It is difficult, if not impossible, to pursue the goals of punishment at the same time as rehabilitation and reentry.

It is difficult, if not impossible, to pursue the goals of punishment at the same time as rehabilitation and reentry.

Probation is a punishment, and Rhode Island is a national leader in this form of punishment. As noted recently in the Providence Journal, the Governor’s workgroup is looking at ways to amend the state’s practices. Hopefully, any suggestions that pass the legislature or Department of Corrections are substantial and impactful. The crux of this, however, will depend on whether the state has an appetite to reduce punishments and thereby increase rehabilitation and reentry. Keep in mind that some people get sentenced directly to probation while others serve that sentence following a stint in prison.

As a former member and organizer with Direct Action for Rights and Equality (DARE) who has been serving a punishment for 22 years, I can tell you that many Rhode Islanders have been thinking long and hard about this topic, long before anyone could imagine a reduction in punishments for any offense. People are hampered in their attempts to live a productive life because of the crimes we have committed in the past, as there is a natural tendency to exclude us; however, this is reinforced by a probation status that serves to deny jobs, deny homes, deny education, and deny opportunities to help others.

DARE is the only membership-based grassroots organization in Rhode Island with a focus on criminal justice policies. Since forming our Behind the Walls committee in 1998, we are the only policy organization with formerly incarcerated people in leadership, and played a critical role in re-enfranchising people on probation and parole, reducing prison phone rates, ending mandatory minimum sentences, unshackling pregnant women, reducing employment discrimination with Ban the Box, ending probation violations based on dismissed new charges, and (soon) ending blanket discrimination in public housing.

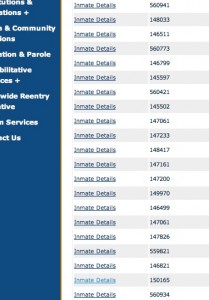

As community members who are overwhelmingly impacted by criminal justice policies, we want to generate stability, support individuals and strengthen our community. Our membership is reflective of the low income communities of color that have the fewest resources to deal with unemployment, homelessness, mental illness, physical health, and substance abuse; i.e. the primary drivers of mass incarceration. Our community members are often both victims and perpetrators of crime, generally excluded from victims’ services once we are convicted. We live this issue, multi-generationally, in a state that has issued over 150,000 prison ID numbers in recent decades.

Ten years ago, DARE took an analytical approach to probation reform in Rhode Island. We knew the stories and lived the lives of people on probation. We recognized patterns of structural discrimination, financial hardship, and mental anguish that make it hard for any normal person to succeed. We recognize that probation is punishment, and the lengthy punishment of our family members, people living in our homes and raising our children, has been a disaster.

DARE articulated a four-point interlocking probation reform platform:

- Limit sentencing on violations to the time remaining on probation (Rule 32(f)). Thus, if one has a single day remaining on a 10-year probation term, they can only be sentenced to a single day. Whereas the status quo is that a judge may instead impose an entire 10-year suspended sentence, we believe this is not only morally flawed but also exceeds (in some cases) the statutory limits on certain crimes.

- Eliminate the 120-day limitation on filing a motion for a sentence reduction (Rule 35). Circumstances rarely change to justify a reduction within four months of the original sentence, yet when someone is serving a ten or fifty year sentence- they will often change over the years. Although the DOC can put some people on low supervision or banked status, their sentence has not ended for any of the structural discrimination purposes such as housing, employment, or volunteering. Nor are they free of the punishment’s mental and spiritual impacts.

- Extend Good Time to people on probation and parole (R.I.G.L. §42-56-24). This adjustment would have several effects, by (a) incentivizing good behavior, (b) naturally shortening sentences, and (c) allow probation officers and/or judges to take away earned Good Time for lower level infractions, similar to ACI discipline boards.

- Allow for violations to be dismissed where the new underlying charge is also dismissed (Rule 32(f)). This proposal passed the legislature after several years of advocacy. It was particularly frustrating when few people believed it was happening, and momentum shifted after Rep. Patrick O’Neill (a criminal defense attorney) interjected during a committee hearing that it is true: sometimes a new allegation comes along and within a few weeks the prosecutor offers a “deal” to plead guilty. If they don’t take the deal, then a maximum sentence on the probation violation is guaranteed. Defendants believe that guarantee, knowing the extremely low standard of guilt, eroded rules of evidence, and notorious cases such as Richard Beverly and Meko Lincoln. Both involved the dubious testimony of police officers ultimately revealed as criminals themselves. Most are “smarter” than Richard and Meko, accepting a few years in prison rather than risk lengthy violations.

These four reforms would reduce the number of people on probation, reduce the number of violations, incentivize good behavior, and allow people a better chance at a second chance.

There is no such thing as a second chance, a fresh start, or anything of the like while on probation. There has long been massive investment in low-income communities, however it has come in the form of police and prisons. Millions of dollars are spent in each neighborhood, although none of that money is an actual local investment. We are not widgets for processing, nor animals for study, nor wetlands to be saved. We are parents, children, brothers, sisters, workers, voters, and even policy experts.

We want a criminal justice system that can protect us without hurting us, where cages are a last resort, where punishments can end, and people can overcome their mistakes. We are the number one stakeholder in reducing overall crime and punishment, and reinvesting resources into affordable housing, jobs, education, along with a health care approach to addiction and mental illness.

I’ve long acknowledged that my sentence will never end, and do not take issue with that. I left Rhode Island to get an education, as my applications were rejected by Brown, URI, RISD, Salve Regina, Providence College, and Roger Williams Law School. Furthermore, several arts organizations, mentorships, and the Training School would not let me volunteer. Regardless of my own saga, Rhode Island needs to look at the systemic issues, and not isolate a few cases. To that end, the Governor would be well served to pick the brains of people who have lived these issues, from cradle to grave.