I suppose the aspect of conservative thought that most…puzzles? annoys? makes me laugh?…let’s say ‘puzzles’ me is the sense they seem to have that their ideas are somehow bold, and daring, and novel.

In fact, conservative ideas–low taxes, no regulation, no government–have all been tried. In fact, these ideas describe how government operated throughout most of human history. And they certainly describe the government of the US for most of its history.

Newsflash: these ideas didn’t work. We tried them, they didn’t work.

Let’s take the whole free market thing. *

One caveat: I am not an economist; I have no training as an economist. I do spend a lot of time reading economics blogs. I have five or six that I read regularly, another dozen that I read once a week or so. Definitions presented will generally be from Wikipedia, so they will be easy to verify.

Generally speaking, a free market is, more or less, unregulated. The idea is that all of the players–buyers and sellers–jockey back and forth in a rough-and-tumble so that prices come to reflect the best value as determined by the ‘market’, and resources are allocated efficiently and optimally.

For a free market to work, one aspect that must happen is that there must be robust competition among both buyers and sellers. Without robust competition, sometimes a buyer, more often a seller will gain a competitive advantage. The theory is that the competition will grind this advantage away, by underselling, a better product, or some such mechanism.

Competition will do this, but only under certain conditions. Competition is effective whenever the barriers to entry into a market are reasonably low. For example, a lemonade stand. My kid can put one up in a few minutes, undersell the kid who’s charging a buck a cup, and take away the price gouger’s market share in a heartbeat.

But what happens when barriers to entry are high? What about a mine? Or an oil refinery? Or a steel mill? Or meat packing?

Enterprises like these require huge capital outlays over a sustained period before they can enter the market. When they are able to do so, they are usually at a competitive disadvantage on price, since their operation may not have the efficiencies of scale that the established concerns do. In situations where barriers to entry are high, the tendency is for the operator with the most money will eventually win.

This was the Walgreens strategy: put up a chain store to compete with the local pharmacy, undersell the local, drive it out of business, then raise prices. Walgreens could afford to lose money on a lot of items because it was financed by a corporate treasury. Now we are in a situation in which there are virtually no local/mom-and-pop pharmacies. We have our choice of CVS (yes, it’s local, but hardly mom-and-pop), Rite-Aid, and Walgreens. Competition, but not overly robust. I suspect that Walgreens will disappear within a decade.

Even more to the point. In downtown Providence, we used to have the corporate HQ for several banks. Now, we have a satellite office for a single bank, a huge national conglomerate, that may, apparently, be pulling out of Providence.

These results are not surprising. This is what happens in a free market. It’s exactly what happened the first time we had unregulated, free markets.

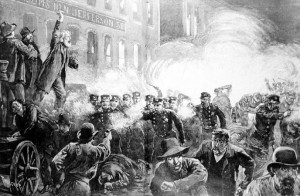

This occurred in the aftermath of the Civil War. The war provided a huge market for a lot of industrial products, so a lot of entrepreneurs took advantage and went into business to supply this market. Within fifteen years (give or take), most of these small businesses had vanished, having been swallowed up, or driven out of business by huge, vertically-integrated corporations, known at the time as trusts.

Not all trusts were monopolies, but many of them were. They bought, crushed, or drowned their competitors in a bath tub. This was considered a good thing; Rockefeller trumpeted his intention to ‘end wasteful competition.’ Even if they never quite attained a true monopoly–and it wasn’t for lack of trying– they dominated their markets.

Given the direction in which we are going, it is very important to remember what has happened. Given the death of Brooks Pharmacy, and Fleet Bank, and Hospital Trust, we need to recognize the path we’re on.

An unregulated, free market will generally end up in a monopoly in any situation in which barriers to entry are high. And they are high in most industries, in finance, even in a lot of retail operations.

And, just so there’s no doubt, below is evidence, demonstrating that our first experience with free markets ended up with most markets controlled by de facto monopolies. I don’t want it said that I make claims without offering proof.

I’m outsourcing this to a history book. The first edition came out in 1973; I’m quoting the second, from 1989. Either way, this stuff was written before the poisoned partisanship brought out by Newt Gingrich, when there was only one set of facts for everyone. Nowadays, there’s the actual set, and then there’s the set claimed by conservatives, in which tax cuts pay for themselves and stimulate economic growth, the economy has gotten worse under Obama, and we can drill our way to energy independence. More on some of those at a later date.

The Shaping of Modern America: 1877-1920 2nd Edition

by Vincent DeSantis Harlan Davidson, Wheeling IL, 1973 & 1989

Page 12…Just as Rockefeller had cornered the refining market, so Andrew Carnegie captured much of the steel market…

…From then on, led the field in the steel industry. He took bought out and took into his business Henry Clay Frick, who in the [1870s] had gained control of most of the coke ovens around Pittsburgh. Together they created a great vertical combine of coal fields, coke ovens, limestone deposits, iron mined, ore ships, and railroads….

Page 13…After Standard Oil Company set the trust pattern in 1879 other business enterprises of this form soon appeared. Before long most Americans were referring to all large corporations as trusts, a word that soon became loosely synonymous in the public mind with monopoly. Many important industries ceased to be competitive and in addition to steel, oil, and railroads similar combinations were built by equally forceful and ambitious entrepreneurs in other fields. [The list of such megalithic companies included t]he McCormick Harvester Company…American Tobacco Company…American Sugar Refining Company…while Philip D Armour and Gustavus Swift dominated the meat-packing business…

Page 14….As the American people watched the proliferating of trusts and millionaires, many became convinced that something had to be done to restore effective competition. There arose a popular outcry against monopolies….William W. Cook, an eminent corporation lawyer in New York, made a very sharp attack on monopolies in a volume on Trusts (1888) when he wrote:

(quoting Cook:)….. It is currently reported and believed that the “Trust” monopolies have drawn within their grasp not only kerosene oil and cotton-seed oil, but sugar, oatmeal, starch, white corn meal, straw, paper,… whiskey. rubber, steel,….wrought iron, pipes, iron nuts, stoves, lead, copper, envelopes, paper bags, paving pitch, cordage, coke, reaping and binding and mowing machines, plows, glass, and water works. And the list is growing day by day…

[ End cite ]

I hope everyone finds this both informative and convincing.

*Note: in comments on another thread, I posited that a free market and an unregulated market are not the same thing. The problem with comments is that they rarely reflect a considered opinion, since they often get dashed off in the heat of the moment. I regret that I made that distinction.

One topic that has been on my mind lately is the attempt to kill the 8-hour workday.

One topic that has been on my mind lately is the attempt to kill the 8-hour workday.