June in Rhode Island means two things: ripe strawberries and gubernatorial vetos.

June in Rhode Island means two things: ripe strawberries and gubernatorial vetos.

The silly way our legislature schedules things — with all important bills held until after the budget passes to ensure every legislator falls into line on that vote — means that hundreds of bills are passed in the last few days of the legislative session. This then means they all await the Governor’s signature after the session ends. And some of them get a veto instead.

My favorite veto so far this year was of a bill that would provide a tax break… at someone else’s expense. Sponsored by Representative John McCauley (D-Providence) in the House, and Senators Michael McCaffrey (D-Warwick) and Erin Lynch (D-Warwick) in the Senate, the bill would exempt from the property tax any new construction before it was issued a certificate of occupancy.

The collapse of the housing bubble has meant a real collapse in construction employment. Unemployment among construction workers is almost certainly much higher than the already way-too-high general rate lurking around 11%. It’s natural to think that the industry could use some help. But is it natural to demand that someone else provide it?

Essentially what this bill’s sponsors hoped would happen is to stimulate the construction industry by giving developers a break on property taxes collected by a city or town. One can applaud the motivation while still thinking that the concept is pretty weak.

First of all, it’s not at all clear that this would have a stimulative effect. How many developers are dissuaded from investing by the potential risk of having to pay taxes on property before it’s occupiable? Might not the lack of buyers be a bigger disincentive?

Second, how dare these legislators pile on to the cities and towns? This is a bill that would actually take tax revenue away from many municipalities. Do they not read the news? Are they not aware that we now have three cities in financial trouble, with more on the precipice? In what way exactly would this help those cities?

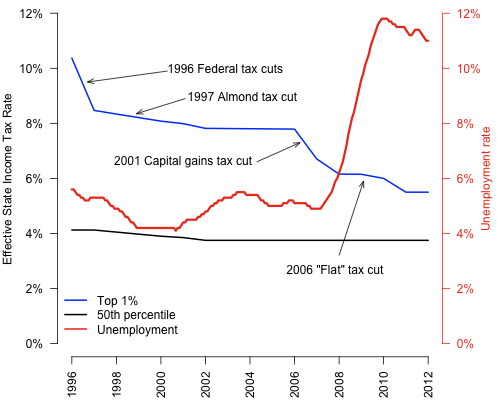

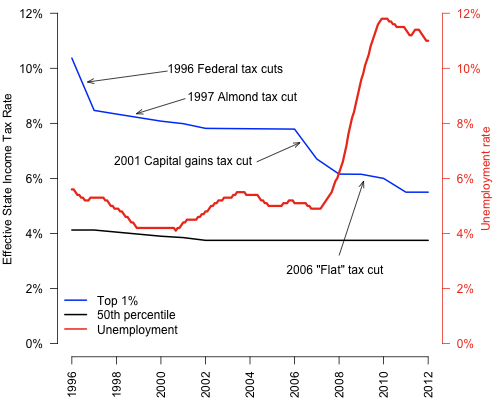

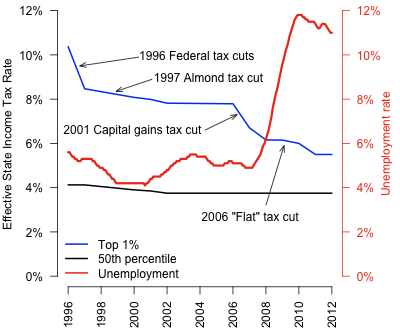

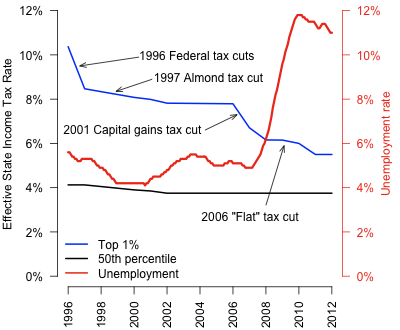

To be honest, this is hardly that unusual. After all, it’s almost traditional in the General Assembly to ignore or hide the cost of tax cuts. I can’t think of a single substantial tax cut over the past 20 years that passed the Assembly with offsetting cuts to services. In fact, the tradition is not only to avoid paying for tax cuts, but to vote to phase them in over several years so the real costs are hidden during the budget year they are debated. This was true of the 1997 income tax cut, the 1997 car-tax cut, the 2006 flat-tax cut, and the 2001 capital gains cut, which didn’t even take effect until five years after it passed.

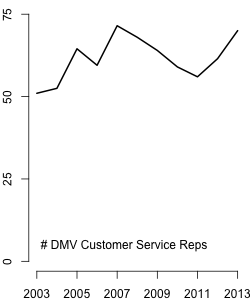

So does this mean unemployed construction workers are out of luck? Probably it does, but not because there is nothing to be done. They are out of luck because the people who can do something choose not to. The General Assembly leadership feels that keeping state revenue down is more important than helping cities and towns. Three years ago municipal budgets across the state were vandalized when the state withheld part of that fiscal year’s state aid payment. Then they did it again the next year, and the next. Between fiscal year 2008 and 2010, the state withheld what amounted to about 10% of Providence’s non-school budget, and millions more for each other municipality.

Admittedly, the state saw its own revenues plunge in 2008, as the income and sales taxes both skidded down in the recession, accelerated by big tax cuts for rich people during each of the years 2007-2011. But the recession and the cuts are over, and revenue in the current fiscal year looks like it will end well ahead of last year’s projections. You might think that would allow us to restore the tax cuts and thereby restore the municipal aid cuts of the previous years, but apparently not. Or you might think we could engage in some small local stimulus, perhaps by accelerating the scheduled repairs of our bridges, maintenance of state buildings, or maybe even re-hiring a few hundred teachers. Nope. Tax cuts are still the only thing on the menu at the state house.

So bravo for Governor Chafee. Bills like this deserve a veto and the legislators behind them deserve to be shamed.