How rare of a marine mammal sighting are the beluga whales that have been spotted at various locations in Narragansett Bay on Sunday and Monday?

“It’s the second one ever in Rhode Island,” said Bob Kenney, an oceanography professor at the URI Bay Campus who studies whales and wrote this about belugas.

“The first one was last year,” he added.

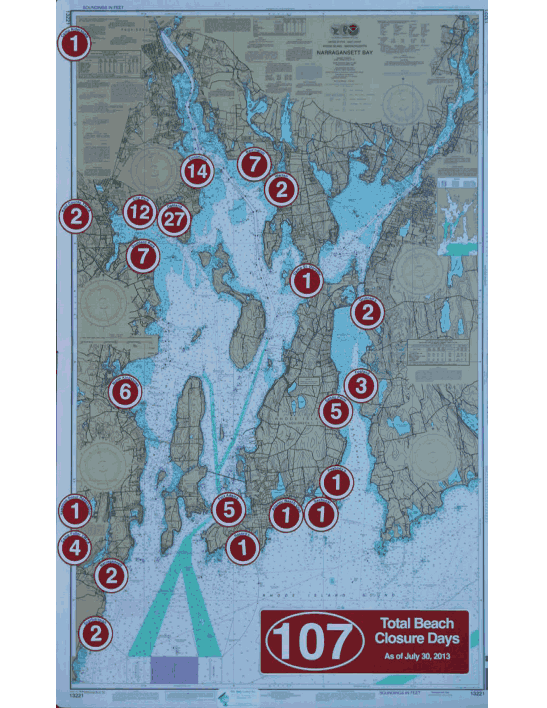

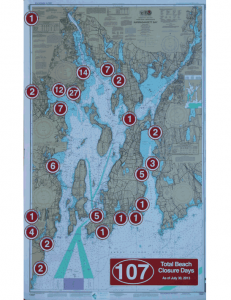

In July, 2014, a fisherman spotted and videoed a lone beluga whale in the West Passage between Jamestown and Saunderstown. At roughly the same time, a second beluga whale was seen in the Taunton River near Fall River last year.

Then on Sunday, David DeSalvo and Matt King videoed three beluga whales north of the Newport Bridge and just off the eastern shore of Jamestown. DeSalvo estimated they were about 12 to 15 feet long.

On Monday morning, the RI Department of Environmental Management fielded reports that the three beluga whales were seen further north up Narragansett Bay off Rocky Point in Warwick. A team from DEM and Mystic Aquarium dispatched a 22-ft research boat, crewed by two biologists and a veterinarian, to ensure the mammals are healthy on Monday. They appeared healthy in the video, said April Valliere, a supervising biologist who studies marine mammals with DEM.

She said increasingly colder waters in southern New England may be enticing beluga whales from their native habitat of the St. Lawrence Seaway in northeastern North America.

“I suspect cooler water temperatures have something to do with it,” she told me. “It’s off several degrees. It’s still in the 40’s outside the Bay.”

But she said scientists really don’t know yet. “We’re not really sure. Obviously there is food for them,” she said, noting that squid and menhaden are now running in Narragansett Bay.

There’s a theory that the heavily-polluted St. Lawrence may be causing cancer in beluga whales. Perhaps the pearl white whales are relocating to a cleaner habitat? In a Providence Journal op/ed last year, Mystic Aquarium President Steven Coan said a changing climate is opening up new southern habitat to beluga whales. “The sight of a Beluga in southern New England is rare and unusual today but could quickly become a more frequent occurrence. Climate change is affecting our seas and the creatures that live in them. In some cases the natural food supply for a certain species may shift location, moving to a warmer or cooler spot in the ocean.

Beluga whales aren’t the only whales that visit Narragansett Bay. Minkie whales frequent the lower Bay as does the occasional fin whale in the winter. Several species of whales live in or pass through the Rhode Island and Block Island sounds, the parts of the Atlantic off the coast of Rhode Island.

Whales are protected by the Marine Mammal Protection Act, and as such it’s a felony to disturb them. Boaters, Kenney and Valliere both stressed, should take extreme caution.

“Anything a boater does that disturbs teir natural behaviors is a violation of federal law, you could go to jail for up to two years” Kenney said. “The best thing to do is shut the engine down and watch them. They may just come close. But don’t chase them.”

But he doesn’t look for lobster traps anymore. Now he uses the Newshell to service his oyster farm just south of the Jamestown Bridge.

But he doesn’t look for lobster traps anymore. Now he uses the Newshell to service his oyster farm just south of the Jamestown Bridge.

Paterson and Goerner were attaching to the 4,000 pound anchor this underwater lift bag –

Paterson and Goerner were attaching to the 4,000 pound anchor this underwater lift bag –

Thank someone like this:

Thank someone like this: