SUMMARY

SUMMARY

The shift away from group homes for the developmentally disabled toward care based on shared living arrangements (SLA) is a national trend driven by economic and demographic forces. While it is widely recognized that “shared living is not for everyone,” states have different views regarding when this option is and is not appropriate. I argue that SLA-based care should be recognized as inappropriate for individuals whose ability to communicate is below the level of an average six-year-old child.

Introduction

“Shared living is not for everyone” – writes Robin E. Cooper of the National Association of State Directors of Developmental Disabilities Services.1 Having said that, she gives no explicit guidance regarding who shared living is not for. However, she does add that shared living must be “freely chosen.” Indeed, this follows from her definition of shared living as “an arrangement in which an individual, a couple or a family in the community and a person with a disability choose to live together and share life’s experiences” (italics in original).

So one guideline is implicit in her definition. Shared living is for people whose level of intellectual development enables them to make a free and informed choice. Conversely, it is not for people whose level of intellectual development is too low for them to be capable of making such a choice. In this paper I argue in favor of adopting this guideline explicitly.

The arrangements under discussion are named differently in different states. Most names are variants on either “adult foster care” or “shared living” (or “life-sharing”). The official term in Rhode Island is “shared living arrangements” (SLA). “Shared living” does convey an important aspect of these arrangements, but another aspect is no less important—care and support of the disabled person. It is not simply a matter of sharing accommodation. This second aspect is the focus of another definition that we find in an official report of the State of Vermont:

Shared living is a method of providing individualized home support for one or two adults and/or children in the home of a contracted home provider. Home providers typically have 24 hour a day/7 days a week responsibility for the individuals who live with them.2

This is why I have settled on the dual term “SLA-based care” (or “life-sharing care”).

A national trend

Study of the websites of various state governments confirms that the shift from group homes toward SLA-based care is a national trend. According to Robin Cooper, the trend is driven by “economic and demographic forces”—specifically, the recession, growing waiting lists, staff shortages, and the increasing cost of shift-staff residential programs. As increased pay and improved benefits would almost certainly eliminate staff shortages, what this all comes down to is money. Budget allocations are falling further and further below what would be required to sustain past levels of provision of places in group homes.

The difference in cost between the two types of provision is large. According to Charles Williams, head of the Developmental Disabilities Division in Rhode Island’s Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities, and Hospitals (BHDDH), state aid to group housing is 50 percent higher than state aid to shared living.3 The Vermont Report gives a much wider difference in average annual cost ($29,018 for shared living, $83,372 for group homes in 2009).

Although the NASDDDS Report attributes the trend wholly to economic and demographic factors, others have given philosophical justifications of the shift toward SLA-based care. They claim that it integrates clients more closely into the community and therefore constitutes a new stage in the process of de-institutionalization. Whether such arguments would carry weight in the absence of financial pressure is another matter.

Choice?

If the trend toward SLA-based care is driven by financial pressure, then what role is played by the element of “choice” that Robin Cooper emphasizes in her definition? No source that I have yet seen cites any data on “consumer preferences” – that is, wishes expressed by clients and their families as recorded in case files or collected by means of special surveys. People with long experience of work in group homes say that residents become attached to the places where they are (they come to feel “at home” there) and are reluctant to move. Are the extent – and especially the pace – of change required by financial targets embodied in state budgets compatible with a genuine process of free and informed choice?

Choice should apply not only to the initiation of a life-sharing arrangement but also to its termination. The State of Georgia has a guidance document on SLA-based care that includes a clause entitled “Individual Choice to Terminate Relationship” and mandating interviews conducted “by a neutral party to determine that the individual’s choice is independent of coercion from any party.”4 This is all well and good as far as it goes (provided that the individual has the requisite ability to communicate). However, what choice does the individual have concerning where to go next if the group home from which she or he came is now closed? There may be choice between one life-sharing provider and another but little or no choice regarding the SLA option itself.

Advantages and disadvantages of SLA-based care

One useful feature of the Vermont Report is its lists of advantages and disadvantages of SLA-based care, which I reproduce as an appendix.

The advantages outnumber the disadvantages 10 to 6, but from the point of view of the welfare of the disabled person this is a little misleading. Three of the advantages accrue not to the disabled individual but to the provider (nos. 2 and 4) or the state (no. 3). The remaining advantages then only slightly outnumber the disadvantages.

Note also that most of the advantages (Nos. 5—10) are about good things that may happen in a very successful life-sharing relationship, while the disadvantages refer mainly to the consequences if for any reason the relationship does not work out well. Thus, if the relationship turns sour it is the disabled person who has to move out and lose his or her home. A similar situation in a group home may be resolved by the departure of someone else.

I attach special importance to Disadvantage 3 – the greater difficulty of effective oversight in SLA-based care. In a group home other people are always around to observe and report any instances of abuse or neglect – people who are not related and therefore less inclined to cover up for one another.

Some advantages and disadvantages “cancel out”: shared living may give the disabled person more extensive contacts than those ordinarily provided by group homes (Advantages 5, 6, and 9). However, if the host family itself is socially or physically isolated (many live in rural areas), then living with them may restrict contacts and leave the person even more isolated than in a group home (Disadvantages 2 and 5).

To sum up, SLA opens up a wider range of possible outcomes than group homes. At best it makes possible a kind of loving family care that a group home can never provide. At worst, however, it entails a greater risk of undetected neglect and abuse than in the group home setting. This suggests a general guideline: those for whom SLA-based care is inappropriate are those most at risk of such an outcome.

What if anything do SLA-based and child foster care have in common?

Child foster care has been marred by many failures and abuses and has acquired a poor public reputation. An important reason why many people avoid use of the term “adult foster care” is to prevent people from associating SLA-based care of the disabled with “disreputable” child foster care. They argue that it is unfair to associate the two because children placed in foster care tend to come from broken or abusive homes and consequently have severe emotional problems with which many foster parents fail to cope. This factor does not usually apply to the disabled.

This argument has considerable weight. However, it does not follow that SLA-based care and child foster care have nothing significant in common. People with developmental disabilities, especially of a severe kind, do resemble children in important ways, and children can be difficult to look after even when they do not come from broken or abusive homes.

Some SLA providers, like some foster parents, neglect the individuals entrusted to their care for reasons that have nothing to do with the problems of those individuals. In both cases money may play too prominent a role in the motivation for providing care, and providers may display a pattern of behavior (not necessarily conscious) that favors their natural children over the person in their care.

For example, a television program highlighted a case in Pennsylvania about a developmentally disabled young woman in SLA-based care who was being abused by the young sons of her providers. Although they were quite heavy they would “playfully” jump on her and constantly demand piggyback rides from her, which gave her backache. There was no one to come to her aid while this was going on: the boys’ father was out and their mother was locked in the study at work on the computer. She could have been similarly neglected had she been a few years younger and placed in child foster care. It would not have made much of a difference.

For whom is SLA-based care inappropriate?

Apparently no one denies the existence of certain types of disabled people for whom SLA-based care is inappropriate. It is recognized that a host family cannot provide adequate care to a disabled person with complex medical needs requiring immediate access to medical professionals and advanced equipment. Nor can members of a host family be expected to exhaust and endanger themselves by attempting to cope with the most extreme forms of dysfunctional behavior.

There are, however, divergent views over where exactly the line should be drawn. Some states consider SLA-based care appropriate across the spectrum of needs, excluding only the groups mentioned in the previous paragraph but including other people with severe developmental/intellectual and/or physical disabilities. It appears to me that Rhode Island is one of these states, although I shall be very happy to be proven wrong.

Other states also exclude people with severe disabilities. South Dakota is one state that considers “Adult Foster Care” (that is what they call it in South Dakota) appropriate only for people with relatively mild disabilities. To quote their website:

The primary function of an Adult Foster Care home is to provide general supervision and personal care services for individuals who require minimal assistance in activities of daily living (ADLs), who require supervision/monitoring with the self-administration of medications, and who require supervision/monitoring of self-treatment of physical disorder. Activities of daily living are defined as any activity normally done in daily life which includes sleeping, dressing, bathing, eating, brushing teeth, combing hair, etc. …

Individuals between the ages of 18 and 59 who are capable of self-preservation in emergency situations and need supervision or monitoring in one of the following areas: 1) the activities of daily living; 2) the self-administration of medications; or 3) the self-treatment of a physical disorder.5

Thus in South Dakota individuals who require more than “minimal” assistance in activities of daily living, who cannot administer their own medication or treat their own physical disorders even with supervision and monitoring, or who would be unable to save themselves in an emergency are not considered suitable for SLA-based care.

Ability to communicate as a key criterion

Without denying the relevance of the criteria used by South Dakota, I argue that a key criterion should be ability to communicate. This is because it is especially important to exclude from SLA-based care those whose disabilities make it impossible for them to report any abuse or neglect that they may suffer and also to exercise their hypothetical right to choose whether to initiate or terminate a life-sharing relationship.

Let’s revisit Georgia’s exemplary clause on “individual choice to terminate relationship” and try to apply it to a physical adult who in mental terms remains a toddler, either completely non-verbal or with a vocabulary of a dozen or so words. “When an individual indicates a desire to terminate services from a Host Home provider” (how? by running away?) “the individual will be interviewed by a neutral party” (but he or she doesn’t know how to answer questions). “The individual’s support coordinator … will interview the individual’s legal guardian (if any) and/or any representative who has been formally or informally designated by the individual” (but the individual is incapable of designating a representative, even informally).

Some may say that it suffices if the right to choose is exercised on the individual’s behalf by a guardian. Guardians who as parents or other close relatives used to care for the individual and who visit the individual frequently are indeed the best persons to detect signs of any abuse that may have occurred and to take decisions on the individual’s behalf. However, when communication deficits are very severe even parents may be unable to assess a situation reliably. For instance, it is hard even for them to judge whether unresponsiveness and withdrawal result from distressing experience or lack of interaction (a form of neglect) or whether they have some harmless cause. Moreover, when the original guardians lose the ability to perform the duties of guardianship or die the new guardian may be a relative who is unable to visit so frequently or – even worse – some court-appointed lawyer who does not know or care very much about the individual and hardly ever visits. Or there may be no guardian at all: the disabled person may become a ward of the state.

How is ability to communicate to be measured? A common measure of general intellectual ability for the developmentally disabled is mental age. Ability to communicate usually but not always corresponds to mental age. Some people’s ability to communicate is impaired solely by physical disabilities (or perhaps they could communicate adequately, but only with the aid of advanced equipment that is too expensive or not yet widely available). Autism also impairs communication. So mental age is not quite what we need. We need not the individual’s mental age but the mental age that corresponds to the individual’s ability to communicate – that is, the average age of children without disabilities whose ability to communicate is at the same level as that of the individual. We could call this the individual’s “communicative age.”

Below what limit in terms of communicative age should we recognize an individual as especially vulnerable and therefore unsuitable for SLA-based care?

According to the Encyclopedia of Mental Disorders, the “mentally retarded” (in deference to the current demands of political correctness I shall switch that to “developmentally disabled”) are a class of individuals with IQ below 70 and mental age below 12 years. They make up about 2% of the population and are divided into four subgroups on the basis of degree of disability: mild, moderate, severe, and profound. The mildly disabled, with IQ in the range 50—69 and mental age in the range 8—11 years, account for 85% of the whole class. The moderately disabled, with IQ in the range 35—49 and mental age in the range 4—7 years, contribute another 10%. The severely and profoundly disabled, with IQ below 35 and mental age below 4, make up the remaining 5%.

I suggest that we set the limit in such a way as to recognize as unsuitable for SLA-based care all the severely and profoundly disabled and a section of the moderately disabled – that is, individuals with a mental (more precisely, communicative) age below 6 years. This would cover somewhat less than 10% of the whole class (perhaps 8%), because people with a mental age of 6—7 outnumber people with a mental age of 4—5.

Who would assess an individual’s communicative age? I suggest that the parents (or other family caregivers) and the caregivers at the day program attended by the individual (if any) be asked to estimate his or her communicative age. If both give ages below 6 years that would decide the matter in one direction; if both give ages of 6 years or above that would decide the matter in the other direction. Only if one assessment is below 6 years and the other is 6 years or above would the matter be referred for a professional assessment.6

Do we need formal criteria?

Some people prefer not to classify the developmentally disabled on the basis of formal criteria, especially if these criteria focus on degree of disability. They say that they prefer to treat people as individuals.

This sounds very nice. Formal rules do have their drawbacks. They often fail to make provision for exceptional cases. But in the real world they are a lesser evil. A lack of formal rules can easily result in – and help cover up – a financially driven neglect of vital needs.

People have unique individual needs. But they also have needs that they share with other members of a certain class. For example, blind children need to be taught braille and deaf children need teachers able to converse with them in sign language. If they were not classified as blind or deaf but regarded only as unique individuals with a right to be placed in “the least restricted environment” then those needs would probably go unmet.

In the same way, people with severe developmental disabilities have special needs for care and protection that they share with one another but do not fully share even with people fortunate enough to have only mild developmental disabilities. Due attention to these class-specific needs is quite compatible with efforts to meet their individual needs as well – to provide each individual with his or her favorite toys, stuffed and squeaky animals, games, foods, videos, songs, and other sensory experiences.

If decisions about which needs to meet and how to meet them were made solely by competent professionals concerned only with the welfare of their charges, then we might just leave things to them and not burden them with formal rules.

Unfortunately that is not the situation. Financial pressure is a powerful influence on decision making. In the absence of formal criteria that pressure may inflict special harm on the severely disabled because it is their care that involves the highest per capita costs. It may well seem to decision makers concerned primarily with costs that this is where the biggest savings are to be made.

To be specific, unless people with severe developmental disabilities are explicitly deemed unsuitable for SLA-based care the financial pressure to place them in such care will be even stronger than the pressure to place the mildly disabled there. As Mr. Williams informed the Warwick Beacon: “On average the annual savings for an individual in SLA over group housing is $19,400, with that number increasing depending on the severity and dependence on services” (my italics).7

So yes, we do need formal criteria. Compliance with formal criteria can be verified. That makes it possible for us to hold our state officials accountable. If we could have implicit trust in them we would not need formal criteria. But we cannot trust them. In fact, it is our civic duty to distrust them. The principle of organized distrust of government lies at the core of American constitutional thought. That is its main contribution to the progress of civilization.

Notes

1. In a report entitled Shared Living: A New Take on an Old Idea, prepared for the Arizona Developmental Disabilities Planning Council and issued in Spring 2013 (henceforth “the NASDDDS Report”). Available for download at the site of the NASDDDS. If you have trouble downloading it (as I did) e-mail me at sshenfield@verizon.net and I’ll send it to you.

2. Shared Living in Vermont: Individualized Home Supports for People with Developmental Disabilities 2010. State of Vermont, Division of Disability and Aging Services, Department of Disability, Aging and Independent Living (henceforth “the Vermont Report”). Accessible at www.dail.vermont.gov. The inclusion of disabled children as well as adults here confuses the distinction between shared living and foster care.

3. Daily rates of $162 versus $109. See: Kelcy Dolan, “Budget concerns shift perspective from group homes to shared living,” Warwick Beacon, January 21, 2016 (http://warwickonline.com/stories/budget-concerns-shift-perspective-from-group-homes-to-shared-living,108733).

4. Process for Enrolling, Matching, and Monitoring Host Home/Life-Sharing Sites for DBHDD Developmental Disabilities Community Service Providers, 02-704, Clause F (https://gadbhdd.policystat.com/policy/832301/latest/).

5. State of South Dakota, Department of Human Services, Division of Developmental Disabilities, page on Adult Foster Care (https://dhs.sd.gov/dd/adultfc.aspx).

6. The assessment could be carried out at the Children’s Neurodevelopment Center (formerly the Child Development Center) at Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence – if they agree to count developmentally disabled adults as “children”!

7. Source as for note 3.

Appendix. Advantages and disadvantages of shared living according to the Vermont Report

Advantages

1. Shared living offers a wide variety of flexible options to meet the specific needs of individuals.

2. The “difficulty of care” payment to a home provider is exempt from federal and state income tax.

3. Shared living, on average, has a lower per diem cost than other types of twenty-four hour a day home support, such as staffed living and group homes.

4. Shared living offers an opportunity for support workers to earn income while working out of their home.

5. Home providers may support and facilitate contact with the individual’s natural family.

6. A home provider’s extended family and friends often become the “family” and friends of the individual who lives with them. The individual may have a chance to share holidays and go on vacations with the home provider.

7. Consistency in supports offered in a home setting is good for individuals who are highly medically involved or have other complex support needs. There is a high probability that individuals in shared living who are terminally ill will receive end of life care at home.

8. Shared living often leads to long-term stability and consistency in the individual’s life as many home providers become life-long companions to the individual who lives with them.

9. Home providers often provide the necessary transportation that helps an individual get to places he or she needs or wants to go.

10. Shared living offers targeted skill development that affords a safe and measured approach toward more independent living

Disadvantages

1. Individuals receiving services from agencies may become comfortable with this option. It can therefore be programmatically, emotionally and fiscally challenging for individuals to “graduate” out of shared living to more independent supervised living.

2. Shared living can limit an individual’s exposure to other people and places outside the home or to what the home provider experiences.

3. There may be fewer independent or external eyes on the individual, thus reducing opportunities for oversight.

4. Because the home must be the primary residence of the home provider, if the specific living arrangement does not work it is the individual that has to move out.

5. Given limited public transportation and the rural location of many shared living homes, an individual’s access to alternative transportation options are often limited.

6. Home providers may be challenged when, as employers, they are required to hire, train and supervise workers to provide respite, community supports and/or employment supports to the individual living with them.

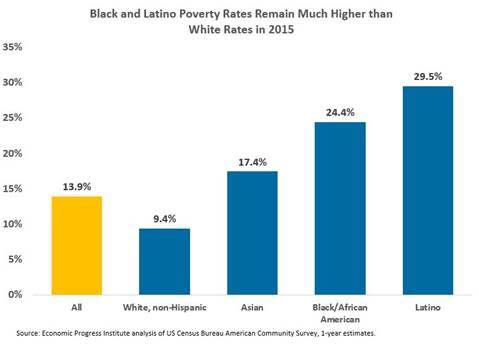

Over one hundred forty thousand (141,035) Rhode Islanders lived in poverty in 2015, according to new data released today from the Census Bureau. The drop in the rate to 13.9% in 2015 from 14.1% in 2014 is not statistically significant. The poverty level for a family of four is approximately $24,000.

Over one hundred forty thousand (141,035) Rhode Islanders lived in poverty in 2015, according to new data released today from the Census Bureau. The drop in the rate to 13.9% in 2015 from 14.1% in 2014 is not statistically significant. The poverty level for a family of four is approximately $24,000.

Rosa was waiting near the end of a line of about 30 people when I found her at 8:30am in the Kennedy Plaza terminal building Wednesday morning. In her hand she held a senior/disabled bus pass that was due to expire in September 2020, but a driver told her that the pass was no good anymore and that she had to get a new bus pass if she wanted to continue to ride at the reduced fare.

Rosa was waiting near the end of a line of about 30 people when I found her at 8:30am in the Kennedy Plaza terminal building Wednesday morning. In her hand she held a senior/disabled bus pass that was due to expire in September 2020, but a driver told her that the pass was no good anymore and that she had to get a new bus pass if she wanted to continue to ride at the reduced fare. Further up the line Frederick, a disabled man in his late thirties, told me that he had waited in line for over two hours the day before. “They cut off the line at ten people, and told the rest of us to come back tomorrow,” he said. He added that it is difficult for him to get around without a bus pass.

Further up the line Frederick, a disabled man in his late thirties, told me that he had waited in line for over two hours the day before. “They cut off the line at ten people, and told the rest of us to come back tomorrow,” he said. He added that it is difficult for him to get around without a bus pass. “There was no way to determine if a pass holder had died or moved away; their passes remained active and in use in our system until they expired. So we knew we needed to lessen the time the passes are valid. They will now be valid for two years, not five. The passes being issued now will expire on a customer’s birthday after the two-year mark, so everyone will not have to re-qualify at the same time again – it will be staggered.”

“There was no way to determine if a pass holder had died or moved away; their passes remained active and in use in our system until they expired. So we knew we needed to lessen the time the passes are valid. They will now be valid for two years, not five. The passes being issued now will expire on a customer’s birthday after the two-year mark, so everyone will not have to re-qualify at the same time again – it will be staggered.”

Social services for the blind and visually impaired are among the hardest hit as a result of the new computer system at the state Department of Human Services, said Rui Cabral, board member of the

Social services for the blind and visually impaired are among the hardest hit as a result of the new computer system at the state Department of Human Services, said Rui Cabral, board member of the

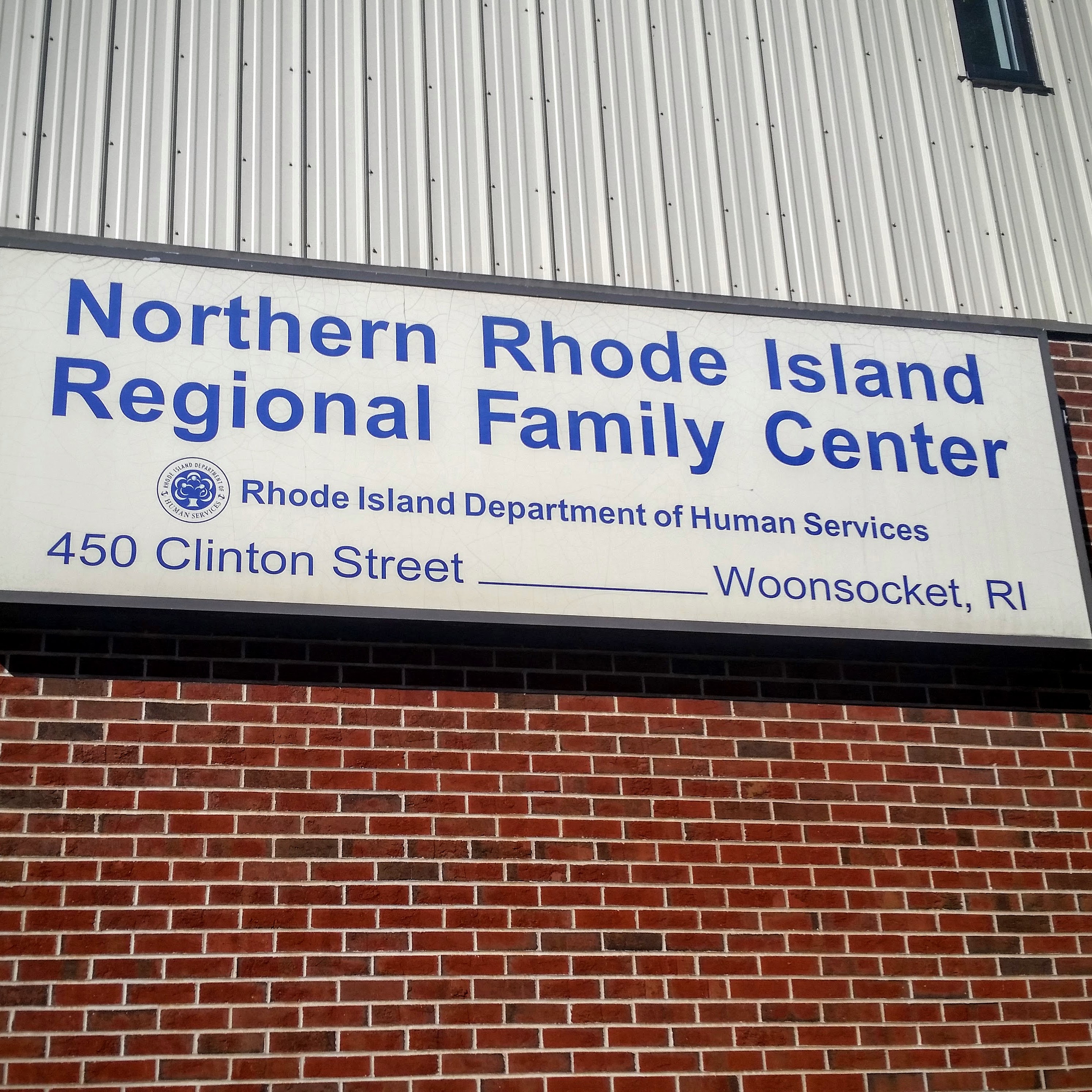

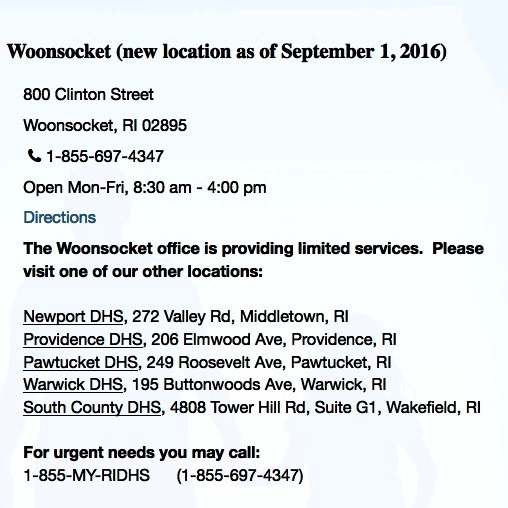

People in need of social services are being turn away from the Woonsocket branch of the RI Department of Human Services (DHS) as the offices are in the midst of a downsizing and relocation.

People in need of social services are being turn away from the Woonsocket branch of the RI Department of Human Services (DHS) as the offices are in the midst of a downsizing and relocation.

The clients DHS serve are among the most vulnerable in the state, who often have difficulty with transportation and access to the internet. Closing offices, downsizing staff and limiting services, even if only for a month, could have catastrophic effects on families.

The clients DHS serve are among the most vulnerable in the state, who often have difficulty with transportation and access to the internet. Closing offices, downsizing staff and limiting services, even if only for a month, could have catastrophic effects on families.

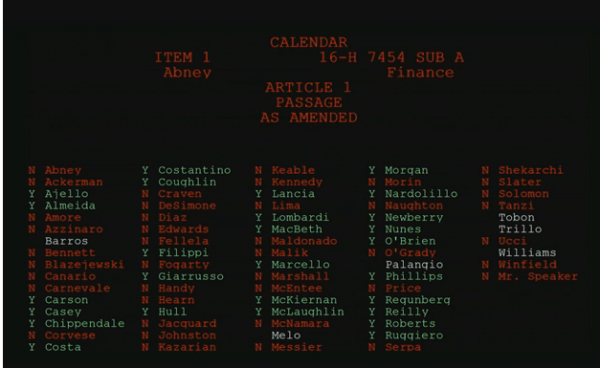

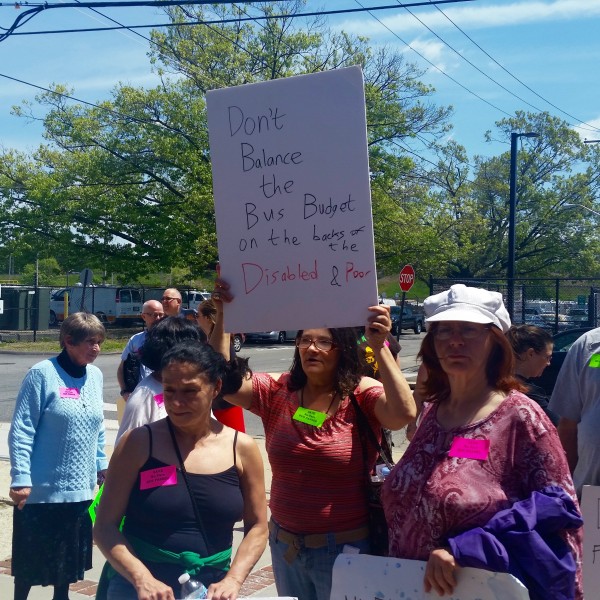

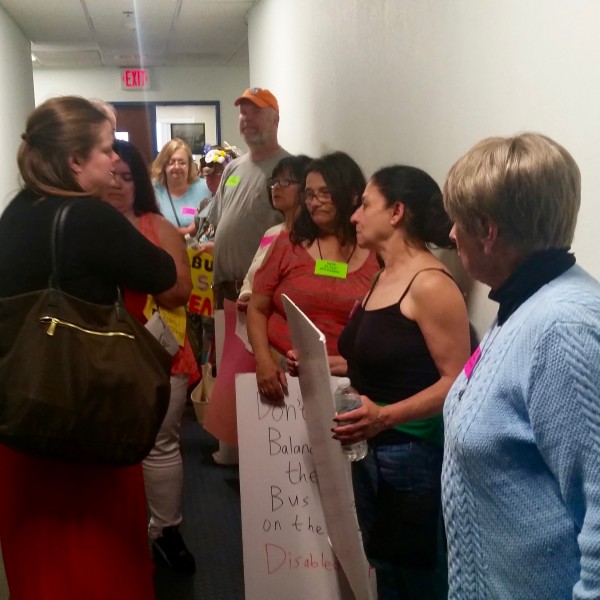

Some of Rhode Island’s most vulnerable people were dealt a serious blow in the recently released House budget. Disabled and senior Rhode Islanders are going to be hit with a bus fare hike now expected to start in January.

Some of Rhode Island’s most vulnerable people were dealt a serious blow in the recently released House budget. Disabled and senior Rhode Islanders are going to be hit with a bus fare hike now expected to start in January.

Red Bandana Award winner Artermis Moonhawk lead a group of homeless, elderly and disabled people and allies carrying signs demanding that RIPTA re-institute the

Red Bandana Award winner Artermis Moonhawk lead a group of homeless, elderly and disabled people and allies carrying signs demanding that RIPTA re-institute the

SUMMARY

SUMMARY