Two Central Falls lawmakers authored a bill that would direct more state funding to libraries in the seven distressed urban cities in Rhode Island. The legislation, which will be heard by a Senate committee today, follows an RI Future investigation last year that showed affluent suburban libraries receive more state library aid per resident than poor urban communities.

“It says right in Rhode Island state law that free public libraries are essential to the general enlightenment of citizens in a democracy and that they are an integral part of the educational system at all levels,” said Central Falls Rep. Shelby Maldonado, the sponsor of the bill in the House. “The law also says that it’s the responsibility of government to provide adequate financial support for all free public libraries. In order for that to be done fairly and effectively, it’s only right that the state should increase library aid to distressed communities to cover their annual assessments to Ocean State Libraries.”

The Central Falls library was shuttered for a time as the city went through bankruptcy. Sen. Betty Crowley, the Senate sponsor of the bill, said only because of a few large, high profile donations does Central Falls have a functioning library. “If it weren’t for people like Viola Davis and Alec Baldwin, they would still be closed,” she said.

In spite of their generosity, the library in Central Falls can’t afford to open on weekends, and closes at 6pm on weekdays. This is an acute issue for Central Falls, said Maldonado.

“A lot of families here still don’t have broad band and don’t even have the internet,” she said. “Our kids don’t have the support they need.”

Crowley said the additional state aid “could enable us to open up on Saturdays.”

The legislation would direct about $500,000 from the general fund to libraries in the seven distressed cities: Providence, $284,423; Pawtucket, $65,124; Woonsocket, $53,107; North Providence, $48,437; West Warwick, $40,321 and Central Falls, $18,566. The amounts are based on the contribution each community makes to the Ocean State Library consortium, the umbrella organization for local libraries in Rhode Island.

The new revenue would come from the general fund, Maldonado said, and thus wouldn’t affect state library funding in other communities. “Leadership is open to the idea and we continue to have ongoing conversations,” she said.

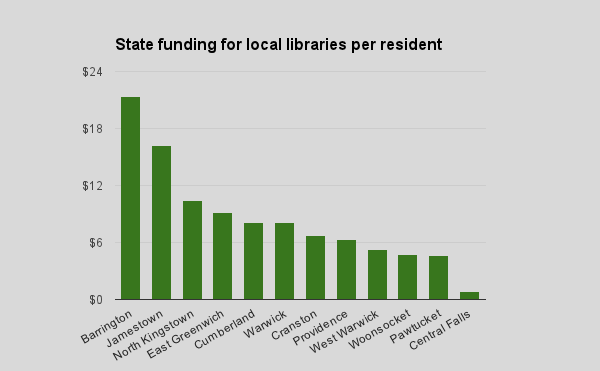

Rhode Island’s state library funding formula matches city and town investment, a regressive method that rewards affluence and punishes poverty. Last year the state gave $337,167 in library aid to Barrington and $26,046 to Central Falls.

An RI Future investigation last year showed per resident Rhode Island gives the most library aid to: Barrington, Jamestown, North Kingstown, East Greenwich and Cumberland. The communities to get the least state library aid per resident were: Central Falls, Pawtucket, Woonsocket, West Warwick and Providence.

Deborah Barchi, director of the Barrington library and a past president of the Ocean State Libraries consortium, told RI Future last year she thinks the state funding formula for local libraries is fair. “Each town makes those decisions based on what they value,” she said. “No matter what metric you use, there would be somebody who would feel they weren’t getting enough money.”

But Steve Larrick, the Central Falls planning director and a member of the city library’s board of directors disagreed.

“We think the state needs to play a role in our urban libraries,” he said at the time. “Barrington doesn’t need a library to have access to tremendous resources,” he said. “They have great access to broadband in their homes, and their schools are top notch. Their school library is probably better than our public library. A dollar spent there will not be as meaningful as a dollar spent on the Central Falls library.”

Even the very conservative Center for Freedom and Prosperity, in its spotlight on spending report last year, agreed the state library aid formula is highly regressive.

“It isn’t often that we get to agree with our progressive friends on a matter of government spending, but RIFuture editor Bob Plain noticed that the state gives extra library aid to some communities because they’re able to invest more in their own facilities,” according to its report. “Consequently, Barrington receives over $20 per resident to subsidize its gem of a library while urban residents receive less than $10.”

The Senate Finance Committee will consider the bill today after the full Senate convenes.