It’s hard to tax the rich at the local level. The area within the borders of a local community is small, and tax avoidance becomes a game to people with money. One need simply relocate a block across the border to smack back at most local popular efforts. I’m not saying it’s right. I’m saying it’s true. But there is a way to tax the rich in Providence, and get away with it.

It’s hard to tax the rich at the local level. The area within the borders of a local community is small, and tax avoidance becomes a game to people with money. One need simply relocate a block across the border to smack back at most local popular efforts. I’m not saying it’s right. I’m saying it’s true. But there is a way to tax the rich in Providence, and get away with it.

Taxing parking might seem like another consumption tax, but it’s not. It’s a Robin Hood tax– and one that even businesses should be in favor of.

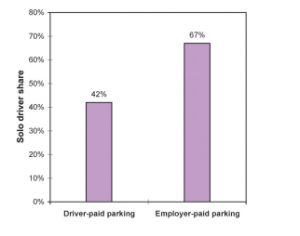

Why? A great piece on this appeared in Greater Greater Washington just a year ago. It points out, for instance, that the tax write-off for paid parking is larger than the one for transit, meaning that commuters who pay for parking already get a direct subsidy to repay themselves. But it also points out an even deeper point about the marketplace for (garage and lot) parking in cities.

Parking acts as an oligopoly more than many other markets, so (in garages and pay lots) it’s being sold at the highest bid it can sustain:

[P]arking operators are in the business to make money, so aren’t they already charging as much as the market will bear? In other words, if they could raise their prices when there’s a new tax, why don’t they just raise their prices now regardless?

Well, isn’t that true of all markets? But in most markets, competition drives down the prices of goods. If you’re making more money than a small profit over and above the cost of providing the service, someone else will enter the market too and try to undercut you.

Parking isn’t really a competitive market. In the short run, the supply of parking is absolutely fixed, and there isn’t empty land to turn into new parking in central DC. Also, many people also only really want to park in the building where they work, are going to the doctor, etc. and aren’t shopping around. That’s especially true when a company is buying parking for executives.

These factors make the parking market closer to a monopoly and/or oligopoly, and consequently, the pricing is more at the level that maximizes total revenue in the entire market, a level that’s higher than the perfect competition price.

The GGW piece cited a report commissioned by the Philadelphia Parking Authority in which garage owners complained that they would have to swallow any taxes levied on parking because there would be no one willing to pay a higher price for parking if they tried to pass it to consumers. When your business is an oligopoly, you’re already getting the best price you can, so a tax on your business just means a lower profit margin.

The GGW piece cited a report commissioned by the Philadelphia Parking Authority in which garage owners complained that they would have to swallow any taxes levied on parking because there would be no one willing to pay a higher price for parking if they tried to pass it to consumers. When your business is an oligopoly, you’re already getting the best price you can, so a tax on your business just means a lower profit margin.

Not everyone buys my notion that keeping the car tax where it is makes sense, though the fourth grade math involved in showing why that tax cut isn’t progressive is pretty straightforward. But everyone agrees (including me) that taxing a person’s car purchase is a type of consumption tax. If the reports on parking are correct, taxing parking lots (and garages) is not. The owner pays. And in Providence, the largest owner of parking lots is one of the wealthiest people in the state: former mayor, Joseph Paolino.

A business argument

I started my argument with the “tax the rich” pitch for the parking tax, because try as I might to convince people otherwise, I’ve still encountered friction from some on the left who think taxing parking is a flat tax on consumers (some people on the left even like the idea that parking taxes are a tax on consumers, saying that it’s a way to get the suburbs to pay their share towards city services they use). But if you’re a local businessperson, you might not care for this argument. Why shouldn’t you be concerned about the parking cutting and running? Isn’t a tax on parking going to drive people away?

Short answer: no.

Parking lots and garages aren’t golden geese. You can tax them, but like all things, their owners have the ability to try to evade taxation. But we shouldn’t be troubled by the this possibility because of the mechanisms involved. The PPA report cited within the Greater Greater Washington piece had garage owners complaining that while they would pay the cost of the tax in the short-run:

In the long run the story is quite different. An increase in parking taxes discourages the rejuvenation of aging facilities, the replacement of facilities lost to development, and the construction of additional facilities. Thus higher parking taxes will decrease the long-run supply of parking, will increase the cost to the public of parking, and will decrease profits to owners of parking facilities.

Further, should an additional parking facility be required, a higher parking tax implies that the facility will require larger subsidies to develop than it would in the absence of the parking tax increase.

Parking lot/garage owners can only escape the parking tax two ways: they can sell their land to someone else (who still, of course, has to pay the parking tax), or they can turn the parking into something that’s not parking. The PPA report reveals a lot. For instance, why would a city worry that it’s not able to replace “facilities lost to development”? Doesn’t the fact that development is replacing parking imply a healthy local economy, and that people are visiting that new development by some means?

In the second paragraph, we have the even more revealing “a higher parking tax implies that the facility will require larger subsidies to develop than it would in the absence of the parking tax increase.”

Indeed, in many cities, parking garages are subsidized by a city or state authority because the all-knowing hand of government thinks that people need better access to parking above all else. (If you’re a local business owner and wondering why the all-knowing hand of government doesn’t have free money for you instead, you’d be right to wonder).

The truth is, parking lot/garage owners have three choices: pay up (and swallow the cost), develop something better (and make the neighborhood more desirable), or sell (at a cut-rate price, making it easier for the next person to develop something). As a business, none of these should worry you, because they all represent the neighborhood becoming healthier for your enterprise. Lower taxes or lower land prices will both mean more of the development that supports transit, and will also add to the tax rolls, so even as the revenue from the parking tax slowly dissipates, the problems that creates solve themselves.

Give it all back

If parking owners being unable to increase their prices, and the flat out arrogance of parking owners getting government hand-outs isn’t a good enough business argument, then how about this: the best use of the parking tax in Providence would be to directly lower other taxes.

Even in a hypothetical case where parking was more expensive, the collected money would equalize that shift in price, and returning the money to local businesses through lower taxes would help them compensate with better services or lower prices. But the more likely event is that parking prices will stay the same while allowing your taxes to go down. Who could argue against that?

You’re getting taxed anyway

The strongest argument against the parking tax is to ignore all the data and examples I laid out, and just cry Chicken Little. OH NO, EVERYTHING WILL COST MORE! OH NO, THERE WILL BE PARKING-GEDDON! OH NO, STOP TAXING US!

The problem with this argument is that you are being taxed.

Though rates technically went down on some taxes in the mayor’s budget, the amount paid has gone up on just about everything. One of the newly raised taxes is the “meal and beverage” tax.

If we were trying not to tax parking because we were worried it might chase people away from local businesses, was taxing restaurants instead the way to go?

Give it to me in a paragraph

Parking is a weird oligopoly, and the owners are charging you as much as they can. Taxing them more doesn’t actually allow them to pass that on to you, because they’ve already maximized their price. So parking taxes are a tax on rich people who are speculating on land. Parking taxes encourage those people to turn that parking into something else, but in the meantime, the city collects revenue that lowers your taxes. The city is “considering” taxes on parking rather than “implementing” taxes on parking because they’ve got cold feet about taking on one of the richest people in the city. You should tell the city government that you want a tax on parking, because if they don’t tax parking, they’re going to tax your house, your apartment, the restaurant you go to, and everything else first.

Tax parking.

]]>Rep. Regunberg, who won the 4th District (East Side of Providence) with 83% of the vote, sent this statement to RI Future:

It is important for economic development, sustainability, and quality of life that our city create incentives that will lead to fewer cars on the road. Most residents familiar with Providence will recognize the incredibly negative impact on downtown of our far-too-many surface parking lots. We know the economic benefits that come with higher density land use, yet our current system incentivizes the spread of these unproductive developments which hurt pedestrian byways, impact our small businesses, and mar our city’s beauty. I believe an intelligently-structured parking lot tax could spur higher-density development and help build a more sustainable community.

Regunberg notes the importance of emphasizing the “lot” part of the tax.

A parking tax would charge a fee to surface lots in the city, and 100 percent of that fee would then be returned to residents and businesses as a tax cut. The exact type of tax cut is up for debate, but I’ve suggested reductions to property taxes targeted to areas nearest the lots.

A parking tax would charge a fee to surface lots in the city, and 100 percent of that fee would then be returned to residents and businesses as a tax cut. The exact type of tax cut is up for debate, but I’ve suggested reductions to property taxes targeted to areas nearest the lots.

Because the city’s tax structure offers lower taxes to parking lot owners than other businesses, owners are disincentized to redevelop lots, and building owners can even be encouraged by the tax code to knock down buildings for more parking lots. This creates a death-spiral for the city.

Ethan Gyles, Regunberg’s general election opponent who took 17% of votes, has also indicated support for a parking tax in December 8th Tweet, saying that he was behind the measure so long as it “is written such that the city must lower other regressive taxes” in its place.

]]> “With a baby and work, everything else is pretty hectic,” said Andrew Pierson, when the Oak Hill, Pawtucket resident was asked why he often drives to work instead of taking RIPTA.

“With a baby and work, everything else is pretty hectic,” said Andrew Pierson, when the Oak Hill, Pawtucket resident was asked why he often drives to work instead of taking RIPTA.

But when Pierson drives to work he never does so solo. He and his wife “carpool approximately three to four days a week.”

Pierson is rare among American drivers, 90 percent of whom make their trips to work alone. Among carpoolers, though, he’s pretty typical. The majority of carpoolers share their vehicles with family.

“Ironically, we have some of our best conversations in the car,” he said. “And when we really need to talk about something and can’t find any time – the car seems to be the best place. Most people thought that having a baby would force us to purchase another car but it really hasn’t been much of a change. We chose a daycare close to one of our offices and she [the baby] is basically part of the carpool.”

One reason families are the center of carpooling is the inherent power inequality between the owner of the vehicle and the non-driving partners. Carpooling is intimate as much because it asks us to share our vulnerability with a stranger as because it shares physical space.

Carpooling to a place with paid parking is different though. I know this because I’ve been in such carpools to Boston at hours when the T doesn’t run. When there’s parking to be paid for, the passenger is king. They have something to bargain with: half the parking fee.

- Seth Yurdin: Parking tax ‘great idea for downtown’

- How to structure a parking tax

- Providence should pass a parking tax

It’s no real revelation, of course, that the cost of things like gas or parking matter to whether or not people choose to share a car. In 1980, when twice as many people (20%) carpooled to work, the price of gasoline was equivalent to $6/gallon. I’m making a different point entirely, which is that in these situations, the power of the lesser partner is amplified. This may be a major key to stretching carpooling beyond families the way it began.

On a commute, a driver of a carpool is providing a real service, but asking for anything can feel crass. The passenger is reaping a real reward, but might feel like a potluck attendee with no food if he or she didn’t offer something to the driver. Because conversations like these force people into acknowledging difference, some people might rather avoid the whole scene.

If the parking tax brings downtown parking from $10 up to $14/day, getting just one passenger should lower that to $7. When a third person is in the car, driving to downtown would be comparable to a round trip bus commute with transfers (just under $5). If carpooling commuters get more passengers than that, they actually beat the cost of transit, with or without transfers. Meanwhile, they save money on car maintenance, gas, taxes for road repair, reduce congestion and pollution, and help put money back into the downtown instead of surface lot owners’ pockets.

- Seth Yurdin: Parking tax ‘great idea for downtown’

- How to structure a parking tax

- Providence should pass a parking tax

Pierson catches a ride with a coworker to meetings about once a week, something he says makes his shared car situation with his wife possible. This has been a real benefit to his family.

“Why waste ten grand on a depreciating asset when [my family and I] can get exercise, enjoy our commute more and spend a few extra minutes together,” he wondered.

Pierson is fairly conscientious about the role of cars in Rhode Island, working recently to encourage Pawtucket to make itself more bike- and pedestrian-friendly. He responded to a tweet asking for carpool interviews. I know Pierson and work with him on some of his goals.

With a higher parking tax, people who never thought about city planning or walkable cities will have it front and center, and they’ll save money because of it too.

]]> “The parking tax would be a great idea for downtown,” was Providence City Councilor Seth Yurdin’s “initial response” when I asked him about it at a recent Bicycle & Pedestrian Advisory Commission.

“The parking tax would be a great idea for downtown,” was Providence City Councilor Seth Yurdin’s “initial response” when I asked him about it at a recent Bicycle & Pedestrian Advisory Commission.

But he also said he’d need more information before knowing if it would be the right tool for Providence. He said he worries it might be regressive. Our conversation was informal. I didn’t identify myself as a blogger/journalist, but I did introduce myself as, and was referenced several times during the meeting, as a transportation advocate.

Anything that would stop land-banking in Downcity is a good idea, Yurdin said. Land-banking is the process of demolishing buildings and using the vacant land as commercial parking lots in order to take advantage of the way the city’s tax code works: a parking lot owner can claim their lot isn’t worth much, while charging an arm and a leg to bring excess cars into the city.

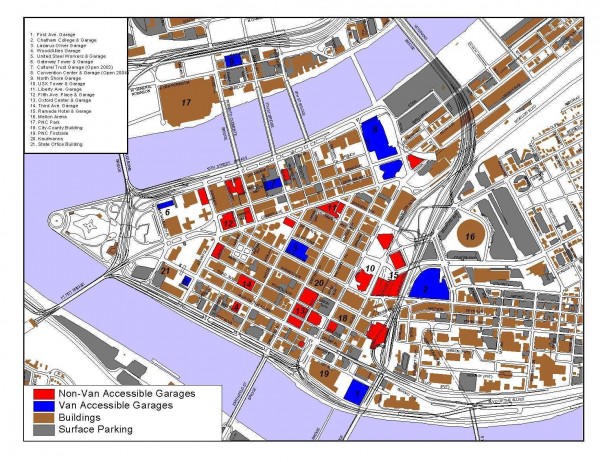

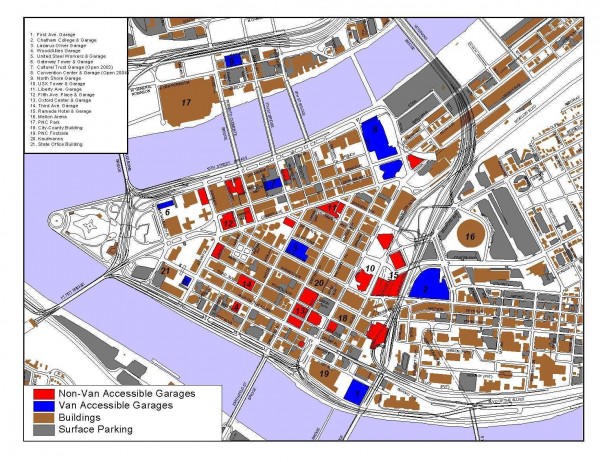

Support from Yurdin is important because his ward covers the areas of the city that have the lion’s share of commercial parking lots: Downcity and College Hill. A tax on commercial lots, either by revenue or per spot, would be the most likely form that a parking tax would take.

Yurdin said he had “equity concerns” about extending a parking tax beyond downtown, although I think we should push him on the City Council to allow lots located in College Hill to be taxed as well. I feel strongly that colleges shouldn’t get a special status for their parking lots. (For the record, taxing parking is not regressive, although the federal parking tax benefit–essentially the opposite of a parking tax–is). Splitting the difference with Yurdin and taxing only wealthy areas of the city would be fine with me, though, especially since those roughly correspond to the most transit-served job centers in the state.

Yurdin wondered aloud whether a tax rebate on property taxes would actually lead to more affordable housing in the city (“What landlord have you ever heard of who gives you a break on your rent because his taxes go down?” –Touché, Mr. Yurdin). This has had me thinking pretty hard for a response. Charging a higher tax on rental properties indisputably leads those properties to be less plentiful and more expensive than they might otherwise be, but correcting the supply issues caused by bad city policies would take time. Who’s to say one’s landlord isn’t happy to pass on extra taxes when they come his way, but doesn’t care to do the reverse? It’s a quandary. In the long-term, removing exclusionary zoning would tend to put landlords in competition, but we should want tenants to get their money now.

A conversation should be had about how to split revenues in a way that is fair and actually results in tenants getting a fair share. One proposal worth exploring would be to have the city cut a check to tenants directly, rather than having their landlord serve as an intermediary. I haven’t researched how easily that could actually be administered, though. Another option would be to cut the tenants’ tax, but focus initial returns as a credit towards building repairs that can’t just spent away. I like the idea of lowering property taxes because I value infill and affordable housing as priorities, and because I think these goals elegantly replace tax base just as quickly as the city loses parking revenue, but I’ve also discussed the idea of trading a parking tax for part of the city’s car excise tax, and debatably that could be bargained over to achieve equity goals as well.

Seeing the city tackle either the quality or cost of housing would great.

More on A Parking Tax for Providence.

]]> There are several ways a parking tax could easily be implemented in Providence.

There are several ways a parking tax could easily be implemented in Providence.

In a previous post I introduced the concept of a parking tax for Providence. This post explores five such options for implementing and collecting parking taxes. Future posts will demonstrate how much revenue can be raised, how it could offset other city taxes and what social benefits will result.

A revenue tax on commercial lots

The easiest way to enact a parking tax would be to pass a tax on the revenue from commercial lots – that is, the ones that charge a fee to commuters in the downtown. This is the tax collection model in Pittsburgh, where lot owners are expected to keep receipts of the revenue they collect and pay a 40% tax on that revenue.

There’s a range of effects that could take place with this kind of tax. If demand for parking was really high–no one who already parked stopped parking–lot owners would be in a position to pass 100% of the tax on to customers. So, imagine for instance that your normal fee is $10/day. That fee would become $14/day.

If demand for parking was really low–everyone, say, decided that it was not worth it to park–then lot owners would have to eat the tax entirely themselves. Lot owners pay around $0.60 per spot per day in taxes, so paying a $4 a day tax would be left with a strong incentive to either sell or repurpose their land. Even if a healthy number of people still chose to park, lot owners might be incentivized to reduce the size of their lots in order to stop having to eat so much of the tax. This would reduce parking tax revenue (and parking supply) but would increase tax receipts from buildings (and more importantly, would mean that there’d be way more cool things to visit, places to live, and jobs to work at in the downtown).

The reality is that demand for parking would fall somewhere between these two extremes. Lot owners might feel some pressure to take on some of the tax as a profit loss, because at $0.60 or $0.70 a spot in property taxes, a $10/day fee minus x amount of additional parking tax would still leave them a healthy profit. There would probably be enough demand for parking that commuters would pay some of the tax themselves in higher fees, too.

The big thing to remember about a revenue tax is that if a parking spot were free in the city, the lot owner would pay no tax. If the spot were on the market, but didn’t “sell”, i.e., no one parked in it, it would also be tax-free.

A “per spot” tax on commercial lots

A tax on lots “per spot” could be applied to commercial lots. This varies from the revenue tax in that the city would decide a fee for each parking spot that did not depend on usage. In our 40% example, $4 would be the fee on a $10 parking spot, so perhaps the city would just say to lot owners, “if your spots are on the market, there’s a $4 tax. 100 spots is $400 a day tax, no matter who uses them.”

Lot owners in this scenario would face a slightly different situation, and I imagine this tax having a stronger effect on reducing lot size as well as a greater immediate effect on reducing the profitability of parking lots. For instance, if a lot owner has 20 spots open on a given day, that that’s an $80 loss. If it comes to 10 AM, and those spots aren’t full, he or she may give them away for $4 each, just to break even on the tax. A lot owner won’t accept that position for long, though. He or she will start to look at the bottom line and think about how to get rid of parking spots that are typically not full.

The other advantage to the “per spot” tax is that it’s much easier to account for. The city uses Google Maps, and counts, and issues a bill. In order to prevent fraud in revenue tax situations, cities often use some kind of a smart card, so that there’s an unchangeable paper trail. But none of that would be necessary for a per-spot tax.

Per spot taxes are favored by the Victoria Transportation Policy Institute, covered here on Streetsblog.

A “per spot” tax on all parking lots

A per spot tax also opens up the possibility of taxing all parking lots in the city, not just those that charge a value for their parking. I really think this is the best option, but I also realize that there are political difficulties to implementing it.

A disadvantage to only taxing commercial lots, whether in the “per spot” or “revenue” model is that it creates an arbitrage around the value of parking on free lots. An arbitrage is when something is selling for one price one place, and a different price in another. It’s the kind of thing that day traders take advantage of when they’re doing frivolous trades back and forth to make profits without creating things. Arbitrages can also be a legitimate tool in a marketplace, helping people to make sense of what the price of something is, if information is shared fairly. You don’t want to go out of your way to create one, though.

Imagine you’re the owner of a business. The cost of paving a flat parking lot might be very small to you, both in upkeep and taxes (property tax assessments would say that the lot wasn’t really worth anything). If you give your spots away to your workers for free, your workers are super excited. To them, this is a $14/day value, because their access to parking is solely through what they can buy from a commercial lot, and what is given away to them by an employer. But you, the employer, have a great deal more leverage. You’re not really giving your workers $14/day at all. You’re taking advantage of a tax loophole to turn a tiny investment into a huge benefit for your employees (and you). That might sound well and good if you’re the employee, but it circumnavigates the purpose of the parking tax, so the more we can do to stop that problem, the better.

A tax on free parking would tend to affect big box stores disproportionately, which in my opinion would be both fair in a market sense of the word (pay for what you use) and in a share-the-wealth way. A business like Home Depot is imposing a lot more cost on the city through all types of infrastructure than, say, Adler’s Hardware store on Wickenden. An African grocery store on Cranston Street in a bottom floor of a three story building is costing the city much less than a Stop & Shop. And you’ll notice, although there would be exceptions, that most of the smaller footprint businesses tend to be independently owned. It’s also the case that some Dunkin Donuts stores or other chain stores might get thrown into the mix. But for the most part, the tendency would be that large chain stores would have huge parking lots, and local businesses would have modest parking lots, or no parking at all.

Another really big advantage to a tax on big box lots is that, so long as the city allows it, big boxes may not necessarily object to having somewhat smaller lots. There was an absurd case of a municipality requiring so much parking that even Walmart asked for a variance to get out of the requirement. Parking requirements for big box stores is usually set to some imagined peak demand, usually Black Friday or Christmas Eve, and transportation advocates have even gone out on these days to take pictures and show how overabundant these parking supplies are even for that purpose. So big boxes would have a choice: pay a tax on parking that’s excessive to begin with, or lease out the space and build some more stores. As a mental exercise sometimes, when I’m in a really hopeless looking over-large strip mall, I like to imagine what it would look like if piece by piece, little bits of the parking lot were gradually turned into neighborhood extensions. All in all, many big box stores aren’t even necessarily that awful in and of themselves. In reduced lots with things built around them, they could be shopping hubs for a much more connected population.

Smart Providence voters would support the parking tax on big boxes also as a means of leveling the playing field. Providence has a minimum business tax, which means that you’re paying a fairly high premium just to start out, whether or not you’re successful. Lowering or eliminating this kind of tax, going to some kind of percentage tax, and having a surcharge on parking space could change that scenario. What a big box is doing is essentially wielding a huge weapon of amazing, awe-inspiring car access, but without having to pay for any of what makes that possible (environmental damage, loss of walkability, increased sewage runoff, increased sewer infrastructure, hundreds of thousands of dollars per intersection of signals, wider roads, etc., etc.). Small businesses are essentially paying those costs–the costs of taking away their own customers.

A per spot tax on all parking lots could be set up to have a deduction of sorts for the first X number of parking spots. I don’t really think this is necessary, because the net reality of a parking tax would be to return more property taxes to small businesses and residents than those small businesses or residents pay out, but we also have to be aware that many people don’t like to dive into complicated multivariable math, and if doing this makes it simpler for people to count the pluses and minuses in their life, then fine.

I wrote a lot about the concept of value-per-acre at EcoRI News some time ago. It’s an idea put forward by Joe Minicozzi, and I think people interested in building an equitable growth model that’s good for the environment would do well to familiarize themselves with his work. This also helps to explain this tax model more.

Residential parking

A concern is parking in shopping areas. How would a parking tax affect residential areas? I think the tax models above would have very diminished value in most residential parts of Providence, because in those areas the value of parking may be minimal compared to the effort of passing a law. However, there are parking policies we could institute that would help residential areas. Those I’ve loosely based off of parking guru Donald Shoup of UCLA.

A big tool would be giving renters a cash-out option on parking. As a beginning to this, renters who have a garage as part of their lease should be able to opt out of the cost of the garage if they don’t want to use it, because garage parking affects housing affordability. A rent of $1,000 for an apartment that includes one garage spot can be broken down into $600 for the room, and $400 for the garage. A lot of residents will be happy to pay for the garage if they use it, but forcing landlords to treat these as separate things will open up parts of the downtown to people with less money who don’t drive. The landlords would be free to open unused spots on the open market, which would also help get rid of surface lots, by competing with lot owners. There would be no tax on this residential parking, because forcing it to be treated as a separate commodity would have a downward effect on demand.

Many parts of Providence have driveways, a legacy of on-street parking bans of days of yore. It would be a real gain to get rid of some of those driveways, or at least people to put raised beds above them. Other driveways could be converted into “granny cottages” to add housing. But the reality is that driveways are just not worth anywhere near as much as garage spots, nor are they the severe blight on the city of surface lots. This might make a cash-out hard to calculate. Instead, why not nix the existing on-street parking permits entirely (Do I hear a huzzah?) and trade them for an equal permit cost on driveways. Parking on the street would be free in most residential areas. Think of this as a mini-credit towards green space. Homes that decided to park on the street would and use their driveway for raised beds, or that pulled up the paving on their driveway, or built a building extension into the driveway, would not pay the tax (although the building extension would be weighed into property taxes). Getting people to park on the street in residential areas would not only help green space, but would also slow down speeding. I know that getting rid of some of the driveways in Mt. Hope would make crossing my street much more pleasant.

For streets that got protected bike lanes (mostly arterials), the parking tax would be nixed, and no driveway tax would be issued either. The logic is that in some areas we may have to remove parking lanes to create safe biking, and if you’re not getting a parking spot out front of your house, why should you pay?

Donald Shoup talks about “right pricing” (click for video) parking, which is really just an issue in places where parking is in high demand (the idea is the lowest price that still keeps a couple spots free). Most residential areas are not going to run low on parking no matter what the price, but some that are near shopping districts would benefit from parking meters to impose a price on visitors and ensure that residents have a place to park. To make things simple, residents would pay meters, but the meter money would be taken off their property taxes. This also solves a big problem with the parking permits we have now–they’re by ward. What happens if you want to visit someone? You can’t park away from your house without worrying that you’ll get a ticket. This way when I visit you I pay, and when you visit me, you pay, but we both get 100% of the money off the taxes we were going to pay the city for our house. And. . . and. . . we’ll be able to find a spot.

A land tax

A land tax is not a parking tax, but it’s worth talking about, since my proposal for a parking tax is sort of a modified land tax. A land tax says that you should pay not just for the building you build on top of a piece of land, but also for its location and the type of zoning it has. So, for instance, a vacant lot is a particularly galling case of an owner flaunting the lack of a land tax in Providence, because since we only tax property value, it’s assumed that the prominent downtown location of a lot is worthless when it’s anything but.

The concept of a land tax gets slightly complicated though, and although I’m a believer in land taxes overall, I want to avoid some of those complications by going straight for a parking tax. For instance, what do we do about green space? If you own a house with a huge yard, should you be taxed extra just for the fact that your land is a half acre instead of a quarter acre or tenth of an acre? I think a lot of people might find this concept troubling, because even if it’s not our yard that we’re talking about, we just kind of like grass and trees, etc.

By the same token, what if we decide that downtown is worth a lot more in land taxes than some other place, but we find that some historic buildings don’t produce enough revenue to pay what they would pay as 20 story buildings in that location. Do we want to create a situation that might push them out, or encourage demolitions? A clever administration could draw exceptions and loopholes into a land tax to try to close the problems with this, but I just prefer going around it entirely and focusing on what we want to get rid of most: surface lots.

One concept that works really well from a land tax that we should use is modifying our tax structure based on location. I think a really good rule of thumb should be that a parking tax should be highest in places within 1/4 mile of frequent transit, a bit less 1/2 mile from frequent transit, and nonexistent where transit is nonexistent. Providence City Council could also choose to tax parking lots that are a adjacent to the front of a building differently than it taxed parking in the back of a building, since the latter has less of an effect on neighborhood walkability.

In the next piece I’m going to consider how suburban and rural areas of Rhode Island could best respond to Providence imposing a parking tax if they’re interested in saving their residents money. Stay tuned!

]]>

Cities with less parking do better economically and environmentally, so getting Jorge Elorza firmly behind a parking tax should be one of our top concerns.

When asked whether he would support a parking tax during his administration, Jorge Elorza blew a dog whistle for potential supporters and opponents, saying in effect “not now.” On balance, Elorza’s reply makes me confident that the mayor-elect’s administration will institute a parking tax if Providence voters push him on the issue. A parking tax is one of the most important economic development and transportation initiatives that the mayor could take on, and progressives should ready themselves to ask for its passage.

I feel comfortable trumpeting the impending passage of a parking tax because of the particular caveats Elorza had with passing one. He at first said “we can’t adopt it right now”, but then added this:

The larger reality is that our citizens are already over taxed, and we can’t consider adding anything new to that burden. Over the long term, if we can manage to lower some of the other taxes – property tax, the car tax, etc. – I would consider a parking tax, because it’s much more progressive tax. First, it requires visitors to the city to share a portion of the tax burden, unlike the property and car taxes, which only impact residents. It also incentivizes other forms of transportation and ride sharing. (my emphasis)

Why do I think such a seeming non-answer is hopeful? Because the caveats are built into the proposal itself. Proponents of a parking tax ask that the city tax parking, and use 100% of the revenue to reduce other taxes. A parking tax means a tax cut on your house or apartment. We should take this as a yes and start pushing Elorza to keep his promise. Yours truly much prefers a lowered property tax to a lowered car tax for obvious reasons, but even a lowered car tax in return for a parking tax wouldn’t be a non-starter.

Pittsburgh currently has the highest parking tax in the country, at 40% of value, and it brings in more revenue than income taxes for the city (I would favor a parking tax arrangement that also taxes “free” parking–see article here–but getting commercial lots to pay a tax would be a start). Allowing Providence to tax parking could create the right balance that would both favor development and create a fairer environment for ordinary people.

As a type of de facto carbon tax, a parking tax works much better than, say, the gas tax, because if the mechanism that discourages driving works to actually reduce vehicle miles traveled, the result will be an economic situation that favors less driving even more. When drivers reduce their vehicle use, gasoline tax revenues are reduced, and programs like public transportation budgets suffer. Raise the tax to get more revenue, and driving is reduced yet again. But drivers who shun the parking tax by driving less will leave lot owners with less revenue, not transit agencies. The owners of lots, who previously may have calculated that it was worth developing nothing and taking a fee each day from commuters, might get a different idea. On the other hand, if drivers continue to park, the city collects revenues which can be put into property tax reductions. This, too, would encourage infill. So we have a positive feedback loop.

A parking tax dodges some of the objections people could have to a land tax. Residents with big yards don’t need to worry that the city is going to try to punitively charge them for green space*. And a parking tax would favor smaller businesses that often struggle to compete with big boxes, but which produce more benefit with less cost to cities. Big business need not even worry so much, since catching up would simply mean following the set of incentives the city is offering. Got parking you’re not using? Build another store on it, or lease it out to developers for housing.

The parking tax, unlike the car excise tax, has the advantage of taxing non-residents as well as residents, making it a more progressive way of pricing the cost of automobiles to society. This set up also answers a critique I’ve heard of the car tax, which is that some people may find themselves unable to give up a car due to long exurban commutes out of the city. A parking tax would inherently tax those who work in the urban core the most, meaning that city residents who normally drive from nearby neighborhoods to their jobs in the core out of convenience would likely be the first to change their habits and use other methods to get to work, while those who live on the South Side but work out in the boonies at a Walmart would be unaffected. Since a parking tax would raise the effective cost of driving to the core while lowering the cost of living there, many residents would experience the parking tax as a break-even tax or even a tax reduction.

A parking tax, by lowering property taxes, would encourage infill. Currently, the city frequently awards tax stabilization agreements (TSAs) to downtown developers to help ameliorate the city’s huge parking crisis and get new building stock. TSAs have a built-in logic that makes economic sense, but residents nonetheless have good reason to feel annoyed at them. With very high property and commercial taxes (Providence has the highest commercial taxes of any city in the country, in fact), it just doesn’t make sense to develop parts of Downcity without some reduction in cost, so TSAs get something where the city might have gotten nothing. But instituting a parking tax will help to lower these overall tax burdens in a more equitable way. Now, not just those with connections to City Council, but also renters or homeowners in every neighborhood of the city, will see a reduction in their taxes.

The parking tax should also please progressives because it asks for as much as it gives back. TSAs fundamentally lower taxes for certain people without any immediate short-term plan for revenue. In a city facing yet another fiscal shortfall in the coming year, that’s a problem. Raising revenue for the city from a parking tax while giving that revenue back would be a more balanced approach.

The immediate challenge for the parking tax will be getting a City Council resolution in favor of its passage. Based on my best advice from talking to a variety of city and state officials, I understand that the legislature would have to give Providence authorization to institute a parking tax. I know there are some who have said they’re interested in helping with this effort, but first City Council has to move forward.

I’m going to be working with City Council to build support for a parking tax in the coming year, and I hope that RI Future readers will join individually and as organizations to call on Council and the mayor-elect to pass it.

~~~~

*I don’t contend that this is something that really happens under a land tax, as, in fact, land taxes often effectively act as parking taxes, but what I would say is that this clarifies the issue in voters’ minds.

]]>