Seventy years ago, Mrs. Geneva Johnson, a black Montgomery resident, was arrested on a Montgomery, Alabama public transit bus for allegedly having the incorrect bus fare and daring to display improper social decorum by “talking back” to a malicious white bus driver who had berated her. It was not uncommon for bus drivers to abuse and rob black riders at the pay meter. Historian Danielle McGuire notes: “Drivers shortchanged African Americans, then kicked them off the bus if they asked for correct change.”

In the coming years, Montgomery would see the arrest of many more black women — Viola White, Claudette Colvin, Katie Wingfield — and even children who dared to challenge entrenched white power by violating the city’s segregation laws on the public bus lines through their refusal to vacate seating reserved for white passengers. Throughout the nation Blacks (and increasingly their white solidarity partners) were beginning to evince heightened levels of intolerance to, and direct action against, Jim Crow segregation. Their objective was less about the individual indignities of anti-black racism they encountered on Montgomery’s buses, as it was about the imperative to confront systemic white supremacy itself.

In 1952 Montgomery police shot and killed a black man over a fare dispute literally as he exited the bus. In yet another particularly horrid 1953 example, Epsie Worthy refused a white bus driver’s coercive attempt to rob her of an additional transfer fee. “Rather than pay again,” says Jo Ann Gibson Robinson, one of the boycott lead organizers and head of the Montgomery Women’s Political Council (WPC). “[Worthy] decided that she did not have far to go and would walk the rest of the way.” Angered by Worthy’s principled resistance the bus driver leapt from his seat and violently beset upon her. Although she mounted a valiant defense, fearlessly returning counter strikes to the white driver’s rain of fists, she would ultimately suffer a loss this day, which meant jail and a fifty-two dollar fine. After the arrest of eighteen-year-old Mary Louise Smith on October 21, 1955 black Montgomery drew a proverbial line in the sand.

Out of Montgomery’s total black population (which numbered nearly fifty thousand), more than half of all the black women laboring outside of their homes found paid work as domestics in white homes — far beyond the economic safe haven of labor protection laws or a union. Unable to afford private vehicles due in large part to their shamefully low wages, black domestics relied heavily upon the city’s public transportation system. Herein, as a directly affected group, black domestic workers became the all-important foot soldiers of the Montgomery bus boycott. The thoroughly networked social and cultural lives of domestic workers proved to be an invaluable resource for the success of the boycott. As seasoned guerrillas, black women clandestinely transported food, items, and, most critical to the boycott, key information gradually gleaned from white conversations eavesdropped upon.

1950’s Montgomery was home to a significant community of black women, many of whom held professional-class careers as principals, professors, nurses, and social workers. Brown University historian, Dr. Françoise Hamlin, in her multiple award-winning book, Crossroads at Clarksdale: The Black Freedom Struggle in the Mississippi Delta after World War II, remarked on the powerful regional influence of the Montgomery bus boycott: “… black Clarksdale continued efforts in 1956 to apply pressure on the foundations of segregation. The news of the Montgomery bus boycott had spread fast in Mississippi. If change could happen in Alabama, why not Mississippi?”

1950’s Montgomery was home to a significant community of black women, many of whom held professional-class careers as principals, professors, nurses, and social workers. Brown University historian, Dr. Françoise Hamlin, in her multiple award-winning book, Crossroads at Clarksdale: The Black Freedom Struggle in the Mississippi Delta after World War II, remarked on the powerful regional influence of the Montgomery bus boycott: “… black Clarksdale continued efforts in 1956 to apply pressure on the foundations of segregation. The news of the Montgomery bus boycott had spread fast in Mississippi. If change could happen in Alabama, why not Mississippi?”

Charged with getting the boycott off the ground, middle-class women of the WPC were essential to the initial organizational effort of the boycott. However, labor scholar Premilla Nadasen points out that during the 381-day-long boycott the remarkable networking acumen of domestic workers was indispensable:

They filled the pews at mass meetings and served as the foot soldiers that made the boycott a success, and they also exhibited leadership by raising money and mobilizing others in the community to support the campaign.

Black women, like Parks, who labored outside of the home — particularly domestic workers — suffered the compounded indignities of white supremacy on their return trips home. Throughout the day black women often found themselves verbally accosted by white female employers and sexually assaulted by white male employers. Thus, on the bus ride home black women had little tolerance for the inhumane social violence that was part and parcel of a racially segregated seating system. Racist and misogynist epithets like “‘black nigger,’ ‘black bitches,’ ‘heifers,’ ‘whores,’” were humiliating daily occurrences as Robinson remembers.

Rosa Parks was arrested for engaging in a nonviolent direct action against state sponsored white supremacy. Parks clearly was not the first black woman to resist segregated seating, nor was Montgomery’s the first public transit protest by African Americans. The Montgomery bus boycott comes out of a decades-long tradition of black protest against racial injustices in public transit. However, in Park’s case, middle-class black women who formed the core of the Montgomery Women’s Political Council, and had threatened to boycott the buses prior, used Park’s arrest to launch one of the most effective, efficient, and brilliantly orchestrated boycott actions in U.S. protest history. Nevertheless, without the crucial rank and file support of domestic workers Nadasen reminds us that “the bus boycott, quite simply, would never have succeeded.”

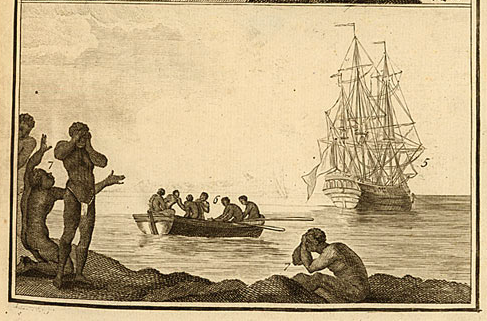

W. E. B. Du Bois, the venerable American historian, sociologist, Pan-Africanist, and first African American to earn a doctorate from Harvard, chronicled Rhode Island’s centralized position as a primary trader in African people in his doctoral dissertation The Suppression of the African Slave Trade.

W. E. B. Du Bois, the venerable American historian, sociologist, Pan-Africanist, and first African American to earn a doctorate from Harvard, chronicled Rhode Island’s centralized position as a primary trader in African people in his doctoral dissertation The Suppression of the African Slave Trade.

In 1935 a crucial piece of worker legislation, the National Labor Relations Act, was passed. Known as the “Wagner Act” after New York Sen. Robert Wagner, who in sponsoring the bill, reasoned that “Men versed in the tenets of freedom become restive when not allowed to be free.” The National Labor Relations Act constituted a seminal democratic moment in American labor and union organizing. Wagner’s bill, among other things, guaranteed protections for union organizing independent of company domination, the right to strike, boycott, and demonstrate against recalcitrant employers, and banned firing as a coercive tool to control union ranks.

In 1935 a crucial piece of worker legislation, the National Labor Relations Act, was passed. Known as the “Wagner Act” after New York Sen. Robert Wagner, who in sponsoring the bill, reasoned that “Men versed in the tenets of freedom become restive when not allowed to be free.” The National Labor Relations Act constituted a seminal democratic moment in American labor and union organizing. Wagner’s bill, among other things, guaranteed protections for union organizing independent of company domination, the right to strike, boycott, and demonstrate against recalcitrant employers, and banned firing as a coercive tool to control union ranks.