afraid to go–talking about reducing the role of the federal government in a way that would truly reduce the role of highways in our lives–by stopping the unhealthy diversion of money to rural states from urban ones through the Highway Trust Fund, by reducing the overall spending on highway infrastructure, and by talking openly about removing a lot of infrastructure–could potentially even pull misfit senators from the right-leaning woodwork to join dyed-in-the-wool progressives like Sanders and Warren.

The changes that our laws have experienced since that time are laudable in their context but they need to go further than they have ever been imagined before. We already know that Sheldon Whitehouse knows how to give a good speech, and he certainly has the level of stamina needed for the task of filibustering something. He just needs to put these skills to the test and go on the offensive.

~~~~

Caro explains in his multiple volumes how the Senate has historically used its filibuster mostly to the detriment of positive social change, between Reconstruction and the 1956 Civil Rights Act blocking each and every attempt to make even the most gradual changes for black people and unions in the United States–with Johnson himself often at the helm of such retrograde senatorial actions. The development of an uncompromising activist movement for change alongside a real son-of-a-bitch that was willing to do what he had to do in government meant reform.

Caro explains in his multiple volumes how the Senate has historically used its filibuster mostly to the detriment of positive social change, between Reconstruction and the 1956 Civil Rights Act blocking each and every attempt to make even the most gradual changes for black people and unions in the United States–with Johnson himself often at the helm of such retrograde senatorial actions. The development of an uncompromising activist movement for change alongside a real son-of-a-bitch that was willing to do what he had to do in government meant reform.