On Monday a group of people will sit down at Open Doors and talk about Senator Whitehouse’s bill to create a federal parole system.

On Monday a group of people will sit down at Open Doors and talk about Senator Whitehouse’s bill to create a federal parole system.

The bill is hailed as a “prison reform bill,” and passed the Senate Judiciary Committee; a clear indication of the shifting tide on political ideology over the past few years. This ebbing of the ‘Tough on Crime’ rhetoric includes many people who were bipartisan architects of the prison industry itself, and jibes with Attorney General Eric Holder’s public desire to make the system “more just.” Of course, this indicates he believes it is currently less just than it should be. The voices you have heard over the past several years talking “reform” are the result of those of us who have been peeing in the pool long enough to warm it up so everybody can get in. Even if just a toe, they’re getting in.

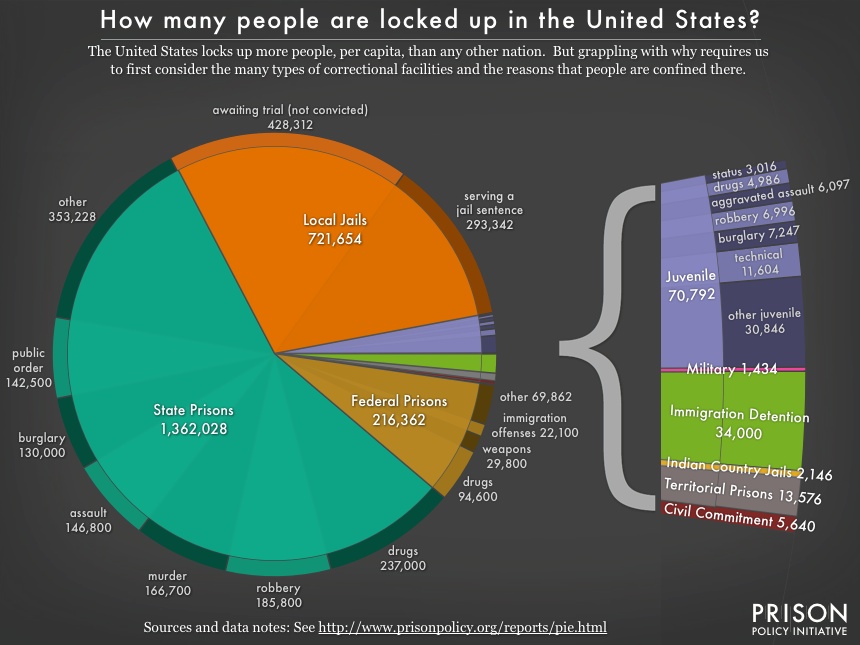

This prison reform bill is quite overstated however, and falls well short of what the public is truly calling for- something Senator Whitehouse appeared to be going for with his former bill to create a commission of experts that would propose a national overhaul. The Recidivism Reduction and Public Safety Act of 2014 will have no impact on state prisoners, where six times more men, women and children are serving prison terms than under federal law. Furthermore, it will have no impact on the 722,000 people currently sitting in a local jail- a snapshot of the 12 million who cycle through that system. Its not easy for the feds to control state crime and punishment under the law, but like anything else: the feds could put strings attached to all the financial subsidies of a bursting prison industry.

This prison reform bill is quite overstated however, and falls well short of what the public is truly calling for- something Senator Whitehouse appeared to be going for with his former bill to create a commission of experts that would propose a national overhaul. The Recidivism Reduction and Public Safety Act of 2014 will have no impact on state prisoners, where six times more men, women and children are serving prison terms than under federal law. Furthermore, it will have no impact on the 722,000 people currently sitting in a local jail- a snapshot of the 12 million who cycle through that system. Its not easy for the feds to control state crime and punishment under the law, but like anything else: the feds could put strings attached to all the financial subsidies of a bursting prison industry.

What’s in it for Rhode Island?

The bill will impact a few Rhode Islanders and tens of thousands of people nationally who will now gain an opportunity at parole, but what the bill deems “Prerelease Custody.” They can do this by engaging in what we once considered educational and rehabilitative programming, but the bill deems “Recidivism Reduction” programming. This wordsmithing is no different than calling oneself a “Pre-Owned Car Dealer” (which is what they do, these days). To assess the merits, it is important not to be distracted by shiny new things.

The Good Time credits earned by federal inmates are not for everybody, and they are not time off one’s sentence the way they commonly are applied to state custody. Furthermore, parolees in halfway houses and on electronic monitoring pay for their own incarceration, sometimes to their own financial ruin. Thus, this is not a handout by any means yet does pose a possibility for the prison system to generate additional revenues from the predominantly low-income and struggling families trying to rebuild a life after prison.

Slavery by another name: Prison Labor

The bill prioritizes an expansion of prison labor, viewed as a form of rehabilitation and method of reducing recidivism. It is impossible to discount the value of having a prison job for the prisoner, even at 12 cents per hour of income. However, it is difficult not to think of one ominous phrase “Arbeit Macht Frei” infamously posted over Camp Auschwitz. Work makes you free. A prison worker gets time off their sentence, and this bill calls for the Bureau of Prisons to review in what ways the prison labor force can be used to make goods currently manufactured overseas, so as not to cut into the free labor pool.

The use of prison labor is controversial, to say the least. Some critics have called for a repeal of the 13th Amendment, which provides for slavery of anyone convicted of a crime. This provision allowed for the massive “convict lease labor” that built a considerable amount of American infrastructure after slavery was abolished. The legal framework that is said to have freed Black America also allowed for people to be rounded up and placed, fundamentally, back where, essentially, Black America had been liberated from.

Today, prison labor exploiters capitalize upon incarcerated people’s desire to stay busy rather than sit on a bunk all day. This sort of macro-management does not take into account the relevance of a worker’s feelings. People in the system are treated with the callousness of lab rats, which may be all fine in the punishment phase, yet counterproductive when doing anti-recidivism, rehabilitative, or reentry programming. Does Johnny have a job, a home, or health care? Check. The assessments never ask if Johnny is happy.

Reentry programming still being run by those who have never reentered

The Recidivism Reduction and Public Safety Act also focuses on reviewing current reentry programs and developing federal pilot programs based on the best practices. This is an admirable goal and an obvious step to take. The challenge is to correctly assess best practices, and then implement what might feel controversial. For example, many policies prevent formerly incarcerated people (FIP) from affiliating with one another, and yet this bill references mentorships. It is likely that the drafters visualized a well-intentioned citizen with no criminal involvement and demonstrated success showing the way to someone getting out of prison. Yet such a person has very little to offer in the sense of mentorship. An FIP often grows frustrated with social workers, mentors, and probation officers who feign to understand the pressures of post-prison life. The best mentors are role models, and in this scenario will be FIPs.

This legislation also puts a considerable focus on risk assessment models, as though they are a new pathway to success. However, these tools have been in use for decades, and nowhere in the bill is there a call to study their individual accuracies. Rhode Island, for example, uses the LSI-R scoring system. The irony of in-custody assessments, that take all of forty five minutes to conduct, then a few minutes per year to update, are how a high-risk prisoner can be a low-risk free person. Conformity in prison does not translate to the attributes required for successful living in free society. Furthermore, an antagonistic interviewer will likely invoke anti-social responses from a someone, thus along with their past criminal activity, setting the foundation for an entire course of reentry opportunity.

The fundamental flaw in many prison-related programs, particularly after the Bush Administration’s Second Chance Act, is the lack of involvement of affected people. The roundtable at Open Doors consists of their director Sol Rodriguez, DOC Director A.T. Wall, chiefs of the Providence and State police forces, the federal and state public defenders, Crossroads (a homeless shelter), and possibly someone(s) that Open Doors has been working with. The stakeholder list is upside down. Law enforcement does not have a stake in my successful reentry. In fact, they have a stake in my failed reentry- so yes, they are a stakeholder, but in a perverse manner. After being punished by a group of people, be it months or decades, there is no trust in place for the punisher to then be the healer. For the government to believe otherwise only underscores these misconceptions and miscommunications of trying to reposition the pawns on the board.

The second class citizens

The public defender and Open Doors are not run by people who have “been there, done that.” When efforts like this use those agencies to speak for a disempowered population, it only further delegitimizes people with criminal histories, only furthers the second-class citizenship, and continues to render us without a voice. Rather than confronting any counter-narrative an FIP presents to policy reform, we are often disregarded as unruly, unmanageable, or uncivilized. Yet we are the ones seeing our selves and our family members dropping off the map, figuratively and literally, every day. Reducing recidivism and increasing public safety can only be done by a full restoration of people to being equal and valued members of society, especially the overwhelming number who are (on paper) “citizens” of America.

Efforts like these are akin to watching someone fish without bait. As expensive a boat, pole, and hook they use… they just don’t realize why the fish don’t simply leap onto the hook.

The Roundtable will be held at 10:30-11:30 am at Open Doors, 485 Plainfield St., in Providence. There is no open mic, but interested community members might find ways to urge Senator Whitehouse to become even more bold on the Senate floor.