“You say, ‘I haven’t left anything in Africa.’ …you left your mind in Africa!” — Malcolm X

“You say, ‘I haven’t left anything in Africa.’ …you left your mind in Africa!” — Malcolm X

With legitimized trepidation in each painful step, their soiled and bloodied feet, shackled with rusting iron at the ankle, marched from maritime prisons into a new reality — indeed a prison of sorts. This alternate reality entailed not only the enslavement of their bodies, but the degradation of their culture, erasure of their language, and evisceration of their spiritual lives. In the midst of our retentions we find our Black-selves in continual moments of spiritual reclamation. Was not our most precious loss that of our memory, or the knowing of how to remember? African somas, culture, and politics have, from the beginning, been the enclaves of white appropriation for both control and profit.

Management of black existence has always fused in compelling ways with white perceptions of black social and intellectual life. When Jim Crow minstrel performers stepped on stage, faces painted black with burnt cork, they projected an image of believable black life mainly because white-supremacist-created stereotypes, which were by definition of their construction, infused with meanings made palatable and profitable for white audiences.

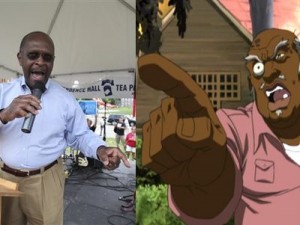

But what does blackface minstrelsy look like in the twenty-first century? In times past I have argued that it looked like commercial hip hop; I still maintain this. But the current presidential election cycle has witnessed the Republican party render to Herman Cain a national rostrum wherewith to carry out blackface-like buffoonery on a national stage. Yet, concomitant with his shameful exit we also witnessed the xenophobic cultural rejection of the All-American Muslim television series. And it has become apparent that the average white Republican voter is still quite comfortable seeing People of Color subjugated and subservient to political agendas that sustain the interest of a white male ruling class elite (the 1%) — and whenever this can be facilitated by a venal figure with a black face all the better.

Revolutionary Black intellectuals like Steve Biko and Frantz Fanon have long traced the provenance and explained the prevalence of white colonial ideology presented in Black face.

“In order to assimilate and to experience the oppressor’s culture, the native has to leave certain of his intellectual possessions in pawn. These pledges include his adoption of the forms of thought of the colonialist bourgeoisie.” — Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth

Here Fanon explains that the colonialist deemed it a cultural imperative to denounce the political presence of the native whereby to secure his compliance — or for the purposes of a 2012 election, his/her vote. Because politics do not stand alone, even the native’s image must be sequestered and re-managed, such that it be not merely arrested, but pressed into the service of a ruling class colonial order.

Representation is paramount in the shaping of America’s image in both domestic and international spheres. Given America’s wretched history (and present) with regard to race and class tensions, having an African-American figurehead as the face of the American empire is quite conducive to the international resistance of American hegemony. Indeed, President Obama has been metaphorically described as the opioid of the global masses.

But moments such as this, be they the intentionalities of a corporate plutocracy or mere organic products of the democratic maneuvers of concerned citizens, do have historical precedent.

Mary L. Dudziak, in her essay, Desegregation as a Cold War Imperative, states:

In the years following World War II, racial discrimination in the United States received increasing attention from other countries. Newspapers throughout the world carried stories about discrimination against non-white visiting foreign dignitaries, as well as against American blacks. At a time when the U.S. hoped to reshape the postwar world in its own image, the international attention given to racial segregation was troublesome and embarrassing. The focus of American foreign policy at this point was to promote democracy and to ‘contain’ communism. However, the international focus on U.S. racial problems meant that the image of American democracy was tarnished.

It is a naive to imagine that judicial altruism and situational ethics were the key factors in the 1954 U.S. Supreme court decision in favor of African-American educational progress in the Brown v. Board of Education in favor of school desegregation. With the nation in a postwar global rebuilding moment, the corridors of power would heavily rely upon the moral legitimacy that would result from perceived domestic racial cohesion. Since the U.S. military had used a segregated military machine in the war theater to battle forms of fascism it was imperative that the U.S. recast its own image. With the fabrication of this new image once again the black soma became the terrain upon which eruptions of power politics manifest themselves. School segregation was completely ignored for the entirety of the nation’s history, but suddenly in the postwar year of 1954 we are led to believe that the decisive conversation on black access to the nation’s educational resources was a paramount concern. This, no doubt, served as a hollow beacon of progress to much of the rest of the world that America had somehow bettered itself.

But are we actually in a post-racial historical moment? I strongly argue the negative. This grossly premature assumption of America as a new space, sanitized of institutional racial oppression, is insidiously dangerous. Why? Because it coincides with the delusion that we no longer need to do the work of race-based equity politics. African-Americans now have their very own President, and liberal whites were hugely influential in putting him in office. Is this not the narrative? A quick glance at any local, national, or even global socioeconomic statistical indexes where People of Color exist should be sufficient to disabuse any suspecting citizen of the misconception of racial equity, political or otherwise.

With the issuing of Cain and attempted silencing of All-American Muslim, the colonizers have declared that the scaffolds of power shall remain unchanged, while also maintaining a normative, though imaginary, representative aesthetic of America as essentially white and Christian. The deployment of Cain and bigoted denouncement of All-American Muslim signals yet another eradication of the political interest of those “othered.”

From intentional black invisibility at “Slut Walks” and “Occupy” protest, to black exploitation in the film The Help; from Herman Cain’s minstrel politics, to the ethnocentric disdain for Muslim-Americans, the colonial Right continues to vividly display to the nation and world what their sinister vision of the role those they seek to subjugate should be in this society. As we step forward into the new year we must remain sober and mindful of the necessity to regain the memories of who we were before we became something — or someone’s – else.

In 1935 a crucial piece of worker legislation, the National Labor Relations Act, was passed. Known as the “Wagner Act” after New York Sen. Robert Wagner, who in sponsoring the bill, reasoned that “Men versed in the tenets of freedom become restive when not allowed to be free.” The National Labor Relations Act constituted a seminal democratic moment in American labor and union organizing. Wagner’s bill, among other things, guaranteed protections for union organizing independent of company domination, the right to strike, boycott, and demonstrate against recalcitrant employers, and banned firing as a coercive tool to control union ranks.

In 1935 a crucial piece of worker legislation, the National Labor Relations Act, was passed. Known as the “Wagner Act” after New York Sen. Robert Wagner, who in sponsoring the bill, reasoned that “Men versed in the tenets of freedom become restive when not allowed to be free.” The National Labor Relations Act constituted a seminal democratic moment in American labor and union organizing. Wagner’s bill, among other things, guaranteed protections for union organizing independent of company domination, the right to strike, boycott, and demonstrate against recalcitrant employers, and banned firing as a coercive tool to control union ranks.