The ongoing discussion of eliminating the sales tax proves the enduring value of telling people what they want to hear.

The ongoing discussion of eliminating the sales tax proves the enduring value of telling people what they want to hear.

Don Carcieri, for his whole term, told people that government could be cheaper, but really all he did was insist it be so and ignore the evidence when it turned out not to work quite the way he’d hoped. Does anyone remember the “big audit”? It was done early in his administration, but all the findings about places where increased investment would help our state were deep-sixed and the other results were insignificant enough that the whole project was considered a minor embarrassment and mostly forgotten.

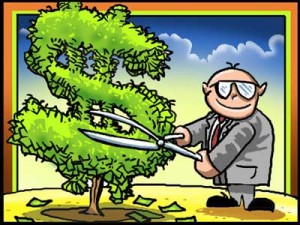

The most recent success along these lines is the RI Center for Freedom, Prosperity, Motherhood, and Apple Pie who have enjoyed an astonishing level of success in keeping under discussion their claim that Rhode Island would profit by eliminating or slashing its sales tax. There’s a legislative commission that keeps meeting and they put out an unending stream of press releases that occasionally get reprinted.

So here I am, feeding into exactly that need for attention they crave, but let’s be clear: this is a stupid idea, supported by fantasy projections and a misunderstanding of the real world.

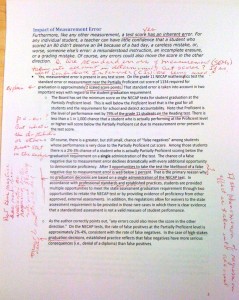

I see from their most recent press release that they claim a reduction of the sales tax to 3% would produce secondary effects worth much more than the revenue lost: over 13,000 new jobs, hundreds of millions in new revenue to the state and cities and towns, and so on. They call these “dynamic projections” presumably because everyone knows that something that is “dynamic” must be good. They do say that state revenue might be down by a bit, but made up by city and town revenue. (An aside is important here: we often see claims like theirs that Rhode Island’s sales tax is the highest in the country. This is false, or misleading at best. In most states, county governments are supported by sales taxes, and there are places in 31 states — including Texas, Arizona, and most of the South — with a higher sales tax than ours.)

But let’s look at these “results” of theirs. They claim, for example, that their model predicts $79 million in new sales tax revenue. This is a 20% boost in sales. Do you believe that lowering the cost of a $100 item from $107 to $103 will produce a 20% increase in sales of that item? That is, they predict that a 3.7% savings will produce a 20% increase in sales. Do people out there with retail experience think this is remotely likely? Presumably people will spend a little more when there are savings, but seriously? Perhaps they imagine hordes of Swansea residents will drive through Seekonk to do their shopping in Warwick in order to save a few percent on their purchases?

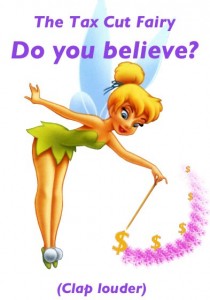

The CFPMAP report goes on to imagine that the resulting 20% increase in retail sales in Rhode Island will be responsible for $208 million in income tax revenue. Backing this out, that means they imagine the 20% increase in sales will be responsible for around $4 billion in income for the state. This is almost a 10% increase in the economic output of the entire state. Do you believe this will be the result of a sales tax cut? They are only (only!) projecting an increase in taxable retail sales of $2.5 billion, so the other money presumably comes from the tax cut fairy. The 13,000 new jobs they suggest would appear don’t even account for a quarter of the increase in income they project. The rest is because everyone else would get a raise, or more hours. Would you expect a raise if the sales tax is cut?

One could go on, into their hidden assumption that all these new hires and raises happen instantaneously upon the announcement of the newly lowered tax, or into their projections that newly-prosperous Rhode Islanders would buy 32% more cigarettes and 25% more liquor (also immediately), thereby swelling the revenues from those taxes, but why bother? The proposal is ridiculous, supported by projections that will take in only the gullible and those who really wish to be taken in.

And there’s the issue, really. Lincoln Almond and Don Carcieri owe their success to the desire of people to believe their claims that government could be cheaper. They were not brave politicians, taking on the fearful power of special interests. They were guys who were propelled into high position by promising people what they wanted to hear and maintaining that it was possible long after events had proven them wrong. Theirs was no kind of courage. Political courage is what we have seen in Governor Chafee, who has consistently presented us with tax and budget proposals that worked against his interest in re-election — and that have been consistently overridden by legislative leaders more interested in theirs. Let us only hope that they are able and willing to see through this latest sales tax claptrap.